Housing stability as a foundation

As existing and new challenges around access to safe, affordable, and dignified housing in the region are approached and addressed, it is important to acknowledge the ways that stable housing supports resident health and well-being. The built and natural environments where people live, work, and play impact the health of the region’s residents. Housing is an important component to residents’ neighborhoods and living environments and is considered a social determinant of health, a nonmedical factor influencing physical and mental health.60 There are multiple connections between housing and health including the impacts of housing affordability, housing stability, physical housing conditions, and the surrounding neighborhood environment.61 The connections between housing stability and health show that stable housing is a foundation for improving household health outcomes, reducing homelessness, and providing a platform to build stability in other areas of residents’ lives.

Although housing instability and homelessness may look different in different areas, these issues exist in all areas of the seven-county region. Experiencing homelessness can mean a resident is living in shelters, sleeping on someone else’s couch, doubling up, in transitional housing, living in a hotel or motel, or sleeping outside. Despite a 7.5% decrease from 2018 in the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in the seven-county region, in 2023, there were 6,254 individuals counted experiencing homelessness (in shelter, outside, on transit, or temporarily doubled up) on a single night in the seven-county region.62

In our region, 72% of adults experiencing homelessness reported having a chronic physical health condition in the last 12 months, significant mental illness in the last two years, or substance use disorder in the past two years.63 In general, individuals experiencing homelessness have higher rates of disease such as depression, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or Hepatitis C. They may face a combination of multiple health issues or disabling conditions, as well as having increased exposure to communicable diseases, violence, and malnutrition.64 Additionally, when residents do not have stable housing, it can be harder to manage existing health conditions or recover from an illness. Those experiencing homelessness also have increased mortality rates. The rate of death is three times higher for all people experiencing homelessness in Minnesota and five times higher for American Indian people experiencing homelessness as compared to the general Minnesota population.65

Although anyone can be at risk of housing instability, low-income households and households of color face more challenges to maintain housing stability. Black, African American, African and American Indian individuals make up a larger portion of the population experiencing homelessness in the region compared to their overall population size within the region.66 The challenges of housing stability also disproportionately affect youth in the region. People age 24 and younger make up over 40% of the population experiencing homelessness in the seven-county region.67

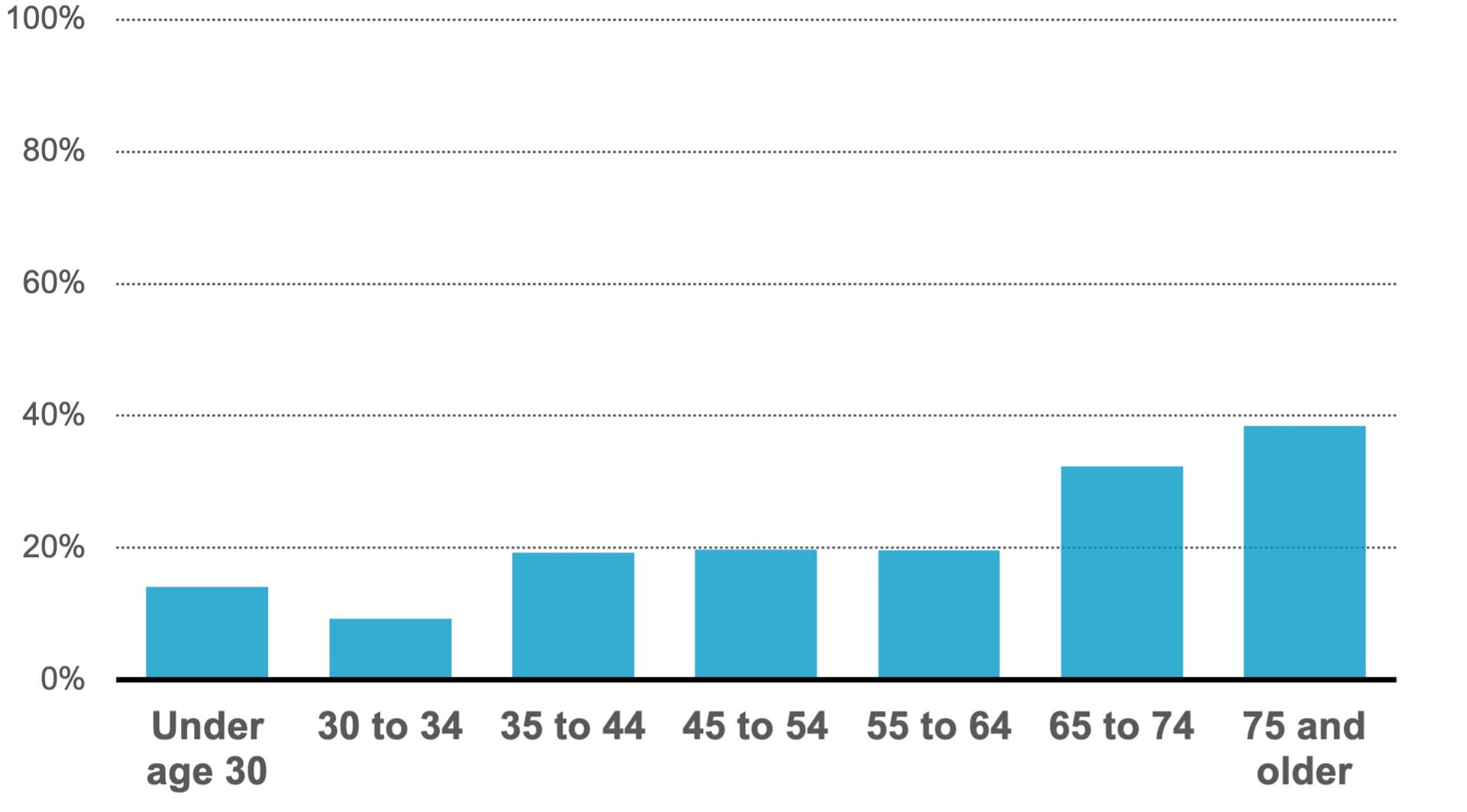

Young people are overrepresented in the population of people experiencing homelessness

Source: Wilder Research, 2023 Minnesota Homeless Study. Note: 78 people counted experiencing homelessness are categorized as "age unknown” because demographic data were not reported or were unknown.

Proportionally, older adults (aged 55 and over) currently experience homelessness at much lower rates than younger people (aged 24 and less) in the seven-county region. However, forecasts show significant growth for the older adult population (aged 65 and over) in the next decade. This is expected to lead to significant increases in the cost of shelter, health care, and other long-term care needs for this population.68 Similar to local, regional, and national efforts to address homelessness today, how we plan for the future needs of the older adult population will have lasting impacts on the well-being of residents. These impacts may include the rates of avoidable disease, premature disability, and mortality.

Of all residents experiencing homelessness in the seven-county region, almost 18% are not in a formal shelter.69 Although emergency shelter plays an important role in our housing system, it can be inaccessible, may not be culturally responsive, is not present in all areas of the region, and may not be safe for all residents. Due to these limitations and other challenges faced by those experiencing homelessness, informal settlements have been used as shelter across the seven-county region. A harm reduction approach is needed in government and community responses to informal settlements and the challenges faced by those living in informal settlements.

Housing instability can look different for different households, can be impacted by different factors, and can last for different durations of time. Housing instability can include shorter-term instability such as moving frequently, formal and informal evictions, falling behind on rent, or doubling up. These situations can affect household well-being by increasing stress, anxiety, and depression. These challenges can lead to disruptions in employment, education, medical care, and access to other social services.

There are many reasons residents may move more frequently. However, lower-income households are more likely to move frequently and may be forced to rent substandard housing. Very low-income individuals are the residents most at risk of housing instability, and they rely heavily on informal housing arrangements, which can mean being subject to moves that were not planned. In 2022, 87% of households in the region were living in the same housing unit as the previous year, but only 78% of very low-income households were living in the same unit as the previous year.70

In 2022, following the end of the Minnesota eviction moratorium that had been in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of evictions for the year in the region were the highest they had been since 2013, and eviction rates continued to rise, surpassing the 2013 rate in 2023.71 Because the most common reason for eviction filing in the state post-pandemic was nonpayment of rent, these rates rising above pre-pandemic levels suggest that residents are facing more financial challenges than they did in the years leading up to the pandemic.72 Beyond the immediate instability caused by an eviction action, evictions can be a significant barrier to accessing housing again in the future. Even if a resident was not evicted, the eviction action can stay on a resident’s record, visible to property owners on a tenant screening assessment when applying for future housing opportunities.

Despite evidence-based housing models and interventions to reduce homelessness, increase housing stability, and reduce hospitalization – such as permanent supportive housing and, more specifically, the Housing First approach – more resources are needed.73 Programs and supportive services have not been funded at the scale required to address current needs.

Supportive housing – affordable housing paired with home and community-based services for those who have chronic mental or physical health conditions – can include access to health care, mental health supports, substance use supports, or other services that help people get into and stay in their housing.74 Supportive housing is an important intervention and is a housing sector that faces challenges that could worsen the landscape of homelessness if not addressed.

These challenges include:

- Increased cost of services

- Increased insurance costs

- Increased complexity or severity of health conditions requiring specialized services

- System challenges with the referral process for units

- Lack of affordable units

- Cost of repairing aging infrastructure

- Lack of funding for operations and property management

- Displacement from current supportive housing

Those not able to access supportive housing risk facing homelessness and relying on systems and institutions not equipped to address their needs.

Estimates are that there is a shortage of 15,375 supportive housing units in the state of Minnesota, and the subpopulation with the largest need for supportive housing is the aging population (3,982 units), followed by those in mental health institutional settings (1,788), and those experiencing chronic homelessness (1,300).75 Without providing adequate integrated housing and health support through these units, residents are faced with cycling through alternative institutions and systems that can diminish the health, stability, and well-being of residents while putting a significant financial strain on public resources.

Having a stable place to live is an important component of an interconnected system with other supports necessary for people to thrive in their communities. Important interventions to reduce housing instability and prevent displacement include low-barrier direct assistance for housing (emergency assistance and long-term subsidies), eviction prevention programs, foreclosure assistance, partnerships that allow for low-barrier access to support services, increased tenant protections, rent stabilization policies, supports for those with disabilities, supports for residents facing domestic violence, youth- and family-focused supports, programs that ensure safe living environments like rental licensing programs and code enforcement, climate disaster relief, and emergency shelter options. Despite the increased cross-sector collaboration and community-wide investment needed to address housing instability, more interventions and investment are needed to allow all residents in the region opportunities for stability and the improved health benefits that come from safe and stable housing.

60. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) Healthy people 2030 – Social determinants of health: Housing instability. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/housing-instability

61. Health Affairs. (June 2018). Housing and health: An overview of the literature. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/housing-and-health-overview-literature

62. Wilder Research. (March 2024). 2023 Minnesota homeless study counts data tables. https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/minnesota-homeless-study/2023/counts/Metro-2023-Homeless-Counts_3-24.pdf?v=2

63. Wilder Research. (June 2024). Homelessness in the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota. https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/2023Homeless_TwinCities-GreaterMN_Brief1_6-24.pdf

64. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (February 2019). Homelessness and health: What’s the connection? Fact sheet. February 2019. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf; and National Alliance to End Homelessness. (December 2023). What is homelessness in America? https://endhomelessness.org/overview/

65. Minnesota Department of Health. (November 2023). Minnesota homeless mortality report, 2017-2021. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/homeless/coe/coephhmr.pdf

66. Wilder Research. (March 2024). Single night count of people experiencing homelessness: 2023 Minnesota homeless study counts data tables. https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/minnesota-homeless-study/2023/counts/Metro-2023-Homeless-Counts_3-24.pdf?v=2

67. Ibid

68. Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy – University of Pennsylvania. (2019). The emerging crisis of aged homelessness. https://aisp.upenn.edu/aginghomelessness/

69. Wilder Research. (March 2024). Single night count of people experiencing homelessness: 2023 Minnesota homeless study counts data tables. https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/minnesota-homeless-study/2023/counts/Metro-2023-Homeless-Counts_3-24.pdf?v=2

70. U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). 5-Year Estimates. 2022. 7-County region.

71. Hennepin County. Evictions in Hennepin County - Dashboard. https://app.powerbigov.us/view?r=eyJrIjoiYzQ1NDQyY

zUtZDY2Zi00OTIxLThiZDgtZGQ3MWYwZjM5NmQ0IiwidCI6IjhhZWZkZjlmLTg3ODAtNDZiZi04ZmI3LTRjOTI0NjUzYThiZSJ9

72. HOMELine. (July 12, 2022). Eviction filing rates a year after the eviction moratorium. https://homelinemn.org/9410/eviction-filing-rates-a-year-after-the-eviction-moratorium/

73. Minnesota Management and Budget. Minnesota inventory. https://mn.gov/mmb/results-first/inventory/

74. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (May 2016). Supportive housing helps vulnerable people live and thrive in the community. https://www.cbpp.org/research/supportive-housing-helps-vulnerable-people-live-and-thrive-in-the-community

75. Corporation for Supportive Housing. (2024). Supportive housing need in the United States. https://www.csh.org/

An official website of the

An official website of the