A sustained and increased wealth gap

The nation’s racial income and wealth gap increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the seven-county region was not an exception to the racial disparities that deepened nationally. In 2022, per capita income of Black people in the region ranked second worse among the 25 largest metro areas.17

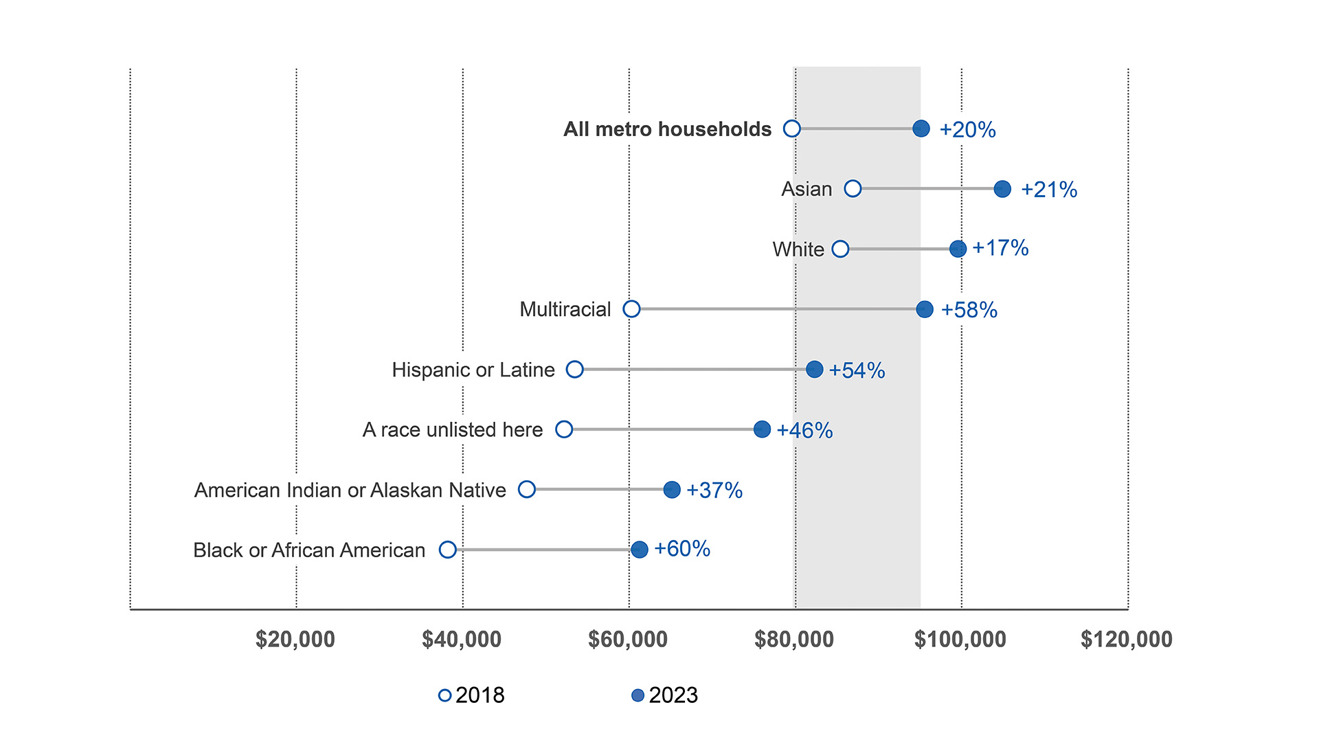

Despite recent gains, median income for Black, American Indian, and other households of color lag behind other groups

Between 2018 and 2023, the median household income in the region grew over $15,00018 but disparities in wealth remain. Even with growing incomes and increased net wealth for households of all racial groups in the region, the net wealth gaps between Black, American Indian, and other households of color compared to white households increased.19 These increases in net wealth gaps indicate that while income has increased across racial and income groups, economic benefits are not being evenly distributed across households of different races and ethnicities. Higher income and white households are getting wealthier, and more people of color and low-income households continue to be left behind. The COVID-19 pandemic and other economic events have exacerbated these impacts, leaving these households at risk of housing instability.

In addition to income disparities by race, the seven-county region has some of the largest racial wealth gaps in the United States. Building wealth is a crucial factor in promoting generational economic mobility and providing families with housing security. Greater household wealth means more access to resources to pay for higher education, start a business, purchase a home, and cover emergency expenses. In 2021, the median net worth, excluding home equity, of a white household was $104,400 compared to $8,320 for a Black household.20

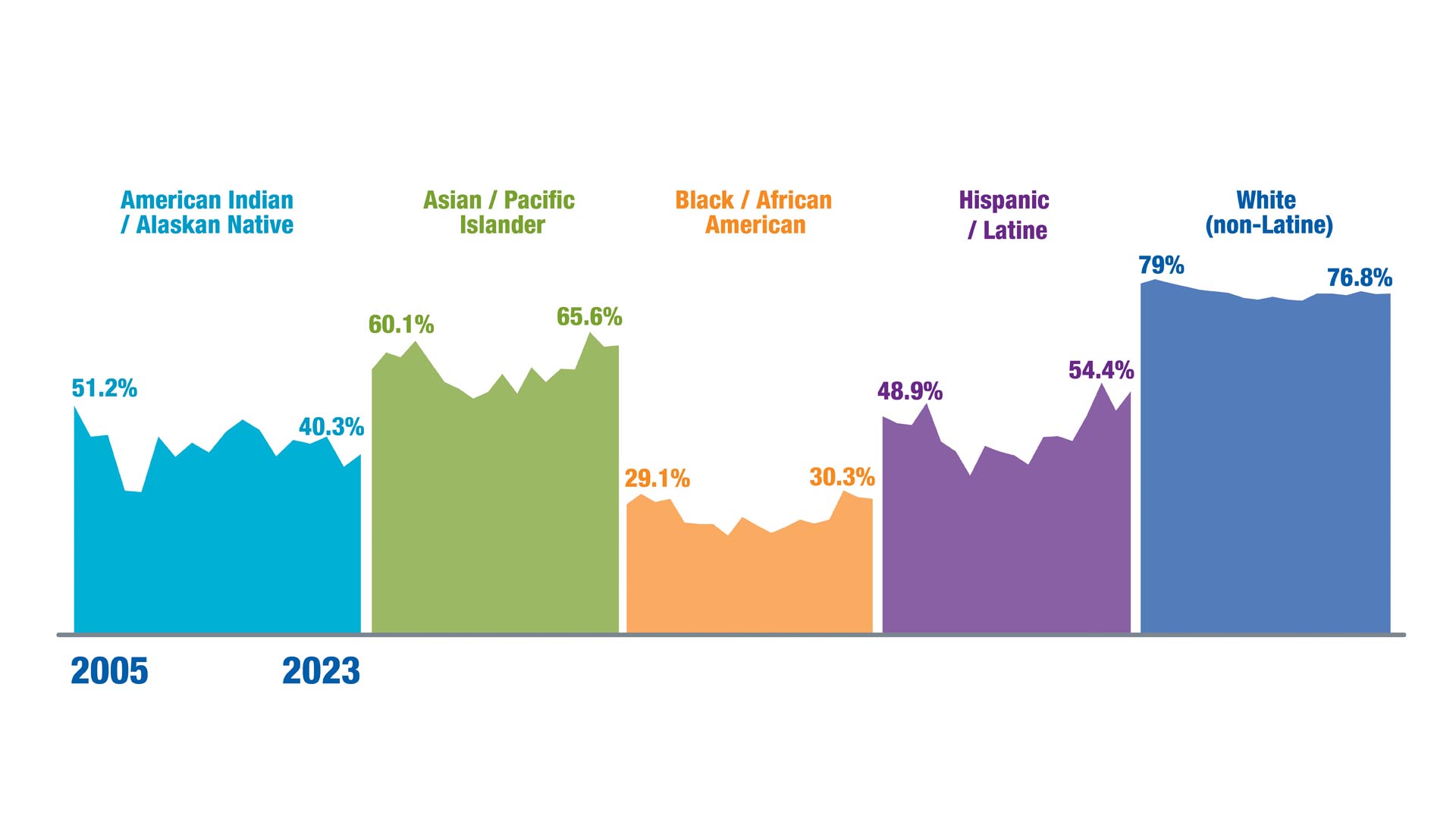

Homeownership rates are much higher and less volatile for white households

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, One-Year Estimates (Summary Files), 2005-2023. Data summarize tenure of occupied housing units in the 15-county MSA Householders who identified as Hispanic or Latine are not included in other race groups. This is the most disaggregation possible of race and ethnicity from this data source for this data point.

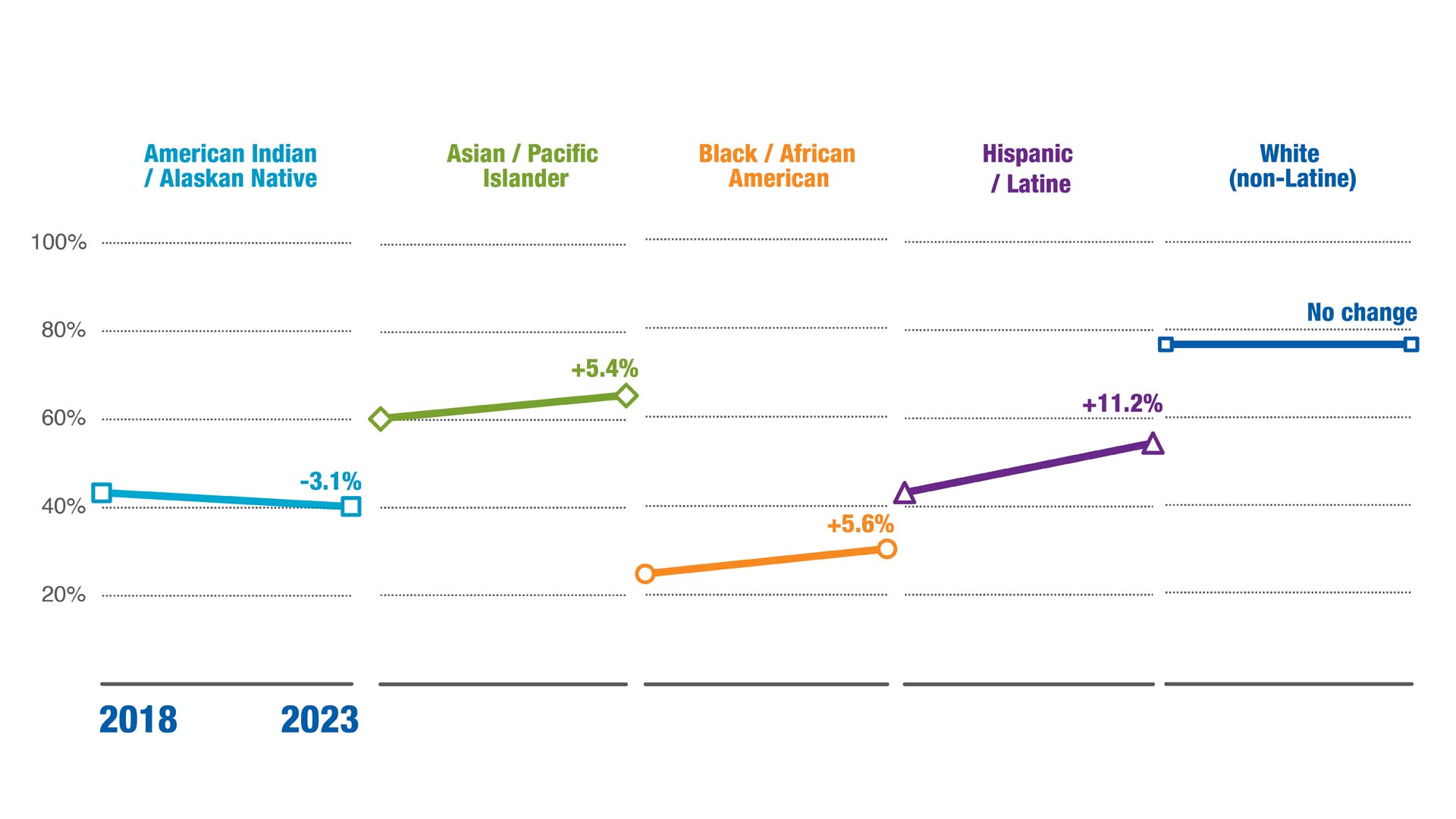

Homeownership is one of the primary modes of wealth building in the United States. Due to past and current public and private policies, racial disparities in housing equity account for a substantial share of the wealth divide. Currently, white households are 2.5 times more likely to own a home than Black households and 1.9 times more likely to own a home than American Indian households.21 Despite growth in homeownership rates for Black and Latine households in recent years, major disparities in access to homeownership persist.

Homeownership rates have increased for some race/ethnicity groups in recent years

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS), One-Year Estimates (Summary Files), 2018-2023. Data summarize tenure of occupied housing units in the 15-county MSA Householders who identified as Hispanic or Latine are not included in other race groups. This is the most disaggregation possible of race and ethnicity from this data source for this data point.

Even among households that own their homes, a substantial racial wealth gap exists, with households of color accumulating a lower return on investment. In 2021, the median net worth including home equity was $146,000 for white households, compared to only $16,200 for Black households.22

Racial inequities and discrimination in past policies have also played a role in the current racial gaps in homeownership and opportunities for generational wealth. For example, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, also known as the GI Bill, was intended to offer benefits to veterans after WWII. These benefits included low-interest mortgages, education benefits, unemployment benefits, and medical services. Despite this huge opportunity for homeownership support for veterans, Black individuals and their families faced discrimination when many banks refused to lend to these households and were often prohibited from moving into homes in the suburbs if they could get a loan. As a result, Black veterans did not have the same opportunity to build generational wealth through this policy that allowed many white veterans and their families new homeownership opportunities in the suburbs.23

Racial and ethnic disparities in intergenerational wealth transfers are also a component of the racial wealth gap. In 2022, white families were almost five times more likely than Hispanic or Latine households and almost four times more likely than Black households to receive an inheritance, and these racial and ethnic disparities have existed for decades.24 Home buyers who are beneficiaries of generational wealth are more likely to receive financial assistance from family members who have previously owned a home. As a result, they are more likely to make a down payment earlier in their lives as well as make more sizable down payments, which leads to lower interest rates and lending costs overall. This means households who have access to generational wealth, such as many white households in the region, accrue equity in their homes at an increased rate compared to households who do not have access to these benefits.

This divide in homeownership is not a natural occurrence or preference, nor is it due to the individual failings of people of color. This disparate access to ownership of homes is due to racist policies and practices with deep roots in discrimination and segregation that have continuing impacts.25 While it is easy to look back and point to racist policies in the past, the impacts of past and current policies and practices, and other racial inequities in access to homeownership, still exist today.

Black and Latine households are more likely to have their mortgage application denied relative to white applicants, even when accounting for other factors and characteristics of the borrower.26 Cultural differences in lending as well as immigration status can create barriers in accessing a traditional mortgage. If borrowers do obtain nontraditional mortgages, they may still face discrimination from sellers who choose to accept only traditional mortgages or cash offers. Despite fair housing laws prohibiting discrimination, evidence shows that discriminatory practices remain, including real estate agents steering Black households to or from certain neighborhoods.27

Housing discrimination impacts the quality of neighborhoods recommended to minority households, and constrained neighborhood choices lead these households to neighborhoods with lower quality schools, higher rates of assault, and higher rates of pollution exposure.28 Homeowners of color tend to own homes in historically underinvested communities, and homes in neighborhoods of mainly Black households are valued less than neighborhoods with mainly white households.29 These issues across our systems continue to create challenges in dismantling inequities in housing and wealth building for residents.

Homeownership is not the only path to wealth generation: fair wages, economic opportunity, and social support systems are also needed to narrow the wealth gap. However, with homeownership as the primary driver of wealth generation, there is a substantial need to target ownership opportunities for households facing the biggest barriers to wealth accumulation. Unfortunately, there is a shortage of affordable ownership opportunities in the region and fewer households can afford the increasing average sales price of a home in the region, which was $451,148 in 2024.30 This means there is demand in the region for more affordable homeownership opportunities, including ownership options such as manufactured homes, cooperative housing, and shared ownership. There is also demand for programs that remove barriers to homeownership for low-income residents.

17U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). Twin Cities Region (7-county). (2022). One-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS).

18U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). 15-County MSA. 2018 (adjusted to inflation) and 2023, 5-Year Estimates.

19U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. 15-County MSA. 2018 and 2022. 5-Year Estimates.

20U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Survey Year 2021, Public Use Data.

21U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). 15-County MSA. 2005-2023. 1-Year Estimates. Data summarize tenure of occupied housing units.

22.U.S. Census Bureau. (2021) Survey of income and program participation, survey year 2021, public use data. Data summarizes homeowners.

23.Tatjana Meschede, Maya Eden, Sakshi Jain, Eunjung Jee, Branden Miles, Mariela Martinez, Sylvia Stewart, Jon Jacob, and Maria Madison. (March 2022). IERE research brief: Preliminary results from our GI bill study. Brandeis University. Available at https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/gi-bill-final-report.pdf

24.Federal Reserve Board. (2022). Survey of consumer finances. Share that received an inheritance includes families who indicated having ever received an inheritance or having been given substantial assets in a trust or some other form. “Other” includes non-Hispanic residents who did not identify as white or Black. Summarized at the national level. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm

25.For more information, please refer to the Regional Goal Section: “Our region is equitable and inclusive” of the Imagine 2050 regional development guide.

26.Ky, Kim-Eng, and Katherine Lim. (May 1, 2022). The role of race in mortgage application denials. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. the-role-of-race-in-mortgage-application-denials.pdf

27.Hall, M., Timberlake, J. M., and Johns-Wolfe, E. (2023). Racial steering in U.S. housing markets: When, where, and to whom does it occur? Socius, 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231231197024

28.Christensen, Peter, and Christopher Timmins. Revised June 2021. Sorting or steering: The effects of housing discrimination on neighborhood choice. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24826/w24826.pdf

29.Rashawn, R., Perry, A., Harshbarger, D., Elizondo, S., and Alexander Gibbons. (2021 September). Homeownership, racial segregation, and policy solutions to racial wealth equity. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/homeownership-racial-segregation-and-policies-for-racial-wealth-equity/

30.Minneapolis Area Realtors Local Market Update. (November 2024). 13-County region, Rolling 12-month average: 13-County Twin Cities Region. https://maar.stats.10kresearch.com/docs/lmu/x/13-CountyTwinCitiesRegion?src=page

An official website of the

An official website of the