The State of the Regional Parks and Trails System

Demographic and economic trends, social issues, relationships, investments, and infrastructure shape the Regional Parks and Trails System today, as well as its future. To prepare for 2050, the policy plan identifies these existing conditions as a foundation for future priorities and direction.

Through research, agency collaboration, stakeholder engagement, and observation of large-scale trends, Imagine 2050 identifies four key existing conditions in addition to the broader landscape of the region, with specifics detailed in other policy chapters of Imagine 2050 and provided under Section One of the Regional Parks and Trails Planning Handbook. Understanding these conditions informed the System vision, mission, values, objectives, policies, and actions.

Vital to people and communities

Regional parks and trails are important to people for multiple reasons including public health, social connections, and recreation opportunities. With changing demographics, the Regional Parks and Trails System will need to assess ways to continue being a relevant service for current and future visitors.

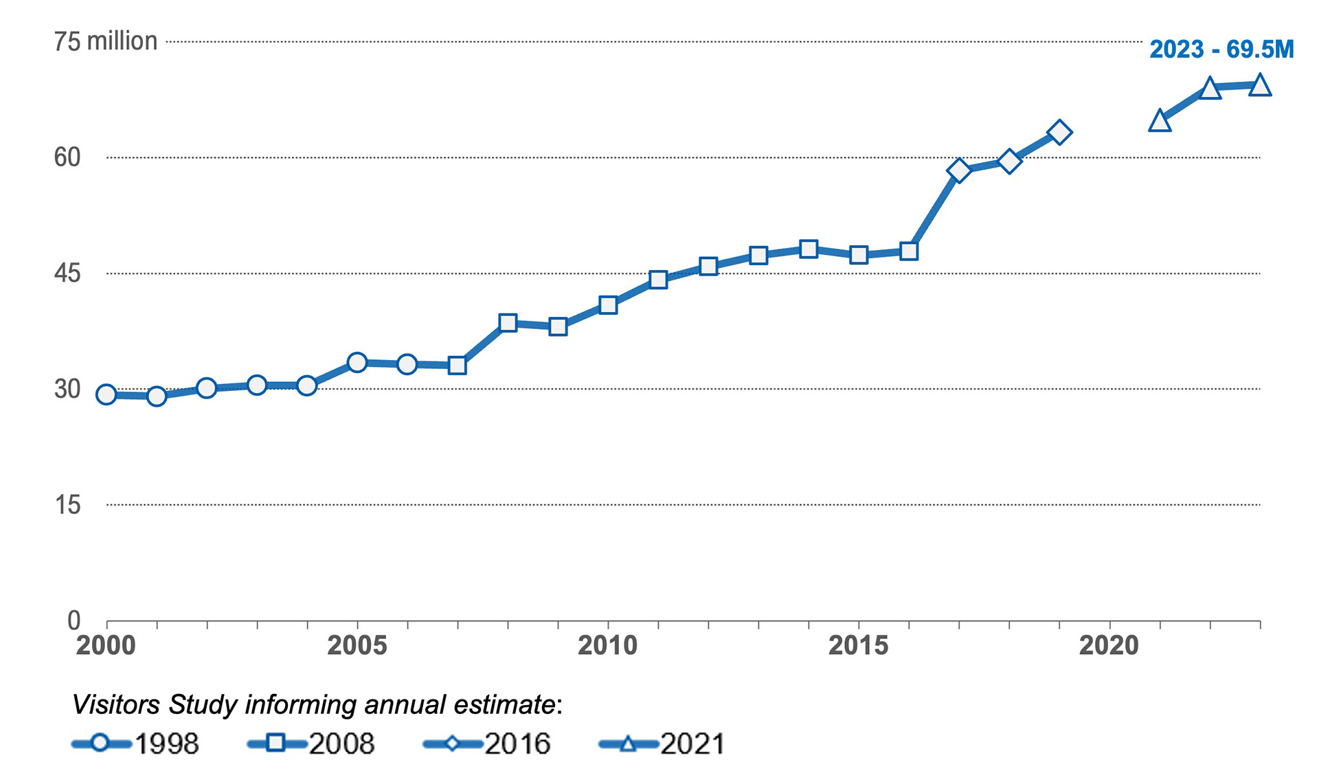

The Regional Parks and Trails System is a highly valued amenity to the Twin Cities metro area with over 69 million visitors in 20234 (see Figure 1.6, below). Park and trail users generally have a positive experience, with 88% of visitors in 2021 ranking the facilities as “Excellent” or “Very Good.”5 The system provides many benefits to its visitors, ranging from simple time in nature to recreational opportunities to increased happiness to social connectivity.

Figure 1.6: Visits to the Regional Parks and Trails System have more than doubled since 2000

Source: Metropolitan Council’s annual population estimates and annual parks and trails use estimates (July 2024). Park use estimates are calculated using a multiplier factor that is collected during the Metropolitan Council’s Visitors Study (typically completed once every five years). We recommend caution comparing use estimates informed by different visitors studies.

Access to parks and trails reduces medical costs, increases community trust, and provides mental health benefits. It increases positive emotions like calmness, joy, and creativity. Connection to nature is a low-cost public health measure compared to conventional medical interventions.6 Thousands of articles and four decades of peer-reviewed research publications lead to one general conclusion: Time outdoors will improve anyone’s physical and mental health. When people get outdoors - into the parks and on the trails - health care is moved “upstream,” from curing sickness in the medical system to preventing it.

"Community gatherings are in parks, and this is a way to get to know neighbors. ...People meet friends in Parks"

Youth leader, Roseville

As the system continues to grow and change, regional parks and trails must continually adapt to new challenges. For example, parks may be a potential solution to public health emergencies. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, people gathered in parks as a form of recreation and sanctuary when many other options were unavailable. In a 2023 post-pandemic survey from the National Recreation and Parks Association, 80% of park and recreation professionals across the country reported that current visitation levels were higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The system can also help address loneliness and social isolation. Social isolation and loneliness affect millions of Americans and come with harmful health impacts. In a recent U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory, loneliness and social isolation can increase the risk of premature death by 26% and 29% respectively. Regional parks and trails can help reverse this trend by providing social spaces for the region and building greater social connections.

While regional parks and trails are a highly valued amenity for our region, they are out of reach for some communities for a variety of reasons. In the 2021 Parks and Trails Visitor Study, Black people, Indigenous people, people of color, and young people were underrepresented as a proportion of visitors to the system (see Figure 1.7). Among communities of color, the most common barriers to access are lack of awareness, time constraints, safety concerns, and transportation barriers. In the 2021 Youth and Parks report, the top barriers identified for young people were safety concerns, a lack of opportunity to learn necessary skills, and racism and exclusion.

Figure 1.7: People of color, youth, and low- and very high-income residents are underrepresented in Regional Park and Trail System visits Comparing the share of visitors by demographic topic (in color) with regional demographics (in grey)

Source: Metropolitan Council’s 2021 Regional Parks and Trails Visitor Study; U.S. Census Bureau, decennial census, 2020 (race and ethnicity, age); U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey one-year estimates, 2021 (household income, disability). Disparities between visitors and the region’s population greater than 2% are highlighted in yellow.

It is crucial that the Regional Parks and Trails System works to identify, address, and reduce these barriers to these underserved communities, especially because the region will only become more diverse in the future. It is expected that in 2050, 45% of the region will be Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color, and 22% of the population will be 65 years or older. With a significant change in population, regional parks and trails must continually change and improve to best meet the needs of the Twin Cities region.

History of inequitable development

Through partnership and coordination, the Regional Parks and Trails System developed into the expansive system we recognize today. However, systemic racism has played a role in shaping the use and development of these recreational spaces.

The land that the Regional Parks and Trails System sits on is the ancestral land of the Dakota and the Ojibwe, which was stolen from them through a series of ill-intentioned treaties that were often enacted under pressure from the U.S. government. With continued growth of the Twin Cities and harsh punishments resulting from the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, the Dakota were ultimately pushed out of their homelands and forced to reside on small reservations throughout Minnesota and elsewhere.

The resulting displacement also separated the Dakota from the Bdote, the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. These places are sacred and provide deep connection to the Dakota people as the place of their origin stories. Nearby places hold significant cultural and spiritual meaning. The Owámniyomni Okhódayapi organization writes of efforts to reconnect American Indian communities to the Bdote and other cultural treasures: “Native communities are still fighting to resurrect and protect their culture, language and history. We can help restore this story disrupted.”7 With regional parks and trails sited on American Indian lands, the system must address a way forward to respect the land and the people who have deep ties to these spaces.

Regional parks and trails are also influenced by racist policies in housing development. Redlining and racial covenants created in the early 20th century restricted neighborhoods to only certain white communities. Combined with housing developers’ efforts to ensure parks were built near their investments, these Progressive Era policies had the impact of racially segregating those who visited lakeside parks in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. Today, there is strong evidence of a connection between these earlier redlining practices and areas with increased temperature, decreased tree canopy, and more impervious surfaces.8

Today, the legacy of inequity continues to persist in overburdened communities as seen with the large gaps in visitation demographics, especially among Black residents. White residents comprise 68% of the region’s population but account for 84% of regional park visits. Meanwhile, Black residents comprise 10% of the region’s population, but account for only 4% of regional park visits.9 Some common barriers to access include a lack of awareness, time constraints, and safety concerns. The creation of the Regional Parks and Trails System started with a desire to collaborate and protect the natural beauty of the Twin Cities, but it also comes from a government that was associated with systemic racism. To move forward by 2050, it will be critical to address the legacy of racial inequity and work toward creating a more desirable future.

The climate is changing

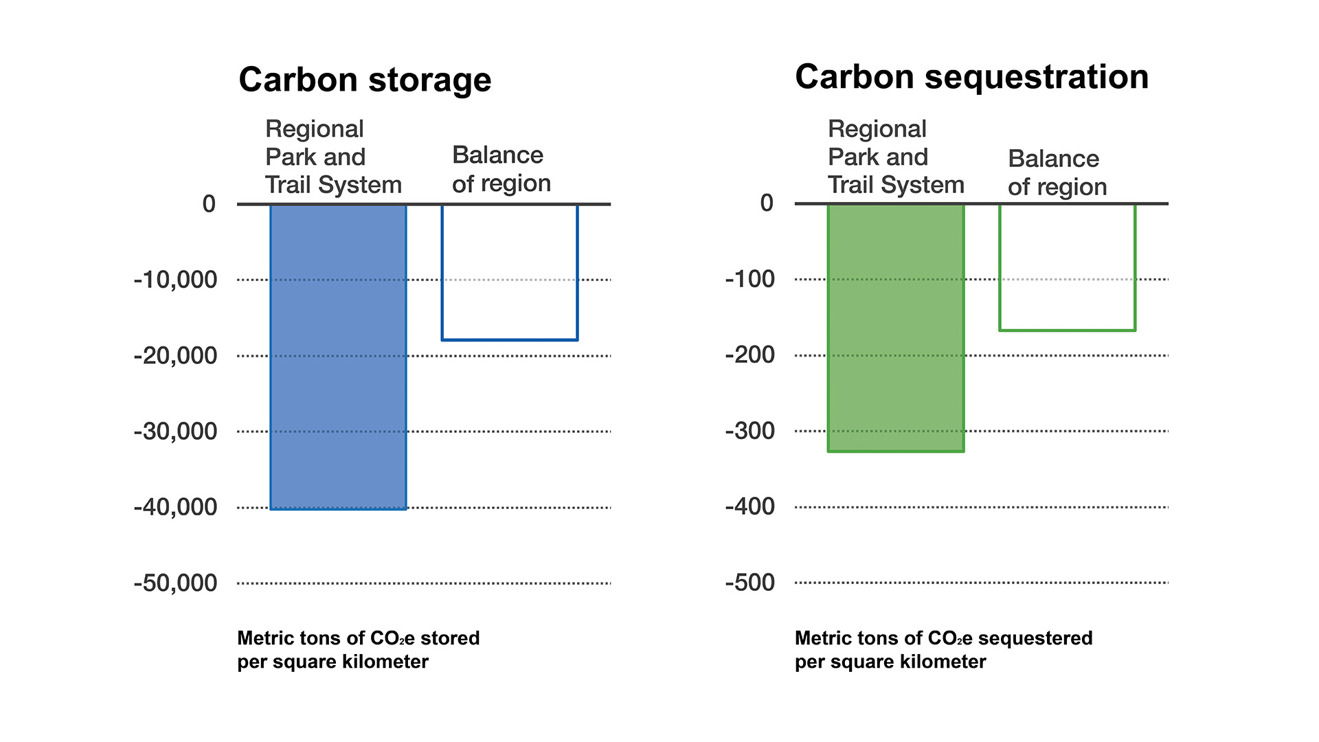

Climate change has already begun to impact life in the Twin Cities region with intensifying weather events, warming winters, and hotter summers. The Regional Parks and Trails System is a key tool for applying mitigation and adaptation strategies (Figure 1.8).

To adequately prepare for 2050, the Regional Parks and Trails System plans to mitigate climate change while adapting to the on-the-ground impacts to the region. With average annual temperatures in the Twin Cities region warming by nearly three degrees Fahrenheit since 1895,10 the impacts of climate change to recreation and natural systems are already being felt. Regional parks and trails are greatly impacted by these changes, resulting in new realities such as habitat loss for native species, shorter winters, earlier ice outs, and increased frequency of extreme heat and poor air quality.

It is also important to note that low-income and communities of color are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. For example, areas in Minneapolis that had racial covenants (properties that could only be sold to whites) have temperatures that are on average 3.71 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the rest of the city.11 Racial covenants were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and are no longer enforceable, but the effects of these covenants can still be seen and felt today.

Another aspect of climate change is the impact it has on water quality. Throughout the central and metropolitan areas of Minnesota, only 54% of lakes meet water quality standards for recreation.12 Due to algal blooms, littering, and pollution, the recreational opportunities for park visitors have diminished slightly.

While climate change is already being felt around the region, parks and trails can provide many environmental benefits as they break up and ameliorate the effects of urban heat islands, improve air quality, sequester carbon, and provide flood-storage benefits. Parks and trails also protect natural habitats, providing increased biodiversity while maintaining healthy ecosystems.

Figure 1.8: The Regional Parks and Trails System mitigates greenhouse gases by storing and sequestering carbon at rates twice that of other areas

Source: Metropolitan Council analysis of the USGS National Land Cover Database and primary literature sequestration rates within census municipality boundaries and regional park boundaries.

Throughout the Regional Parks and Trails System, work is underway to increase the environmental benefits that were previously mentioned. A 2021 work group made up of implementing agency and Met Council staff identified the following efforts:

- Restoring lands to native plant communities or species resilient to new climates

- Protecting large areas of land to provide habitat for native species like bison and the rusty patched bumblebee

- Adapting recreational opportunities like adjusting open hours to allow for more recreation in cooler evening hours

As implementing agencies continue efforts to build a more resilient future, it is important that the Met Council continues to support this work, while also striving to think of new ways to address these challenges.

Growing pains

The Regional Parks and Trails System has experienced rapid growth over the past few years, especially regional trails. This expansion must be balanced with the need to secure adequate funding for regular maintenance.

Since the creation of the Regional Parks and Trails System in 1974, the system has grown substantially, totaling more than 60,000 acres of park land protected and almost 490 miles of regional trails. This has been achieved due to the investment of over $1 billion in state and regional dollars and an additional $244 million of state funds for operations and maintenance funding (2024 figures) in addition to hundreds of millions of dollars invested in operations, programming, and capital improvements by the implementing agencies themselves.

The overall success of a large parks and trails system in the Twin Cities region has led to an expectation of high-quality amenities. In the 2021 Regional Parks Visitor Study, respondents were asked to suggest recommendations that would improve their experience visiting regional parks and trails. The most common recommendations for improvement were maintenance for regional parks (20%) and better surface conditions for regional trails (23%).

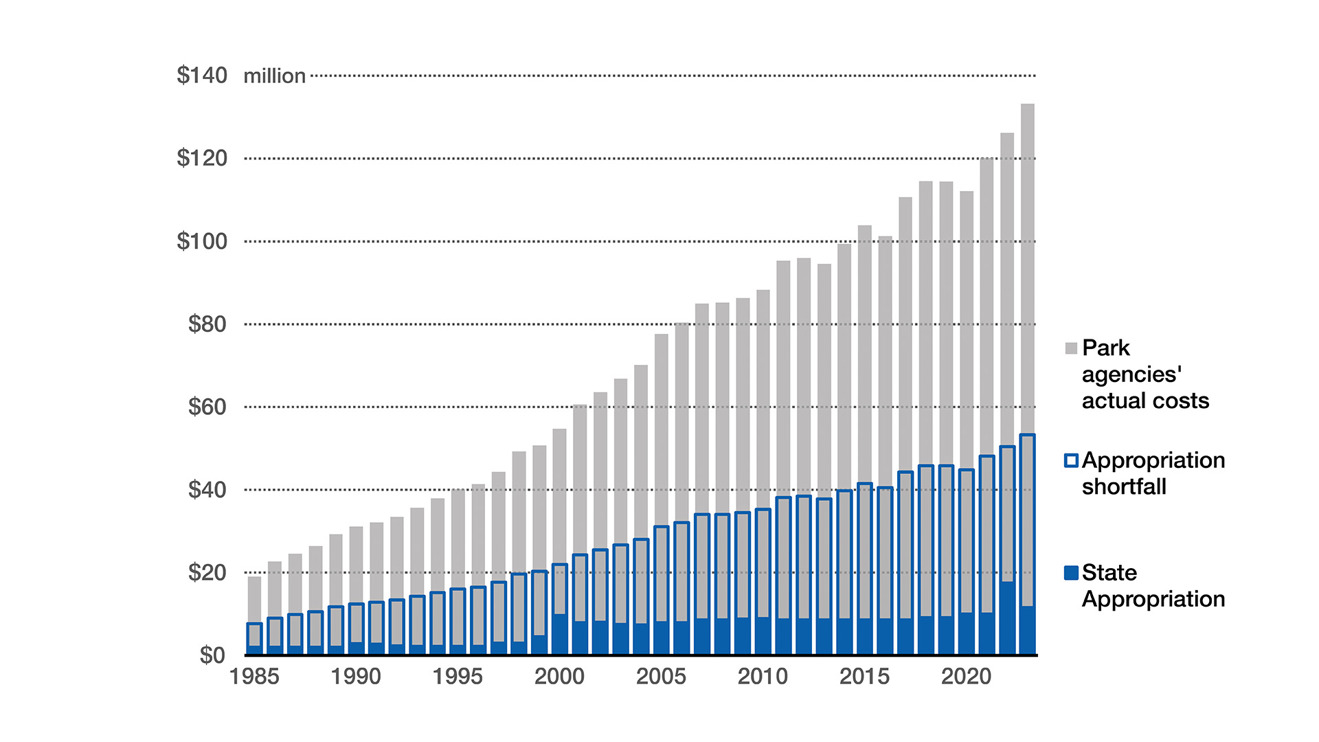

Despite the high demand for improved and well-maintained amenities, the regional park implementing agencies are facing a gap in funding for operations and maintenance. When it comes to financing the system’s operations and maintenance costs, the state has historically invested significantly less than its statutorily required 40% of total operational costs, instead appropriating, on average, 9% of these costs (see Figure 1.9).

In addition to the regular demands of maintaining and upgrading infrastructure, there is also a desire to continue expanding the system, to improve access to underserved communities, protect natural areas, and plan for developing areas and the growing population.

Figure 1.9: State funding falls short of appropriation commitment as costs increase for agencies

Appropriated funding from the State of Minnesota and operations and maintenance costs incurred by regional park implementing agencies

Source: Metropolitan Council analysis of Operations and Maintenance appropriations and park agency annual expenditures.

4 Metropolitan Council (2024) Visits to the regional park system in 2023, p.1. https://metrocouncil.org/Parks/Publications-And-Resources/PARK-USE-REPORTS/Annual-Use-Estimates/2023-Visits-to-the-Regional-Parks-and-Trails-Syste.aspx

5 Metropolitan Council (2021) 2021 Parks and trails visitor study, p. 3. https://metrocouncil.org/Parks/Research/Visitor-Study.aspx#Report

6 Metropolitan Council (2021) Adventure close to home: Connecting youth to the regional park system (1):3. https://metrocouncil.org/Parks/Research/Youth-Parks/Report.aspx

7 Owamniyomni Okhodayapi, www.owamniyomni.org, About section, 2024.

8 Hoffman JS, Shandas V, Pendleton N. (2020) The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: a study of 108 US urban areas. Climate 8(1):12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338556690_The_Effects_of_Historical_Housing_Policies_on_Resident_Exposure_to_Intra-Urban_Heat_A_Study_of_108_US_Urban_Areas

9 Metropolitan Council (2021) 2021 Parks and trails visitor study, pp.13-14. https://metrocouncil.org/Parks/Research/Visitor-Study.aspx

10 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Climate trends. Climate change and Minnesota. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/climate/climate_change_info/climate-trends.html

11 Walker, R.H., Keeler, B.L., Derickson, K.D. (2024) The impacts of racially discriminatory housing policies on the distribution of intra-urban heat and tree canopy: A comparison of racial covenants and redlining in Minneapolis, MN, Landscape and Urban Planning, 245. https://experts.umn.edu/en/publications/the-impacts-of-racially-discriminatory-housing-policies-on-the-di

12 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Lake water quality. Water quality. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/lake-water-quality

An official website of the

An official website of the