Regional Vision, Values, and Goals

Introduction to the regional development guide

Table of Contents

Imagining and Planning for an Equitable and Resilient Future

The role of regional planning

How Imagine 2050 is organized

How this plan works and relates to the other Met Council plans

Dakota Makoce k'a Mni Okiciyaka

One decade's two eras: How our region has changed since 2014

Socially and environmentally, our region is changing

The people of our region

Our region's economy

Regional Vision, Values, and Goals

Vision for Imagine 2050

Shared regional values

Regional goals

Our region is equitable and inclusive

Patterns of historical injustices

Equity framework

Environmental justice framework

Anti-displacement framework

Community-centered engagement

Land, water, and people acknowledgment and Met Council commitments to act

Our communities are healthy and safe

Health and safety begin in communities

Social connection combats the loneliness epidemic

A built environment where residents "feel seen" cultivates a sense of dignity

Rewarding lives are created in communities where residents feel safe and respected

Healthy and safe communities in Imagine 2050

Our region is dynamic and resilient

Our region's economic assets

What holds our economy back now and in the future

Opportunities for an economically resilient future

We lead on addressing climate change

Renewed commitment on climate

Climate connections to natural systems

Climate connections to environmental justice

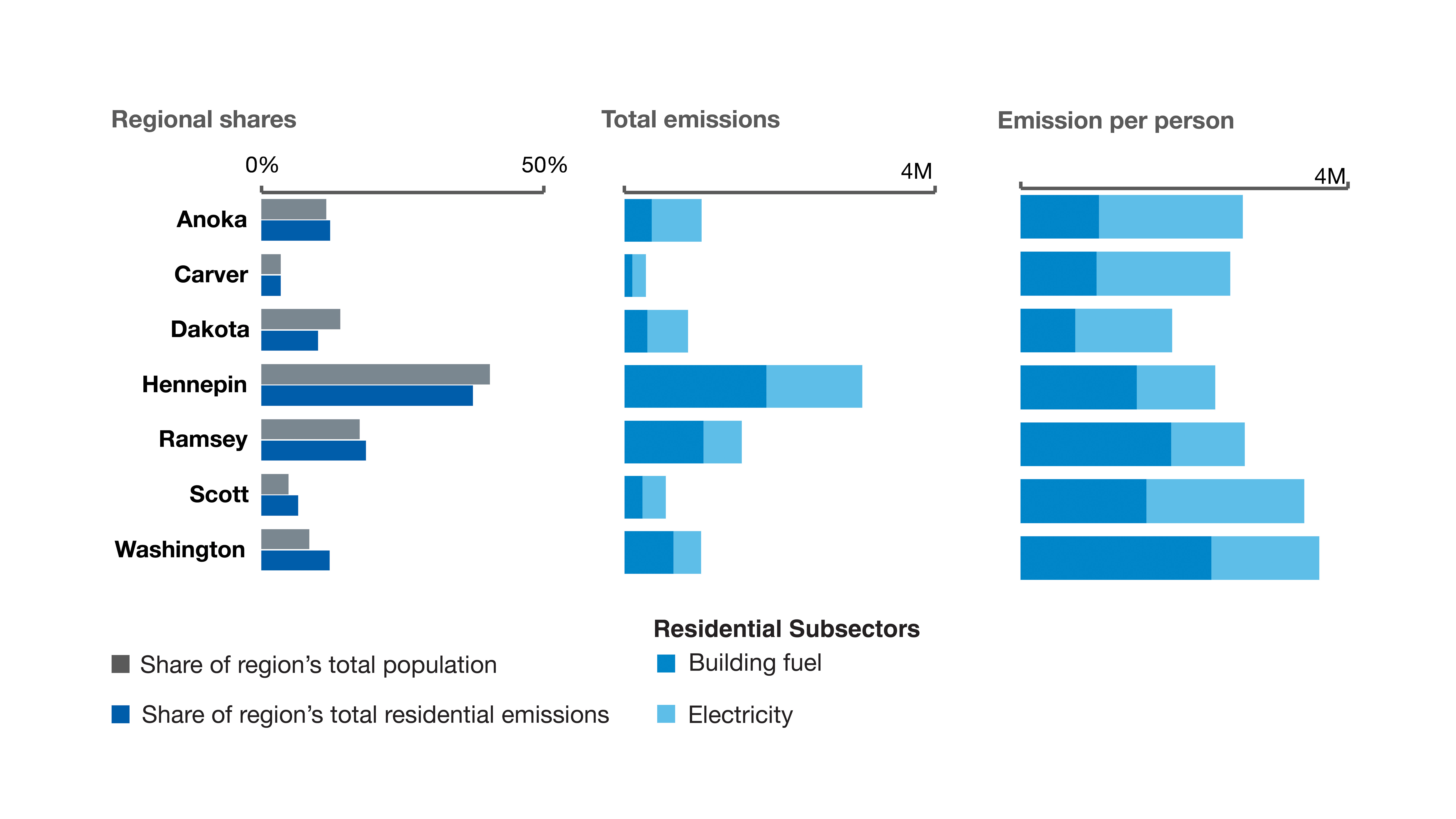

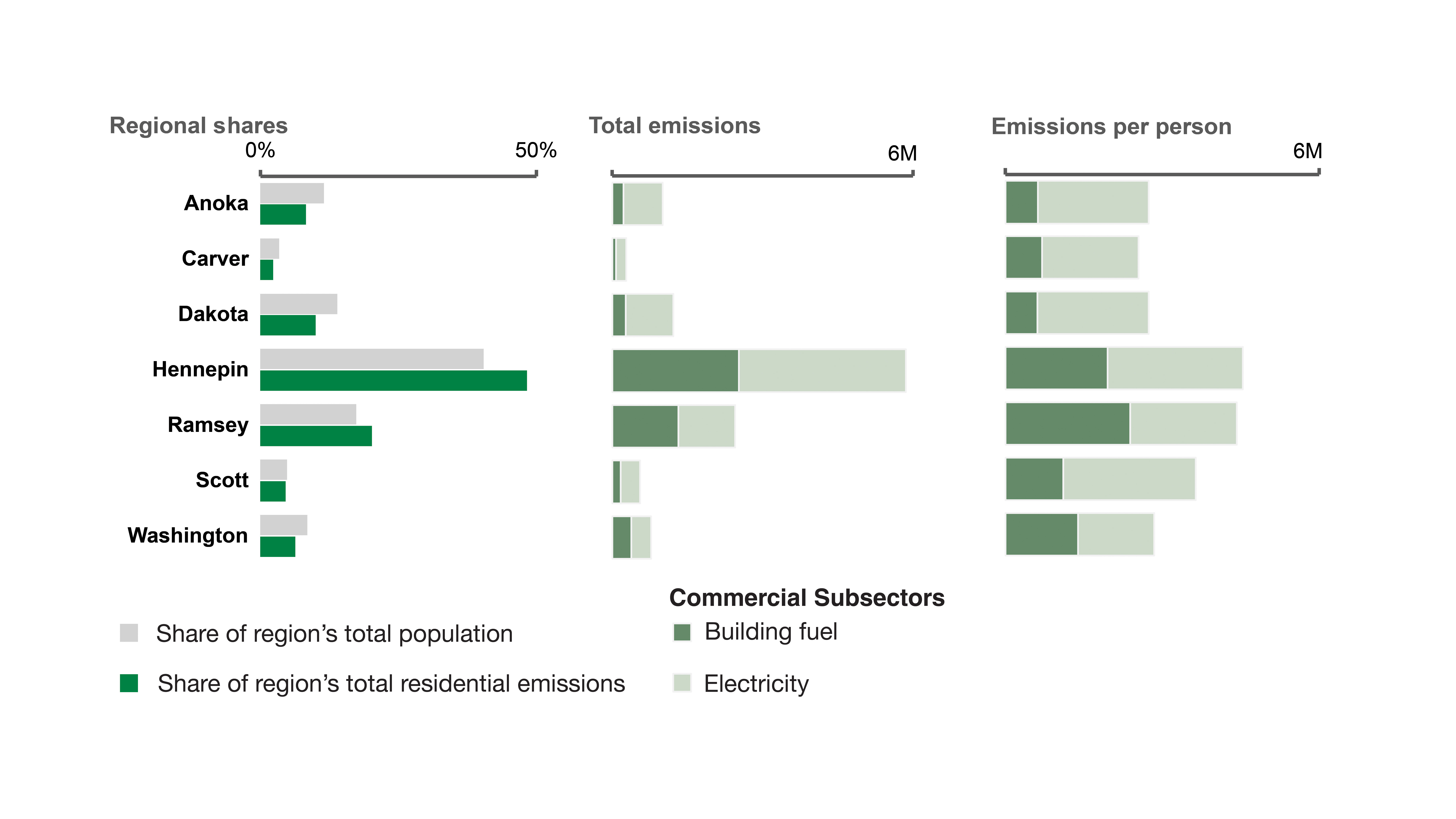

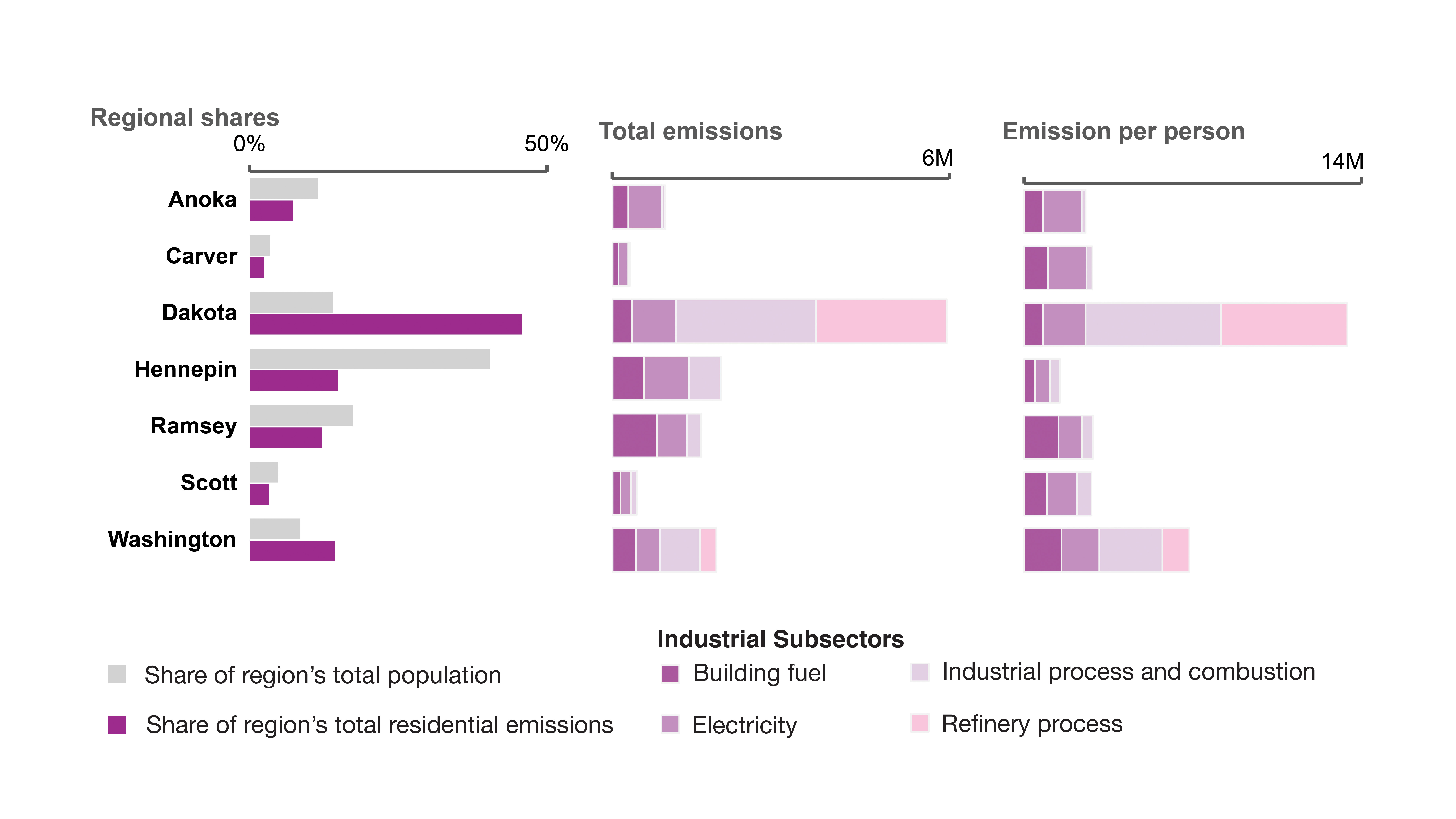

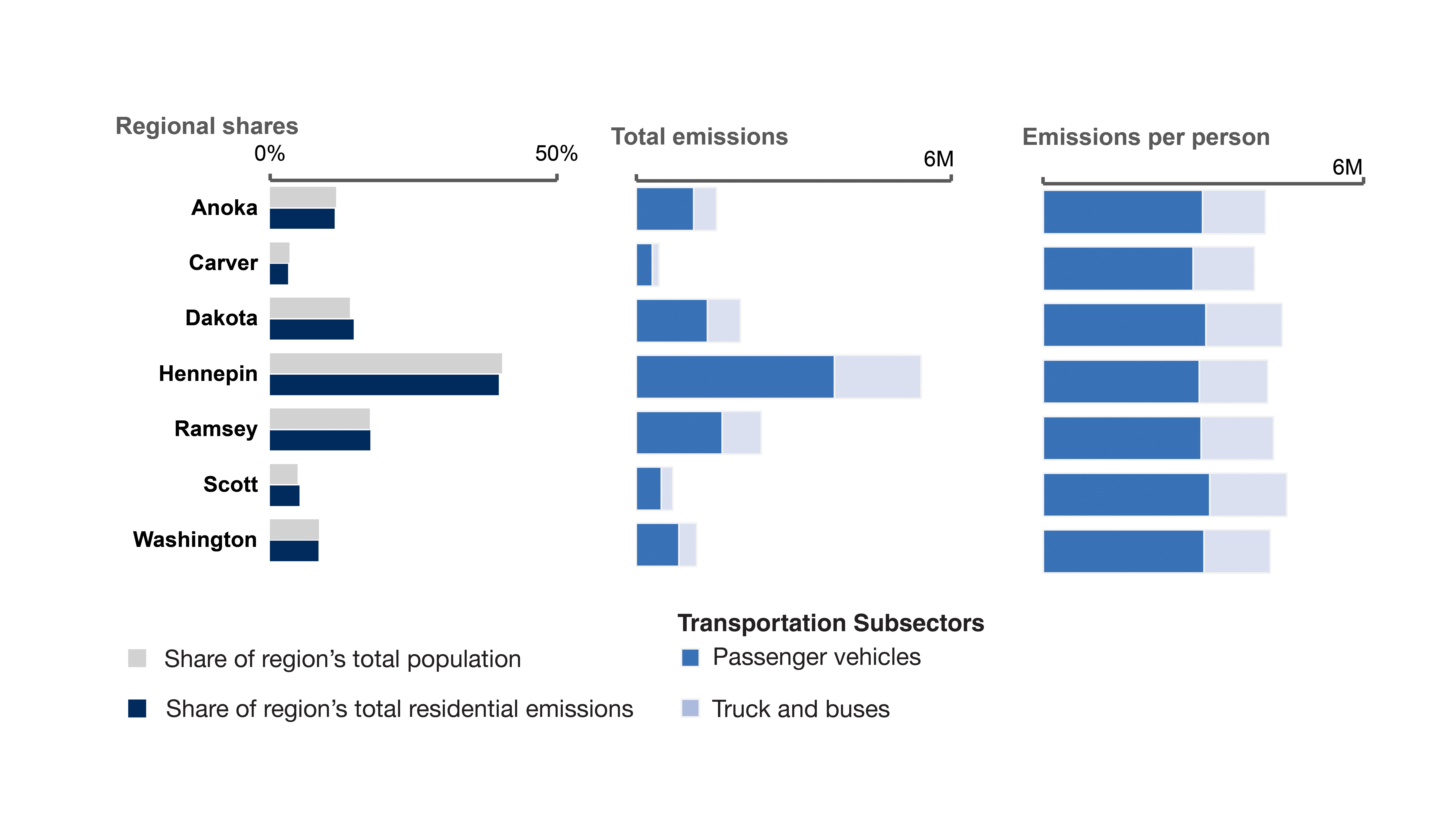

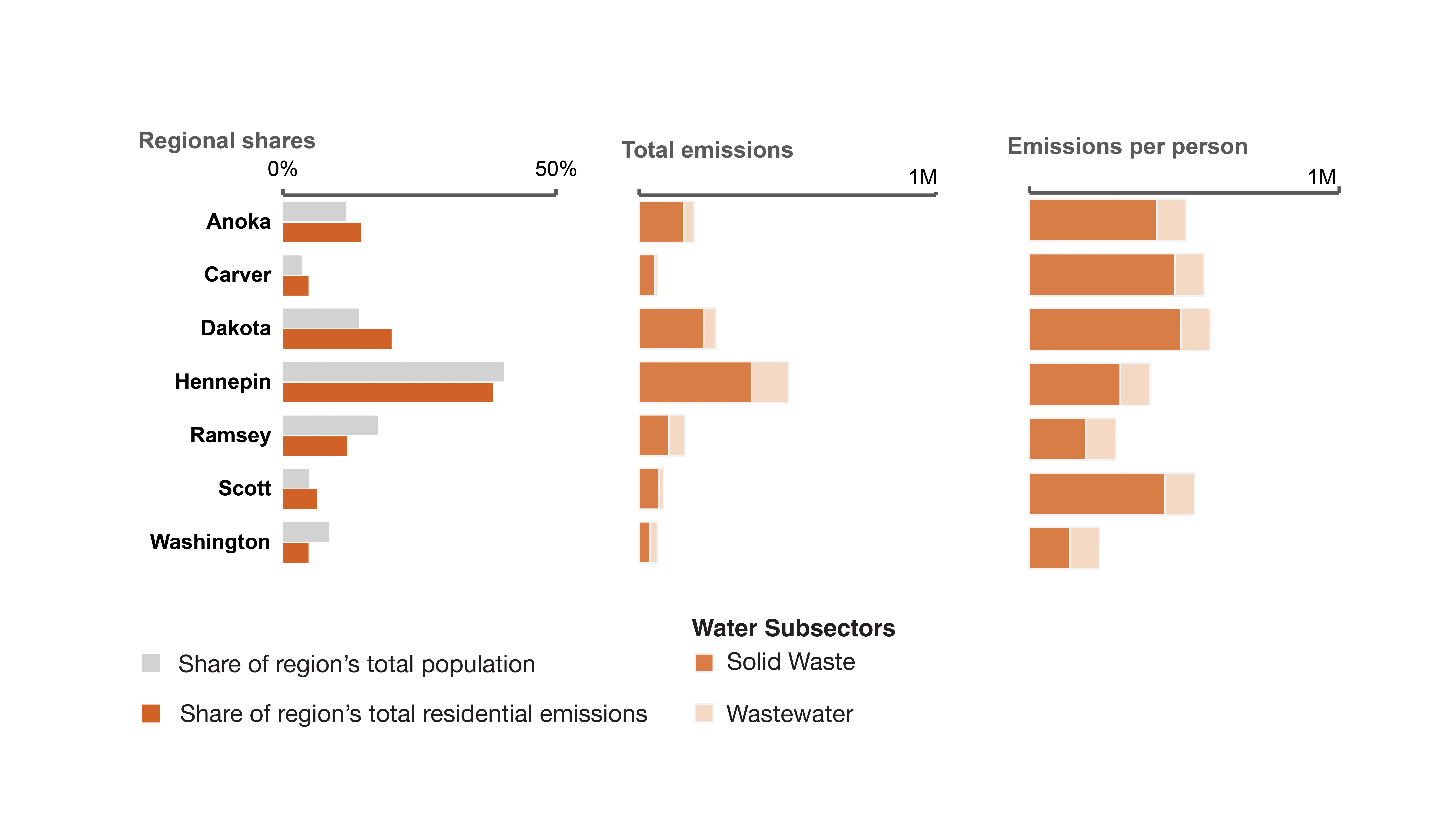

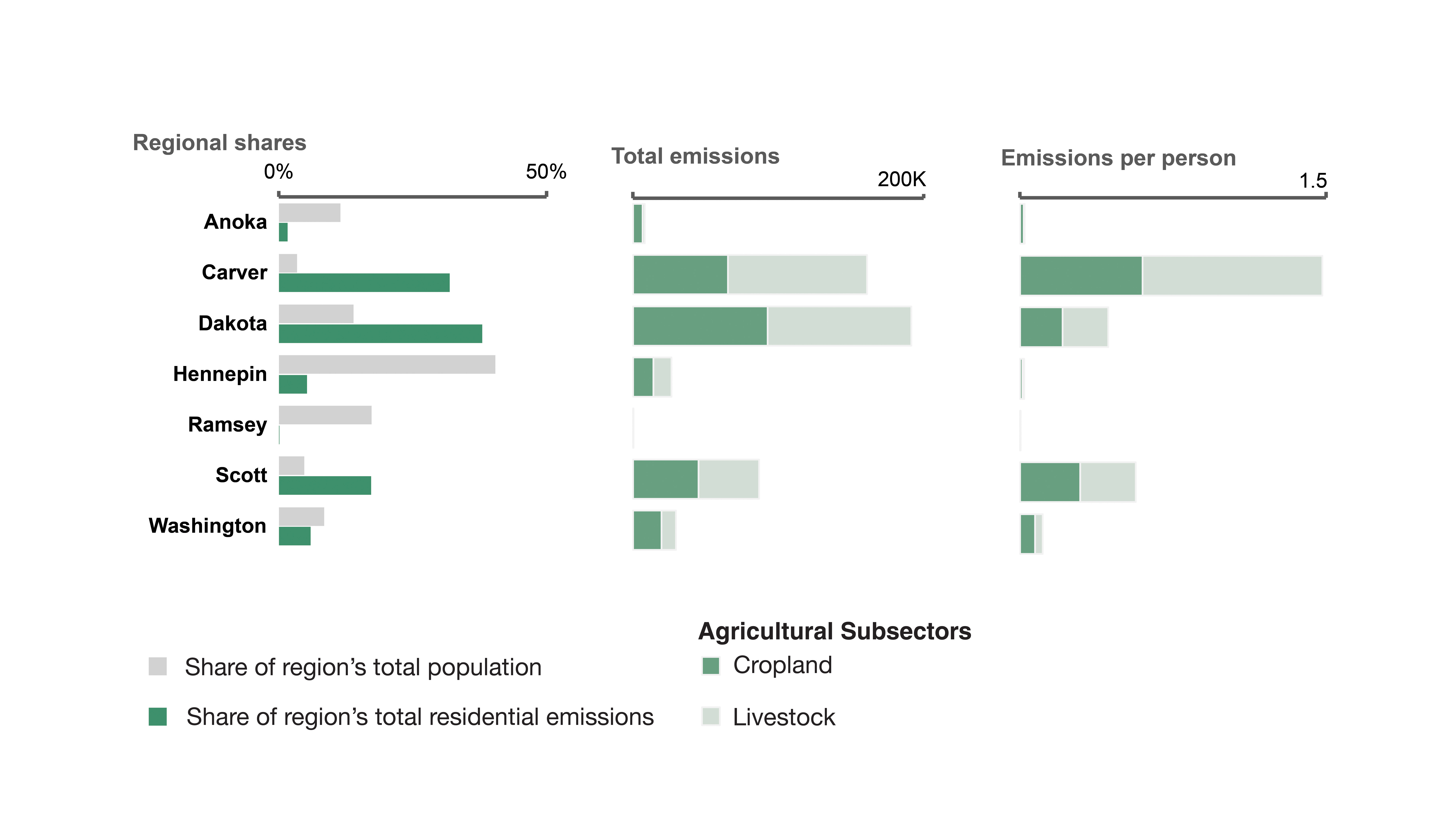

Regional greenhouse gas emissions

We protect and restore natural systems

Connection to climate change

Connection to American Indians and traditional knowledge

Connection to state efforts and Met Council roles

Risks and opportunities related to natural systems

Imagining and Planning for an Equitable and Resilient Future

When the Minnesota Legislature created the Metropolitan Council in the late 1960s, they were motivated by the conditions in the Twin Cities metro region to imagine a better, coordinated way forward. We were given the challenge to consider the long-term future of our communities as a whole. To effectively apply that long-term lens, we need to be able to imagine what is possible in the future.

While our region is thriving in many ways, we have also faced significant challenges in recent years, from the COVID-19 pandemic to civil unrest, and other social and economic changes. As we look out to 2050 and imagine the region we want to have, we need both the innovation and expectations that live in our imagination. Looking into the future and pairing that with the possibility of providing an equitable and resilient future for generations to come compels us to think creatively about how we get there. This plan, however, is far from imaginary. It is grounded in the policy and investment directions for the region’s future, with objectives to guide our specific work, and policies and actions to implement.

As directed by state law, the Met Council is responsible for preparing a comprehensive development guide for the seven-county metropolitan area. Imagine 2050 is the shared vision for the future of our region through 2050. While the Met Council is responsible for developing Imagine 2050 and plans for housing and the three statutory regional systems – wastewater, transportation, and regional parks – the vision in Imagine 2050 can only be accomplished through partnerships across the region with residents, local governments, nonprofit organizations, businesses, and philanthropic organizations.

Imagine 2050 tackles issues that are greater than any one neighborhood, city, township, or county alone can solve or address to reach the regional vision. Our region has tackled complex challenges in the past. This plan builds on our region’s past planning accomplishments and drives toward the regional vision with a focus on residents of the region, increased partnerships in the region, and integrated planning approaches across the Met Council’s responsibilities.

The role of regional planning

Under state statute, the Met Council is responsible for developing the comprehensive development guide:

The Metropolitan Council shall prepare and adopt, after appropriate study and such public hearings as may be necessary, a comprehensive development guide for the metropolitan area. It shall consist of a compilation of policy statements, goals, standards, programs, and maps prescribing guides for the orderly and economical development, public and private, of the metropolitan area. The comprehensive development guide must recognize and encompass physical, social, or economic needs of the metropolitan area and those future developments which will have an impact on the entire area including but not limited to such matters as land use, climate mitigation and adaptation, parks and open space land needs, the necessity for and location of airports, highways, transit facilities, public hospitals, libraries, schools, and other public buildings. (Minn. Stat. 473.145)

The Met Council develops a comprehensive development guide at least once a decade following the updates to the long-term forecasts that follow the decennial U.S. Census. Imagine 2050 encompasses the requirements of the comprehensive development guide as well as the policy and system plans. All of these elements were developed in coordination with one another in order to better align the regional planning efforts and realize opportunities to further advance regional goals. State statute defines three metropolitan systems plans:

- Transportation Policy Plan (Minn. Stat. 473.146)

- The development of the Transportation Policy Plan also is guided by federal transportation planning requirements.

- Water Policy Plan (Minn. Stat. 473.146 and 473.157)

- The Water Policy Plan also includes the Metropolitan Area Water Supply Plan (Minn. Stat. 473.1565)

- Regional Parks and Trails Policy Plan (Minn. Stat. 473.147)

In addition to the three statutory metropolitan systems plans, Imagine 2050 includes a Housing Policy Plan. The Housing Policy Plan provides an expanded policy framework to inform the Met Council’s review of the housing elements and housing implementation programs of local comprehensive plans required in statute (Minn. Stat. 473.859, subd. 2 and subd. 4) as well as direction for our housing-related programs.

Imagine 2050 assists local governments to create consistent, compatible, and coordinated local comprehensive plans that together advance local visions within the regional policy framework and help ensure efficient and cost-effective regional infrastructure. The Met Council reviews local comprehensive plans based on the requirements of the Metropolitan Land Planning Act, state and federal guidelines referenced in this document, and the policies contained in all chapters of the comprehensive development guide. The Met Council considers each local comprehensive plan’s compatibility with the plans of neighboring and affected jurisdictions, consistency with adopted Met Council policies, and conformance with metropolitan system plans.

If the Met Council finds that a community’s local comprehensive plan is more likely than not to have a substantial impact on or contain a substantial departure from metropolitan system plans, the Met Council can require the community to modify its local plan to assure conformance with the metropolitan system plans (Minn. Stat. 473.175)

How Imagine 2050 is organized

Imagine 2050 describes the region’s values and vision for 2050 and the goals, objectives, policies, and actions to achieve it, given the region’s existing conditions and emerging trends. Regional goals are broad directional statements that more specifically describe the desired end states for the region. These goals are shared across all policy and system plans included in Imagine 2050 (housing, land use, water, regional parks, and transportation).

Specific to each policy and system plan chapter are objectives, policies, and actions that together advance the shared regional goals and the regional vision. Objectives articulate the achievable results that advance each regional goal. Regional policies are the statements of intent and approach to regional issues or topics, independently and with partners. Policies are implemented through specific actions by the Council and partners.

How this plan works and relates to the other Met Council plans

While the Met Council has developed Imagine 2050 as a consolidated comprehensive development guide inclusive of the systems and policy plans, we recognize that different components of Imagine 2050 are required to be updated more frequently than the decennial planning process and that other amendments may be needed in policy plans from time to time. To that end, chapters of Imagine 2050 (for example, the 2050 Transportation Policy Plan) are intended to be independently updated and amended as required by the applicable state and federal statutes and following the procedures already established for them. Amendments to a chapter do not necessarily require amending the whole of Imagine 2050.

During the development of Imagine 2050, the Met Council convened an American Indian Advisory Council, described in greater detail elsewhere in this document. The Advisory Council created the paragraphs included here that acknowledge and describe the importance of the region’s land, water, and people to the Dakota people.

Dakota Makoce k’a Mni Okiciyaka

Dakota Land, Water, and People Acknowledgment

The seven-county region sits upon a creation site of the Dakota Oyate, where Mnisota Wakpa (Minnesota River) and Haha Wakpa (Mississippi River) converge on a sacred site called Bdote (where the rivers meet). Mni Sota Makoce (The Land of Mist), also known as Minnesota, holds immense significance as the origin of Dakota identity, languages, stewardship practices, and ways of life. For the Dakota people, there is not a separate creator and creation, a belief that is meaningfully encapsulated in the saying "Mitakuye Oyasin," which translates to "we are all related." This interconnectedness guides the original instructions the Dakota hold for the land, their traditions, and their place within the broader circle of existence. It is the spiritual source from which the Dakota Oyate originated and where they committed themselves to conserve, transmit, and steward their ancestral lands and ways of life for the next seven generations. For countless generations, Mni Sota Makoce has always been the primary identity shaper for the national character and life of the Dakota Oyate.

Land that makes up Minnesota is also the ancestral homelands of the Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, and the Ioway peoples. Violent settler-colonial policies – such as the passing of the Homestead Act, which facilitated the influx of settlers into these lands, and the 1863 Dakota Removal Act, which resulted in the systematic incarceration and forced displacement of most Dakota people from Minnesota – and other historical injustices and traumas inflicted upon the Tribal communities have had far-reaching and enduring impacts. Despite the legacy of genocide, the sovereignty of Tribal Nations and the right to exist as distinct Nations persist to this day.

The Metropolitan Council acknowledges that the land we currently call Minnesota, and specifically the seven-county region, is the ancestral homeland of the Dakota Oyate who are present and active contributors to our thriving region. The Metropolitan Council commits to address the unresolved legacy of genocide, dispossession, and settler colonialism and the fact that government institutions, including the Metropolitan Council, benefitted economically, politically, and institutionally after the forceable removal of the Dakota Oyate. The Metropolitan Council is dedicated to action – starting with the 2024 Land, Water, and People Commitments – to support the Dakota Oyate, the 11 federally recognized Dakota and Ojibwe Tribes in Minnesota, Ho-Chunk Nation, and the American Indian Communities representing over 150 diverse Tribal Nations that call the seven-county region home.

We are dedicated to ensuring a rights-based approach in our partnerships and decisions and promoting the well-being of the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations, as well as American Indian communities in the seven-county metro region. We will adhere to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and Minnesota Private Cemeteries Act, and actively pursue restoration of Dakota Lands where feasible, recognizing the importance of returning lands to their rightful stewards.

Landscape of the Region

Across nearly 3,000 square miles, centered around the confluence of three major rivers – Mississippi (Ȟaȟáwakpa / Wakpá Tháŋka), Minnesota (Mnísota Wakpá), and St. Croix (Hoǧáŋ Waŋká kiŋ) – live more than 3.2 million people who call the Twin Cities region home.1,2 Our mid-sized midwestern metro has much to offer the people who live, work, and play here.

The integration of our region’s built environment and natural systems is the foundation of a high quality of life valued by our residents, from new arrivals to multigenerational Minnesotans alike.3 From the clean waters above and below ground that make our lives, neighborhoods, and economy possible, to our nationally renowned parks and trails, our region’s diversity in landscapes and outdoor recreation is unique for a major metropolitan area and reflects a long history of thoughtful planning for growth and environmental stewardship.4

As a key road, rail, and air hub for the Upper Midwest, our regional transportation system is well-developed and reliable, with multimodal freight infrastructure, a highway system, and a growing public transit network. Since our last regional development guide was adopted in 2014, several major transit investments were completed: the METRO A, C, and D lines, our region’s first mixed-traffic bus rapid transit (BRT) lines, and our second light rail line, the METRO Green Line. Two additional transit projects – extensions of the METRO Blue and Green Lines – secured federal and local approvals. Not only does the regional transportation system facilitate our region’s strong and industry-diverse economy, but new transit infrastructure has sparked more housing development, particularly multifamily housing.5

Infrastructure and investments in our regional parks, wastewater, and transportation systems support vibrant and varied communities across the region, but it is the investments in our residents that create the greatest returns: Our strong regional economy is underpinned by state, county, and local funding of education, health care, and social services. Minnesota is nationally recognized for high levels of educational attainment and home to a considerable number of educational institutions, including 37 trade schools, colleges, and universities, which attract students from around the world. Minnesota often ranks above the national average for health care quality and costs, rates of insurance coverage, and health outcomes (despite large inequities by race, income, and disability status describe later).6,7 Lastly, the people of our region and state invest in themselves as well through strong civic engagement, such as high rates of volunteerism and voter turnout.8

The high quality of life in our region isn’t happenstance. It reflects a shared commitment to the betterment of our region even in the face of great challenges – perhaps especially so. The decades of partnership and a civic tradition of shared action by a variety of partners across the region have been foundational to the successes the region has achieved and equipped this region to successfully overcome challenges it has faced.

Underlying the civic tradition is the coordinated, regional planning approach that was at the heart of the establishment of the Metropolitan Council and further defined in the Metropolitan Land Planning Act. Community leaders then saw the value in collaboration to solve regional issues. As then Governor Harold LeVander noted, the Metropolitan Council “was conceived with the idea that we will be faced with more and more problems that will pay no heed to the boundary lines which mark the end of one community and the beginning of another.”

Through those partnerships, we were able to identify the most pressing regional issues and plan ahead – rather than react to – those issues. Our region has also been able to imagine the future we want to have and to deliver on that vision for a high quality of life and a world-class metropolitan area. Looking ahead, the Twin Cities region is uniquely positioned to build on our past successes and to take on the challenges of today and tomorrow.

One decade’s two eras: how our region has changed since 2014

The Twin Cities region had begun a definitive upswing in 2014, following years of economic turmoil resulting from the Great Recession. By September 2013, the region surpassed its previous peak employment, thanks in part to key industries of our economy.9 This period of economic expansion continued until early 2020. In 2012, median household income began to rise again for the first time since the recession began in 2008.10 However, heightened poverty and unemployment rates among the region’s Black and American Indian populations remained, widening inequities in economic well-being compared with the white population.11

Rapid multifamily development led new housing production overall.12 Most of these new units were built in urban areas, particularly Minneapolis, marking a shift in the region’s development patterns – prior to the recession, most new housing was built in suburbs and the developing edge of the region. Though increased housing production was sorely needed after years of standstill, the production of new affordable housing was only a small share of this new housing market activity and well below what was needed to serve our region’s current and future low- and moderate-income households.13 The lack of new affordable housing production, coupled with development pressures resulting in losses of naturally occurring affordable housing, slowly eroded housing stability.14

Not all trends are quantifiable: Narrative shifts in our regional conversation hold power, too. Between 2012 and 2014, the Met Council completed a federally required fair housing and equity assessment of the Twin Cities region. The report analyzed spatial patterns of race and income, and described how uneven access to different opportunities based on location reinforced our region’s large and persistent inequities by race and ethnicity across nearly all dimensions, from poverty to education to homeownership.15 During the public comment period of Thrive MSP 2040, Met Council was repeatedly called upon to turn the report’s findings into a commitment to use our influence as a regional planning agency and name equity as a regional outcome – and we did. As equity became part of local comprehensive plans and more deeply embedded into regional planning, policies, and investments, dialogue about equity matured from simply reciting present-day inequities to a more thorough look at root causes and systems.16

This momentum—here and everywhere else—was halted in March 2020 when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an outbreak of a new novel coronavirus (COVID-19) as a global pandemic.17

COVID-19 pandemic upends and reshapes our lives

Public health and peacetime emergencies orders were made at every level of government. Within weeks, stay-at-home mandates were issued, schools and universities closed, and nearly all areas of the U.S. economy shutdown to “flatten the curve” and “stop the spread.”

Job losses were staggering. In February 2020, the region’s economy was strong with just over two million jobs. Two months later, 283,000 fewer jobs were reported, a decline of 14%.18 The COVID-19 pandemic upended people’s everyday lives and four years later, many remain that way.

The health, economic, and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were extraordinary and touched every corner of our region. That they were largely borne by the region’s vulnerable and marginalized population groups was not. Like previous economic downturns, the pandemic simply made structural inequities across population groups in the Twin Cities region more visible. For example:

- American Indian, Black, and Latine communities experienced higher rates of COVID-19 infection and deaths, mirroring pre-existing racial disparities in overall health and health insurance coverage in Minnesota.19,20 People with disabilities, LGBTQ+ people, and people who lack housing stability or were unhoused also experienced elevated rates of COVID-19 infection relative to their share of the population.21 Older adults (over age 65) were far more likely to succumb to COVID-19, particularly those in long-term care facilities.22

- Workers of color and immigrant workers experienced the highest unemployment rates during the shutdowns. Though federal relief packages and expanded unemployment insurance benefits helped to offset some of the initial economic shock waves – temporarily reducing disparities in lost income by race and ethnicity – immigrant and refugee workers, especially undocumented workers, were not eligible.23,24

- People with disabilities have benefited from employers’ widespread adoption of remote work arrangements, as observed in increased labor force participation in Minnesota.25 At the same time, more people became disabled because of the pandemic.26,27

- Nationwide, young adults, people who identify as LGBTQ+, and people with disabilities were more likely to report heightened rates of anxiety and depression compared to pre-pandemic years.28

Not all impacts were as tangible as those described above; in fact, the pandemic brought physiological concepts such as “ambiguous loss” (a sense of grief, confusion, or anxiety that results from a loss that is unclear or lacks resolution) and Prolonged Grief Disorder (intense and persistent grief that interferes with daily life) into mainstream conversation.29,30 The simple fact is that everyone lost something, if not someone, in the pandemic. The impacts of such widespread grief are still unfolding for many individuals, within our communities, and across society at large.

As the COVID-19 pandemic compromised people’s lives and livelihoods, it also altered our daily interactions with our region’s built and natural systems. These trends were shared across large metros in the U.S. to varying degrees.31

COVID-19's lasting impacts on Minnesotans

- Nearly 2 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported across the State of Minnesota as of January 2025. Infection rates have largely mirrored already well-established health and health care inequities, with disproportionately higher rates among American Indian, Black, and Hispanic/Latine communities. Older adults, especially those living in long-term care or other institutional settings, also experienced heightened rates of infection and serious illness.

- Nearly 16,500 Minnesotans have lost their lives since the pandemic began, including 8,300 residing in our seven-country region.

- Over 238,000 COVID-related hospitalizations have taken place across Minnesota since the pandemic began, including 66,000 in the region.

- An estimated 365,000 adults in Minnesota may have experienced Long COVID symptoms, most commonly fatigue, trouble breathing, and brain fog.

Whether the result of a missed milestone, cancelled event, disruption of a job or schooling, the past four years had limitless ways of creating a sense of grief and loss, challenging our individual and collective resilience.

People spent more time outdoors for recreation, exercise, social gatherings, and mental health – a trend noted in various regional data. For instance, visits to our Regional Parks and Trails System considerably increased between 2021 and 2022.32 And, according to the Travel Behavior Inventory, walking as a mode of transportation was also up across most areas in the region between 2019 and 2021.33

Changes in people’s travel behavior and shifts in the transportation needs of businesses have impacted the regional transportation system in various ways. Many workers ended their daily commutes.34 In 2021, one in every nine of the region’s 2.8 million workers worked from home, a share that is largely consistent across the region’s seven counties.27F35F34F35 Once thought to be temporary, remote and hybrid work arrangements are shaping up to be a permanent feature of the post-COVID economy.36 For example, with less demand for trips to and from workplaces, the region’s public transit experienced significant losses in ridership. In 2021, region-wide transit ridership was about 42% of 2019 ridership.37,38 Even with less vehicle travel overall, traffic fatalities and serious injury crash rates in the Twin Cities metro increased in 2020 and 2021.39

Housing choices expanded for some households but narrowed for many during the pandemic. Lost and reduced income increased housing instability, especially for renters, who already had high rates of housing cost burden. Federal, state, and local authorities enacted protections such as eviction and foreclosure moratoriums, emergency rental assistance, and mortgage forbearance and loan modification programs to prevent widespread housing losses during the pandemic’s peak.40 Research suggests the effectiveness of these programs was mixed, however.41,42,43 Further, most housing protections ended sometime in 2021, despite only partial economic recovery and the still-high prevalence of COVID-19.44 In contrast, more financially secure households took advantage of historically low mortgage interest rates in 2020-21 to better align their housing situation with their household’s needs and preferences.45

Thirty-eight months after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the federal public health emergency expired – a new beginning that somehow also lacked a conclusive end. The first two years of the post-pandemic recovery (2023 and 2024) have ushered in new headwinds across U.S. metro areas including the tightening labor markets due to workforce shortages; rising consumer costs, especially in housing; and high vacancy rates and property value losses in office and commercial spaces, particularly in urban downtowns.46 While the challenges may not be unique, each metro area’s competitive advantages and limitations will inform their response and successes to overcoming these emergent issues.

Socially and environmentally, our region is changing

Our region’s reckoning with racism

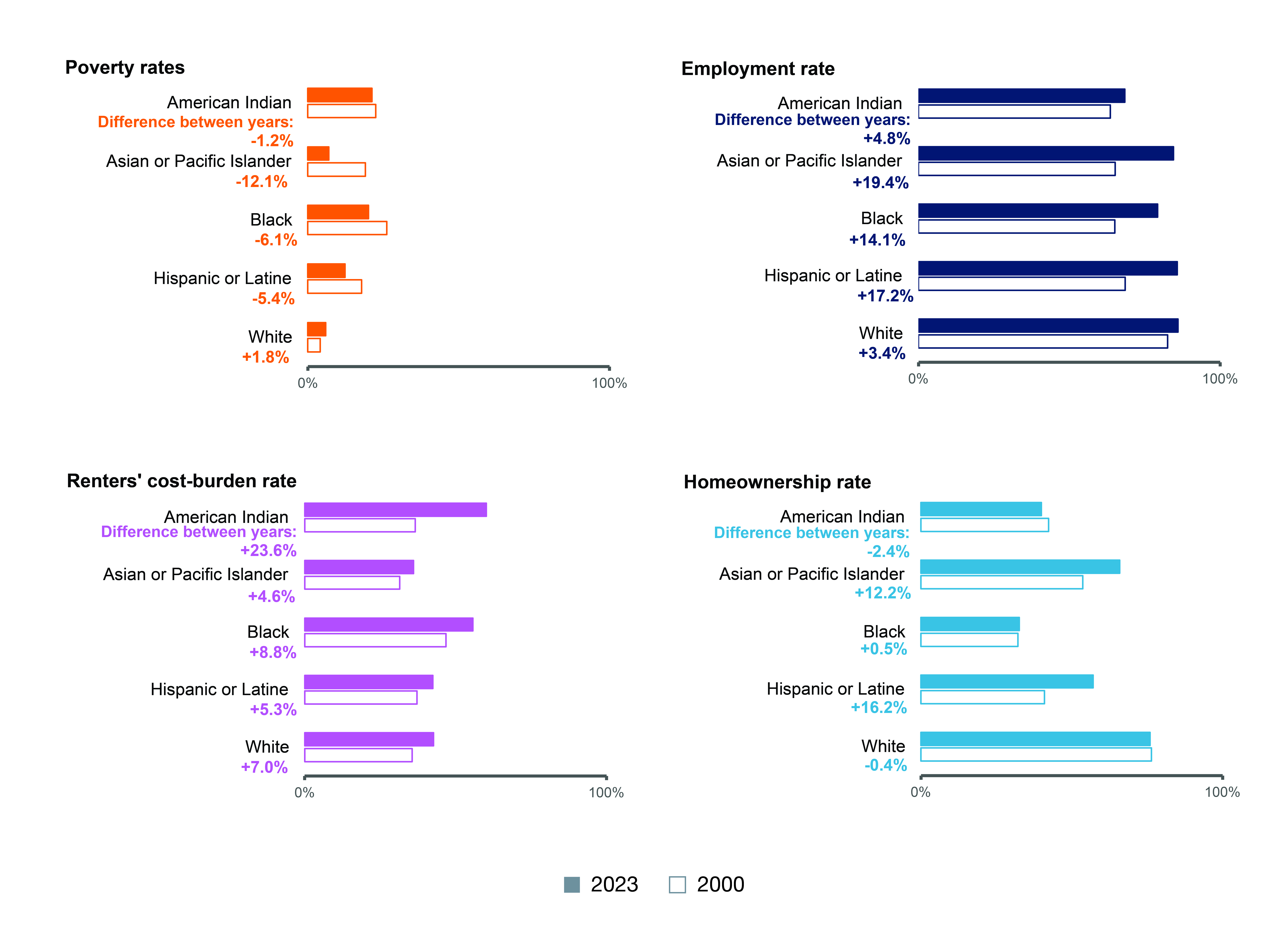

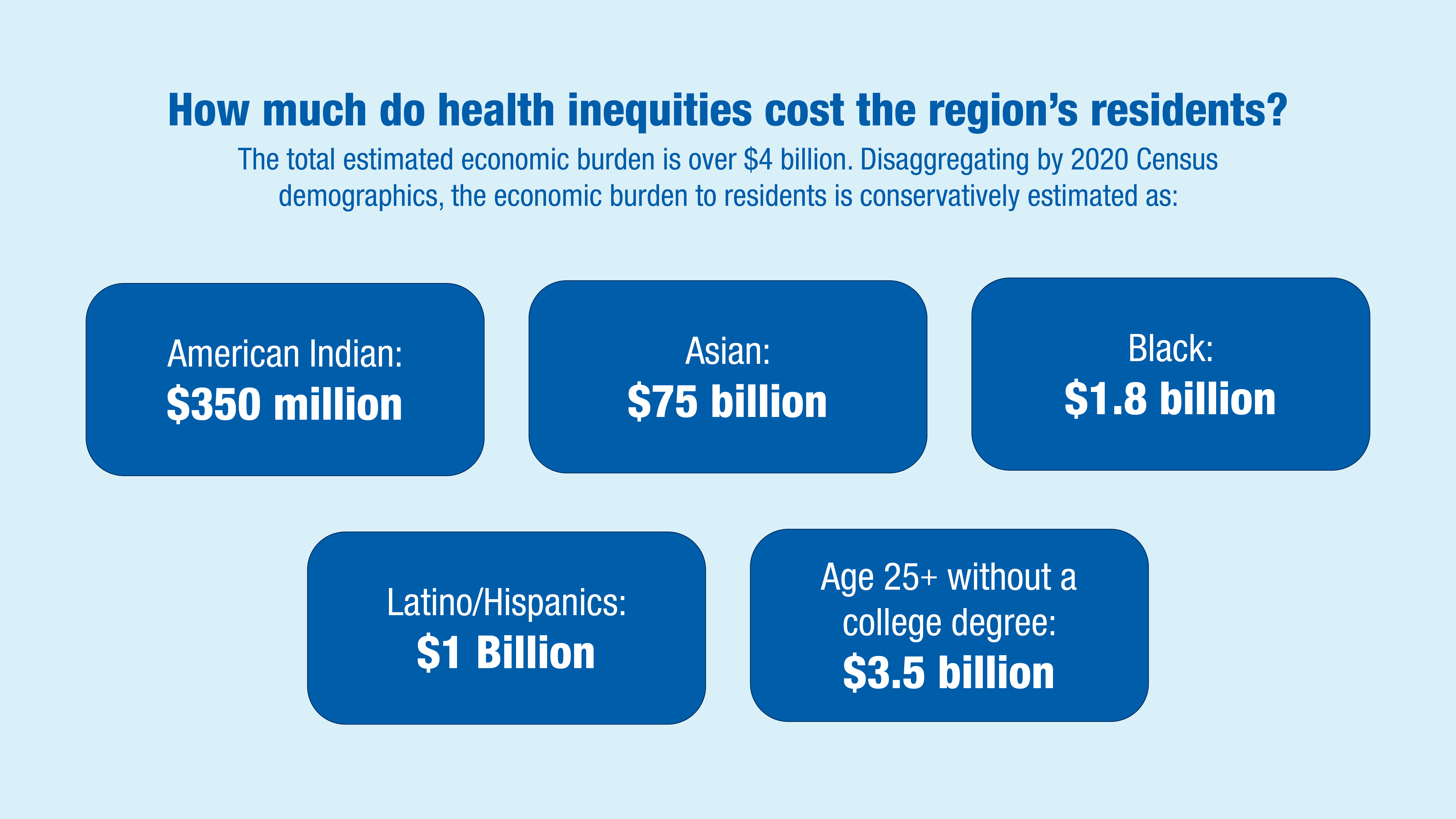

The COVID-19 pandemic was both an unprecedented event and a real-time case study of structural inequities in the U.S. healthcare system, economy, housing markets, and immigration systems. The disproportionately negative outcomes of the pandemic for low-income people, Black people, American Indians, people of color, people with disabilities, and immigrants and refugees in our region occurred precisely because the inequities pre-dated the crisis. These inequities, particularly by race and ethnicity, are—and have always been—our region’s most malignant pre-existing conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.1: Racial inequities in the Twin Cities Metro

Source: Metropolitan Council analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) One-Year Estimates, Summary Files and Public Use Microdata (ACS PUMS), 2000. 2022 and 2023. Data summarize the 15-county Minneapolis-Saint Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI metropolitan statistical area (MSA) as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

In 2020, the Twin Cities region faced significant challenges beyond the ongoing presence of a global pandemic. In May, following the death of George Floyd while in police custody, protests turned violent, and ultimately, both law enforcement officers from around the state, and the National Guard were called in to assist in restoring order. The four officers involved were immediately fired, ultimately charged criminally, and were sentenced to prison. The cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul experienced significant property damage, totaling more than $500 million, primarily along the Lake Street corridor, which was one of the most diverse commercial corridors in the region.

Concerns prompted a robust debate over the future of public safety and law enforcement locally, at the state level, and more broadly. Over the next few years, the Minneapolis Police Department lost about a third of its sworn officers to retirement, disability, transfers, and resignations, and as of 2024, staffing remained below the minimum required by city charter. Other police departments in the region, including the Metro Transit Police Department, have struggled to meet their staffing goals since then.

The entire region experienced the impact of overlapping community crises occurring within the same calendar year. Homicides increased 58% in Minnesota between 2019 and 2020. The increase in homicides in the city of Minneapolis was even greater, at 77% year over year. As of 2023, the homicide rate remained well above pre-COVID numbers, although overall crime numbers have been decreasing and returning to a pattern more in alignment with pre-pandemic levels.47

Increases in crime disproportionately impacted Black residents. According to City of Minneapolis data, in 2021, 83% of shooting victims were Black and 89% of suspects with descriptions were Black. In 2021, there was 1 Black shooting victim for every 150 black residents of Minneapolis, with 1 white shooting victim for every 3,768 white residents.48

These recent, history-shaping events highlighted disparate experiences of residents across the Twin Cities region, while also fitting into longstanding patterns within data sets that demonstrate ongoing and persistent racial disparities within regional systems and structures that touch on many aspects of a resident’s daily life. Beyond outcomes-based data, additional data points highlight how discrimination, and its resulting harms are experienced by people of color, ethnic groups, and immigrants.

According to a 2021 statewide survey about experiences with discrimination, 64% of American Indians and 60% of Black adults surveyed said have been called a racial or ethnic slur by someone in Minnesota.49 The same was true for 53% of Hmong and 49% of Latine respondents. Nearly half of adult children of immigrants (49%) also reported this experience. Other findings from the study reveal high rates of perceived and experienced discrimination in employment, policing, and housing that vary across racial or ethnic group but that are consistently high for the Black adults and American Indians surveyed.

The Twin Cities region will need to continue to grapple with and address the acute and broad impacts of racism and discrimination to eliminate existing headwinds to growth, opportunity, and prosperity in the years ahead. What will emerge from a period of pandemic impacts, civil unrest, and overall societal instability remains to be seen. Individuals and communities are adjusting to and recovering from the health and societal changes wrought by COVID-19. The Minneapolis Police Department is now under a consent decree with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights and a consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice, and a memorial at the site of George Floyd’s murder is currently under development.

At an outcomes level, recent health and economic data do not show meaningfully better outcomes toward racial and health equity than in past years. Across measures such as housing instability, life expectancy, household wealth, access to healthy food, and educational attainment, race remains the most predictive statistical factor in projecting likely outcomes for a resident of the Twin Cities region. Until race is no longer a predictive factor across the region, work remains in the effort to build an equitable, prosperous, and inclusive community in which every resident is valued and can thrive.

We live in a warming, wetter region

Evidence of climate change clearly exists within our region today, and climate impacts are expected to increase and intensify. According to a 2022 survey conducted by the University of Minnesota, 76% of Minnesotans are concerned about climate change, especially youth and young adults.50 The recent summer days filled with wildfire smoke (2021) and a virtually snow- and ice-free winter (2023) are harder to ignore than slower-developing trends, but regional data show that we are already experiencing climate hazards and the human and economic costs associated with these changes.

Temperatures are rising, warming our winters and adding more days of extreme heat and drought events. Between 1895 and 2023, the region warmed 2.5 degrees F.51 The average daily minimum winter temperatures have increased 4 degrees F, and 6 of the 10 warmest winters have occurred since 2000.52 With warmer winter temperatures comes more freeze/thaw cycles, which can be hard on roads and other infrastructure. More frequent freeze/thaw cycles cause an increase in the use of deicing salt, adding additional strain to stormwater and wastewater infrastructure and contamination to groundwater and surface water.53 Warming is not limited to winters: our region has experienced eight days of heat over 100 degrees F since 1990, with projections of more days dangerously high temperatures in the next 50 years.54,55 Extreme heat is dangerous to people and natural systems and has economic ripple effects as it makes outdoor work unsafe and damages infrastructure over time.

Since 1895, average annual precipitation in the Twin Cities Region has increased by 4.7 inches.56 More recently, the region experienced the equivalent of seven years of rainfall between 2014 and 2019, a five-year period. Long-term observations have shown a dramatic increase in major rainstorms in Minnesota and are projected to keep increasing.57 Major rainstorms – including extreme flooding events – overflow surface waters (such as lakes and rivers), then oversaturate soil to the point it cannot absorb additional water and the region’s stormwater systems cannot keep up.58 Flooding poses a further threat to the region’s waters, as pollutants from the surface may either runoff into our waterways or concentrate and contaminate shallow drinking water supplies.

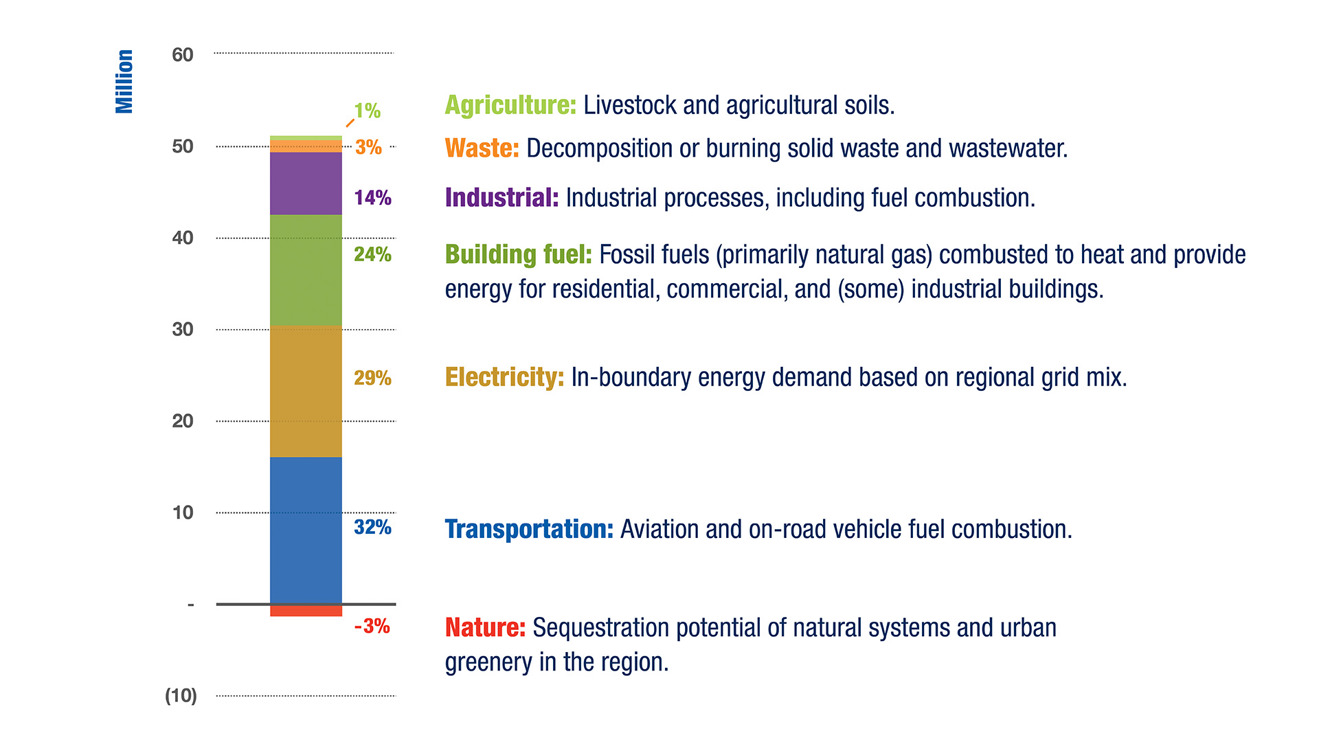

Human activities have accelerated the levels of greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, which drives climate change. In 2021, with over half of the state’s population, the seven-county region was responsible for approximately 33% of the state of Minnesota’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

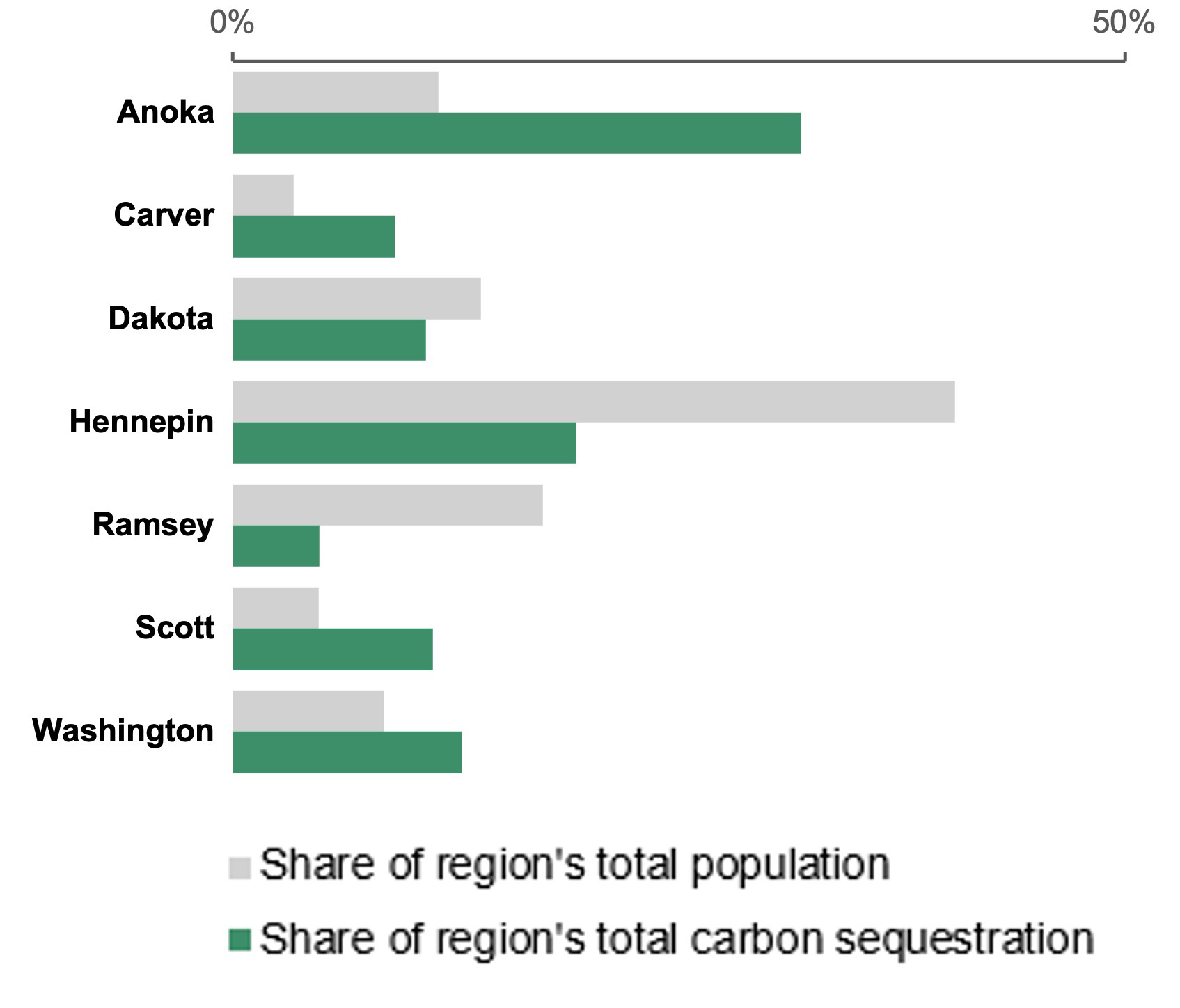

The region’s greenhouse gas emissions come from diverse sources, ranging from powering our workplaces, to heating our homes, to driving vehicles (Figure 2). Healthy natural systems can offset emissions through carbon sequestration and stocks.

Figure 1.2: Sources of region’s greenhouse gas emissions (in metric tons of CO2e) in 2021

Source: Metropolitan Council analysis of state, federal, utility, and scientific sources of sector data.

The impacts of climate change will not equally affect the people of our region, our built and natural systems, or areas of our economy. The regional goals and policy areas of Imagine 2050 describe this in more detail.

The people of our region

Indigenous people are the first people of this land. The land we all occupy in the seven-county Twin Cities region is historic Dakota land. More than 10,000 years before European and British North, the Dakota had developed an extensive communal society and held deep connections to the land and waters, which remain sacred sites and areas of significance today.59 The Dakota – and Ojibwe, who later migrated to the region and built alliances with the Dakota before external pressures created conflict – faced violent removal and genocide at the hands of early European settlers in the 1800s.60 The federal government continued the physical displacement of American Indians and advanced their cultural erosion through broken treaties and policies of assimilation through the end of the 20th century. Despite these gross injustices, 72,000 American Indians live the Twin Cities region today.61

Immigrants drove region’s early population growth—and will again

The same policies that forcibly removed American Indian populations created pathways for white immigrants to claim their lands.62 First British, then Swedish, Norwegian, and German immigrants arrived followed by Jewish, Italian, and Irish people. By the 1890s, nearly half (40%) of the state’s population were (predominately white) foreign-born immigrants, a much higher share than the U.S. overall at that point in history.63

The 20th and 21st centuries brought more racially diverse immigrants to the state and region. Chinese Americans and immigrants began moving to Minnesota as an alternative to growing hostilities on the West Coast. Fifty years later, 350 Japanese Americans, who had been forced into concentration camps established by the U.S. government at the start of World War II, were resettled in Saint Paul.64 Southeast Asian refugees, including Hmong, Laotian, and Vietnamese people, began arriving in the mid-1970s, fleeing increasing political instability and war.65 During this period, Mexican immigrants came to the Saint Paul’s East Side and West Side neighborhoods seeking economic opportunities created by labor force shortages; when these jobs dried up, some were targeted for deportation. In the 1990s, Somali refugees and immigrants established a large community in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis.66 Every immigrant group has contributed to the vibrant cultural fabric of our region.

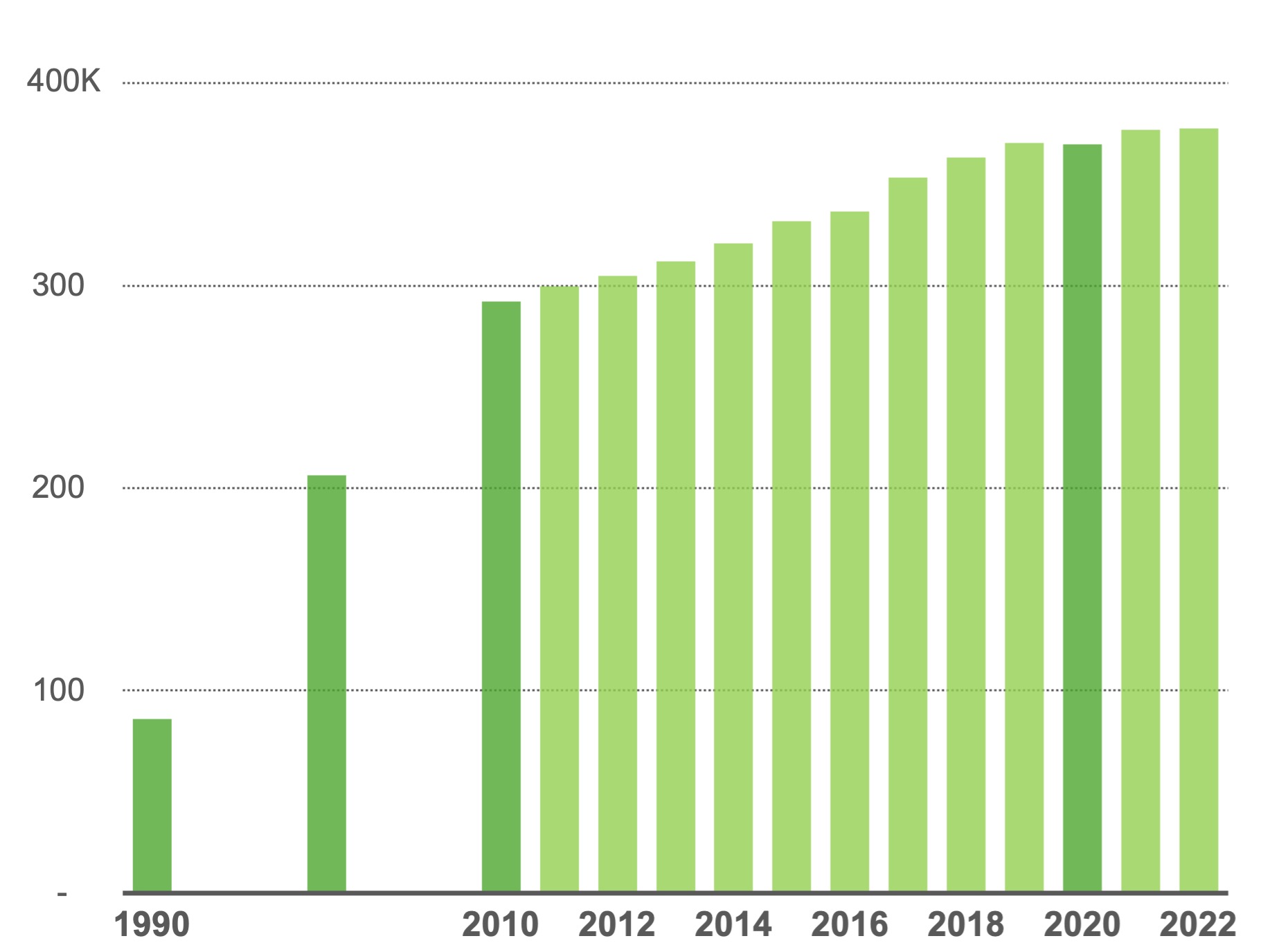

Immigration will continue to play an important role in future population and economic growth. Today over 377,000 immigrants live in the Twin Cities region, which is about one in every eight residents (Figure 3). The pace of immigration slowed down in the 2000s, and again in the 2010s, though immigration growth rates still outpaced overall population growth in those periods. In the 2020s, the region’s immigration and population growth rates are equal so far at 2%. The city of Saint Paul has the highest share of immigrants relative to their population, closely followed by Minneapolis, and suburban Hennepin and Ramsey counties.

Figure 1.3: Recent immigration trends in the Twin Cities region

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, five-year estimates (2011-2022).

Immigration will continue to play an important role in future population and economic growth. The region is expected to add approximately 311,000 immigrants between 2020 and 2050.67 In fact, immigration alone will account for nearly half (47%) of the region’s forecasted population growth to 2050.

Our population will grow and demographically transform by 2050

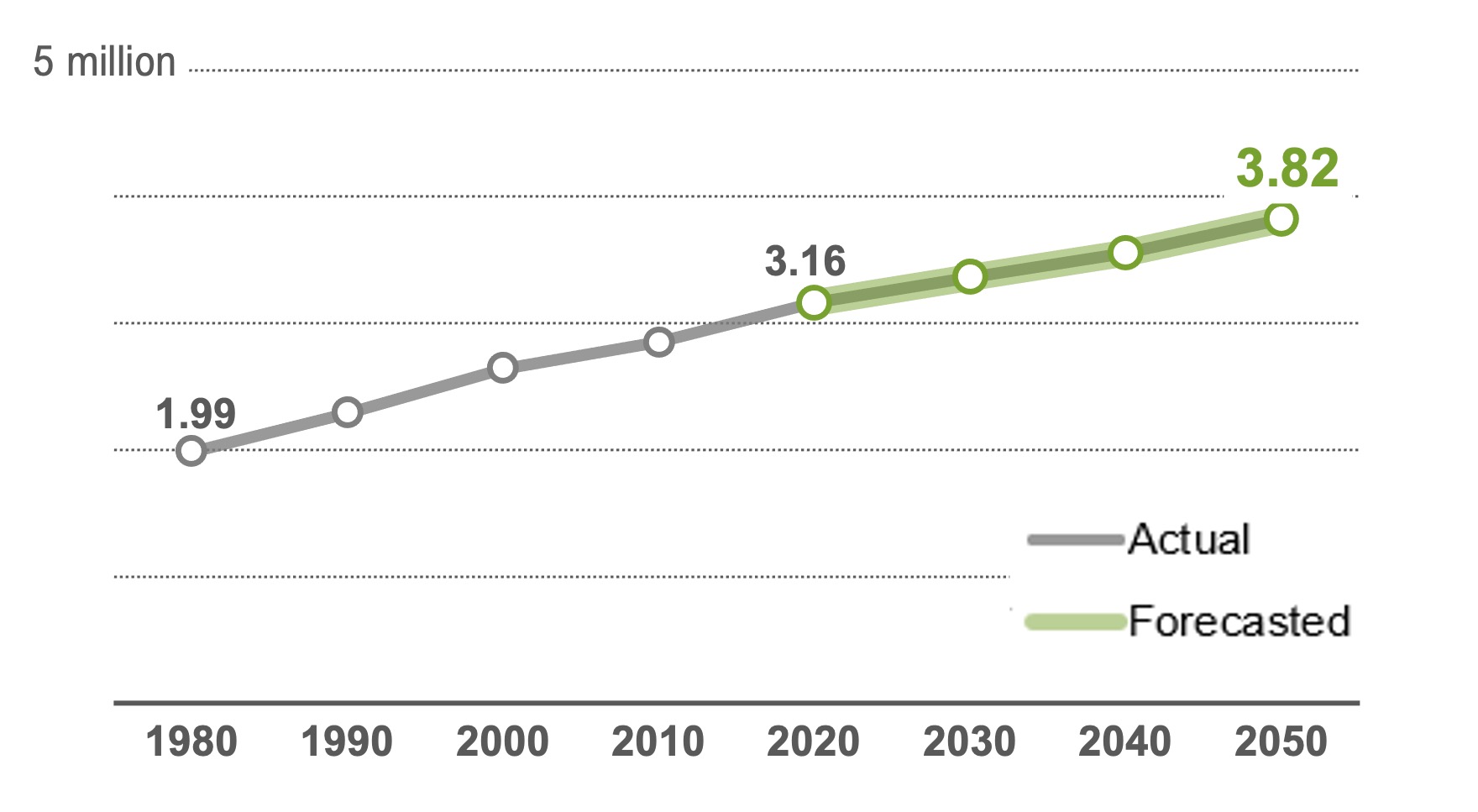

Today, the seven-county Twin Cities region is home to 3.2 million residents.68 The region’s population growth since 1990 was robust at 38%, outpacing the state of Minnesota (30%) and the U.S. (33%) over the same period (Figure 4). There is more population growth to come over the next 30 years: Met Council’s regional forecast shows a gain of 657,000 residents by 2050, an increase of 21%.

Regional population growth is the result of natural growth (that is, more births than deaths) and net migration (more people move to the region than leave). Natural growth will account for just over half (52%) of the region’s forecasted population to 2050.69 However, more people will leave the region than arrive from other parts in the state or U.S. in the 2020s and 2030s. This trend will reverse in the 2040s but not enough to overcome the earlier losses.70 Without immigration levels like the 1990s and 2000s, growth will stagnate.

Figure 1.4: Population in the Twin Cities region forecasted to 2050

Source: Metropolitan Council regional forecast (April 2023).

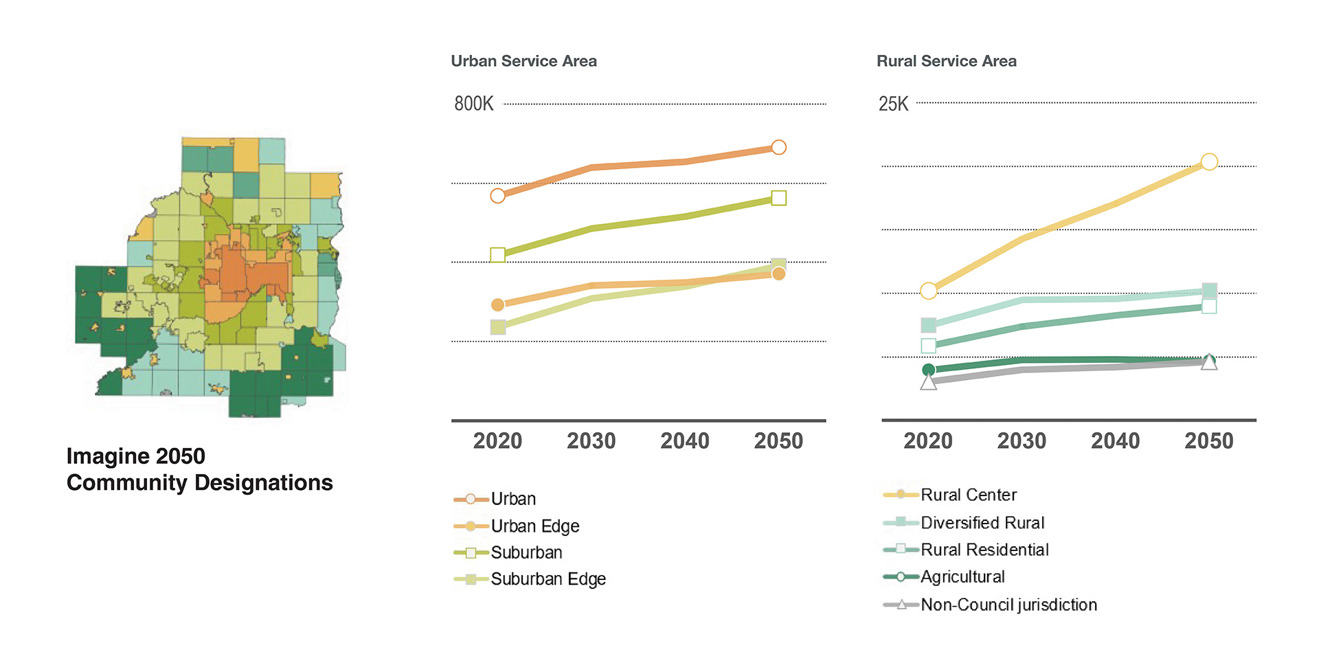

Future population growth will take place across the region. Met Council uses a real estate market and travel-demand model to forecast where this growth occurs at the local level.71 Mainly, forecasts consider location characteristics and amenities, economic growth, travel patterns, and access to destinations. Local forecasts were prepared in 2024 and reviewed by local governments; final local forecasts are adopted with Imagine 2050.

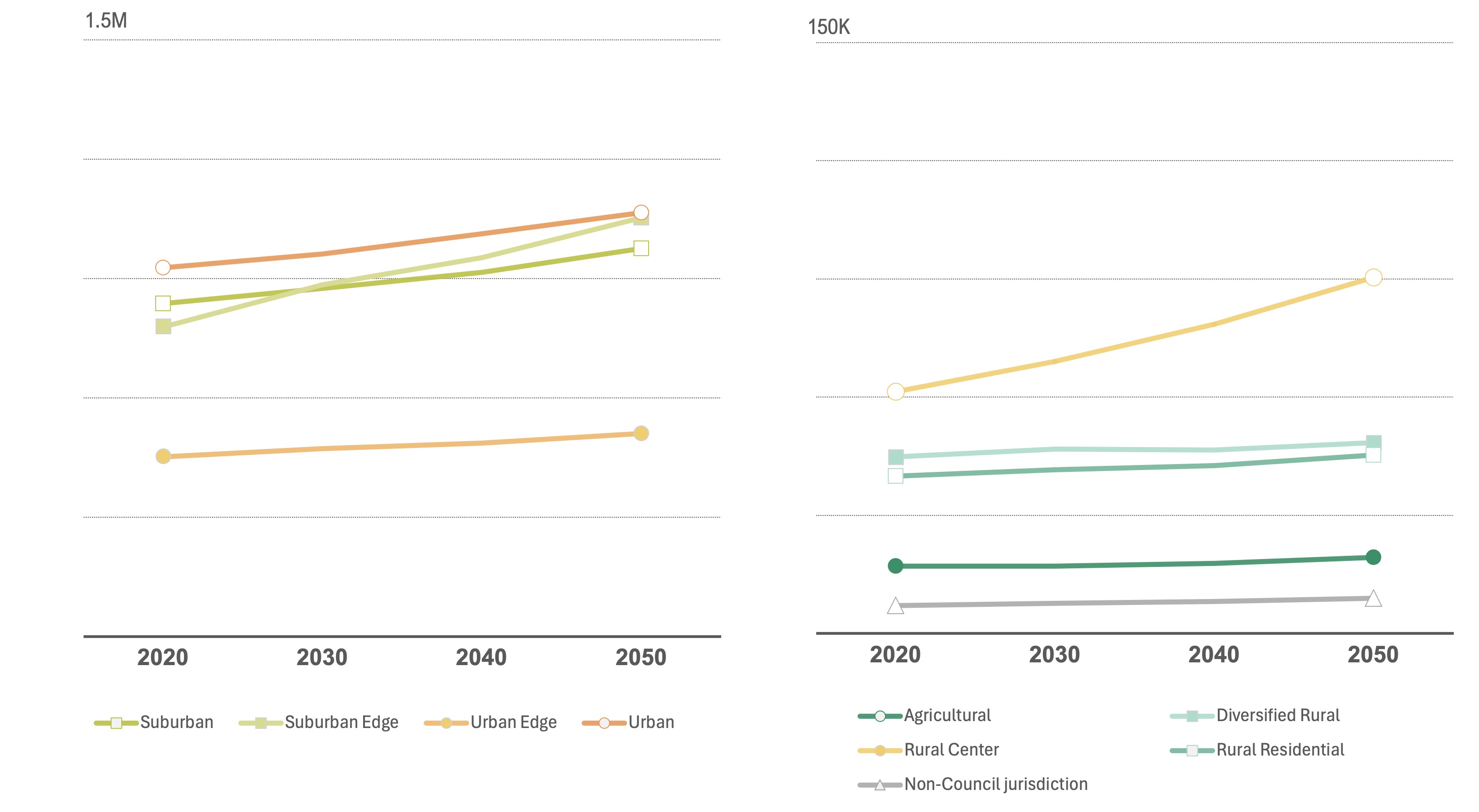

Growth will occur in all areas of the region (Figure 5). The region’s Suburban Edge communities will add the largest numbers of residents between 2020 and 2050 (273,000) and will experience the fastest rate of growth (35%). Suburban designated communities will add 138,000 residents (16% growth). Urban communities will grow mainly through redevelopment and infill and will add 139,000 residents (15% growth). Urban Edge communities will add 58,000 residents (13% growth). Rural communities (which includes Rural Centers) will add 42,000 residents (25% growth).

We can also think about the additional 657,000 residents the region will gain between 2020 and 2050 and how they will be distributed across the region. Suburban Edge and Suburban communities will account for most of the region's population growth: 42% and 21%, respectively. Urban and Urban Edge communities will account for 21% and 9% of population growth. The remainder of the region's growth, over 6%, will be in Rural communities.

The local forecasts show Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Eden Prairie, Lakeville, Blaine, and Maple Grove as the six cities gaining at least 20,000 residents between 2020 and 2050.72 For the most part, the region’s top 10 largest cities in 2020 remain so in 2050, with minor shuffling.

Figure 1.5: Forecasted population growth by Imagine 2050 Community Designations

Source: Metropolitan Council local forecasts (January 2025). See Community Designations in Land Use Policy chapter for more description on what those designations are and the places they describe.

Our region is the most racially diverse we’ve ever been, and the trend will continue

As of 2020, 31% of the region’s population is Black, American Indian, and people of color – up nearly four times their share in 1990 (8.4%).73 People who identify as multiracial had the highest relative growth between 1990 and 2020, followed by Latine people (+517%), Asian people (+304%) and Black people (+268%).74 The region’s white population increased 3.8% over this period, trailing American Indians at 5.3%. White residents remained the largest overall share of the population at 68.8% in 2020. Worth noting is that increasing racial diversity is happening everywhere in our region.

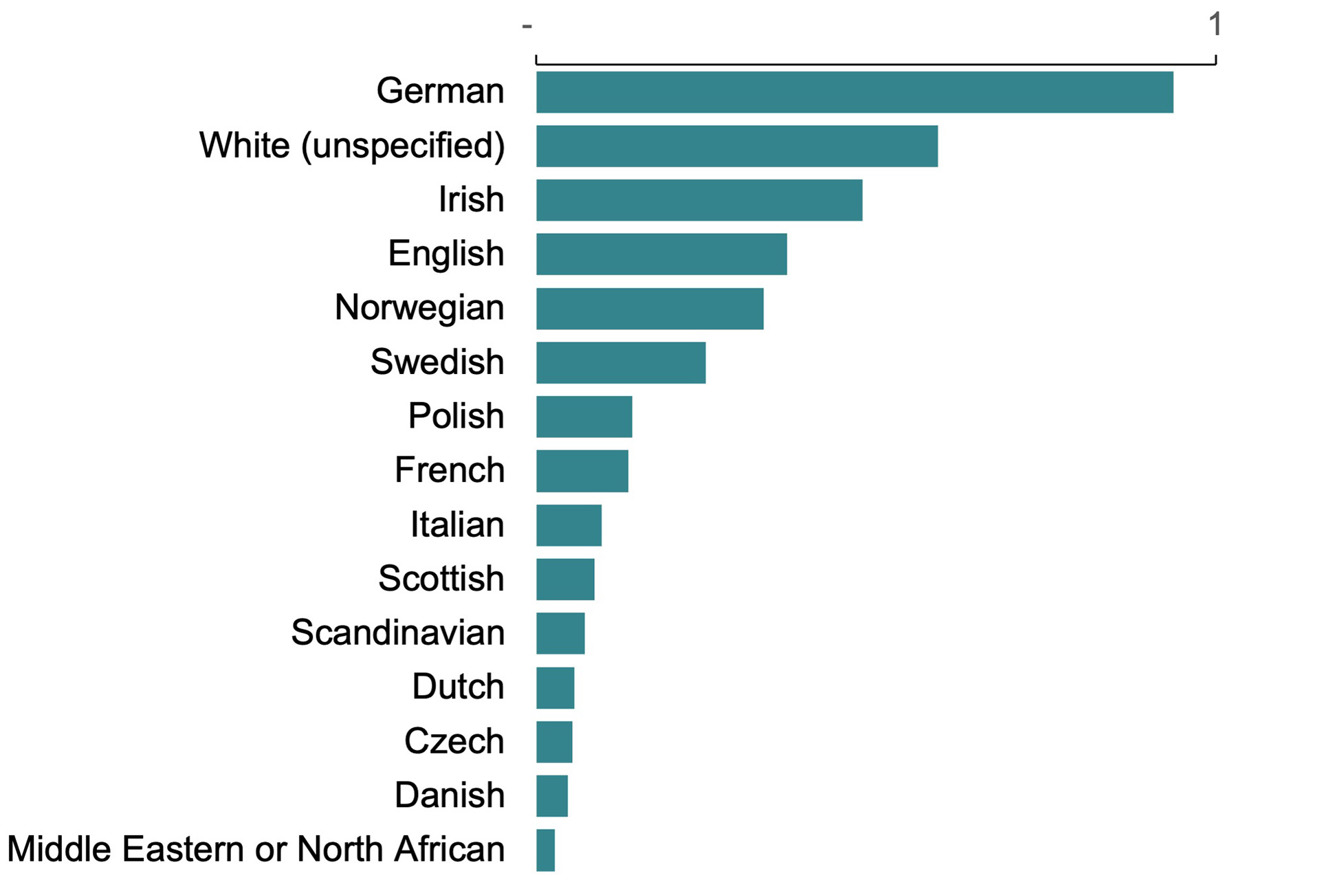

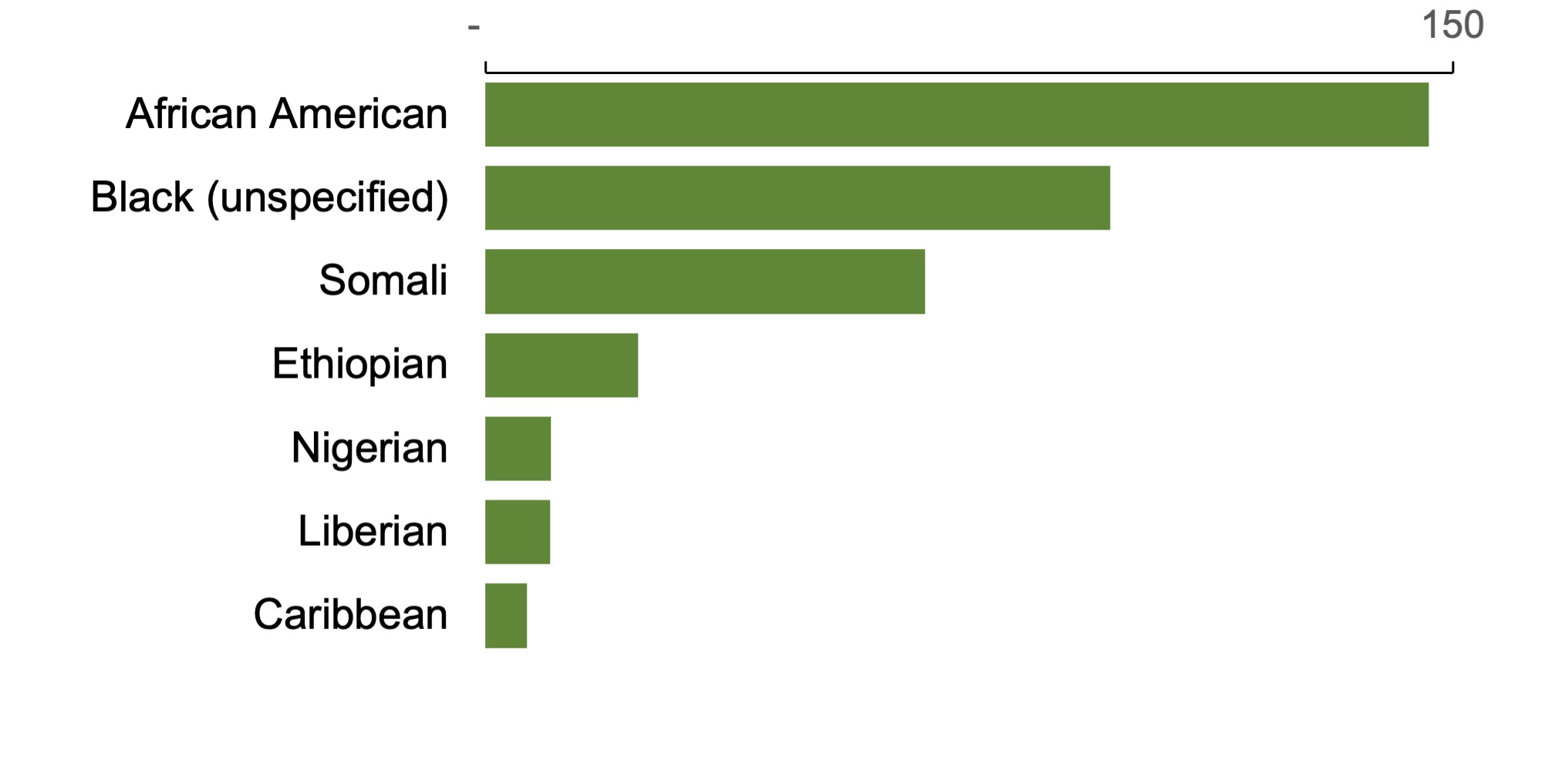

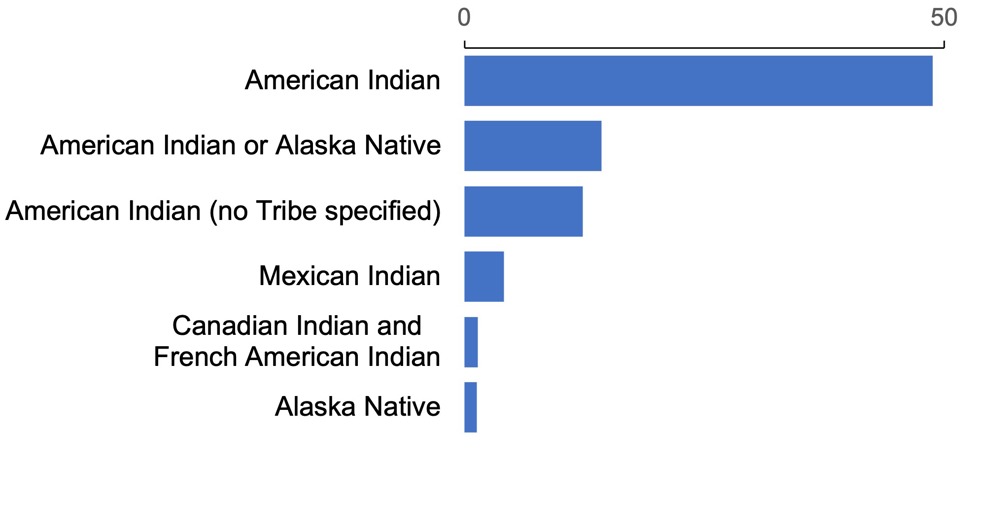

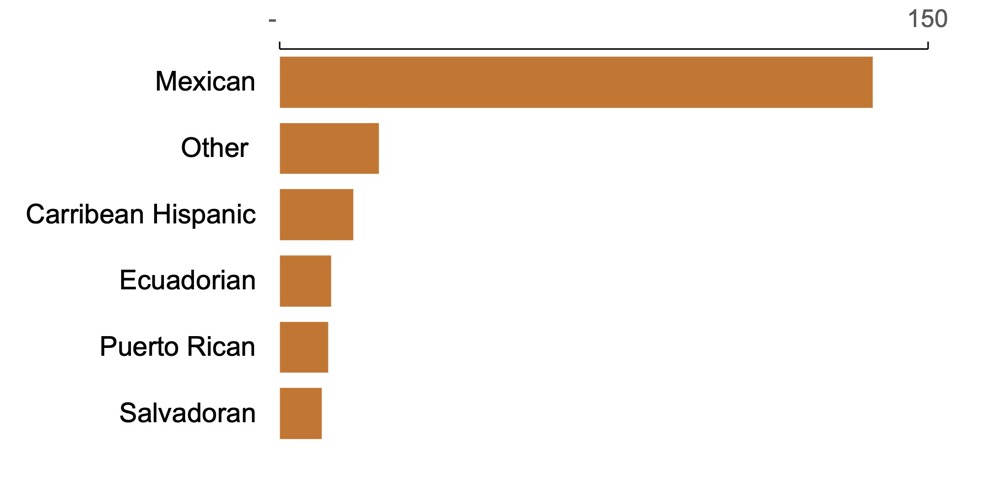

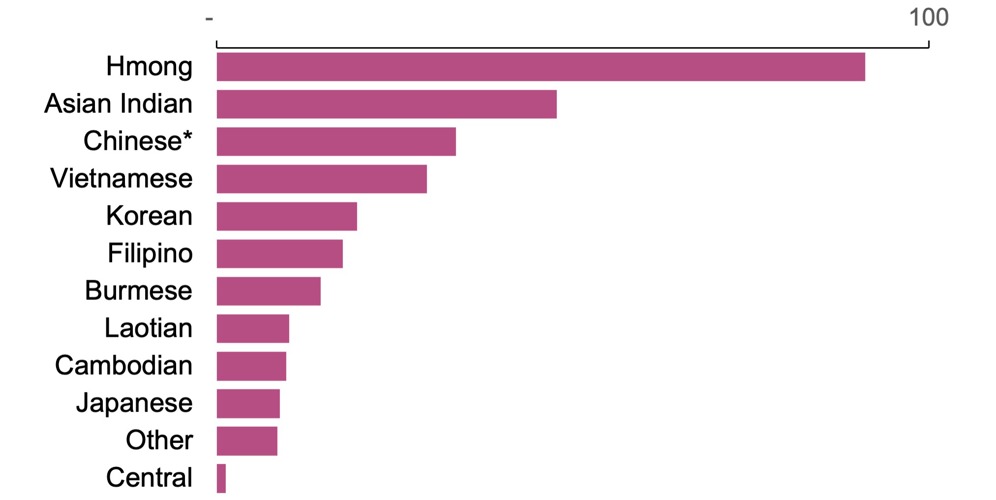

Though federally defined race and ethnic groups can be useful for tracking trends, they neither reflect the full diversity, lived experiences, or preferred identification of the people they are meant to describe. More detailed data released with the 2020 decennial census provides a more complete picture of cultural groups in the region. As Figure 6 shows, many of the immigrant groups described earlier remain well-represented in today’s population.

Figure 1.6: Snapshot of the region’s population in 2020 by detailed race and ethnicity groups

White groups

Black groups

American Indian groups

Hispanic/Latine groups

Asian groups

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census (Detailed Demographic & Housing Characteristics File A). Note: Numbers reflect all people who identified with this group, regardless of whether they also identified with other groups. Only groups with 1,000 or more people are included.

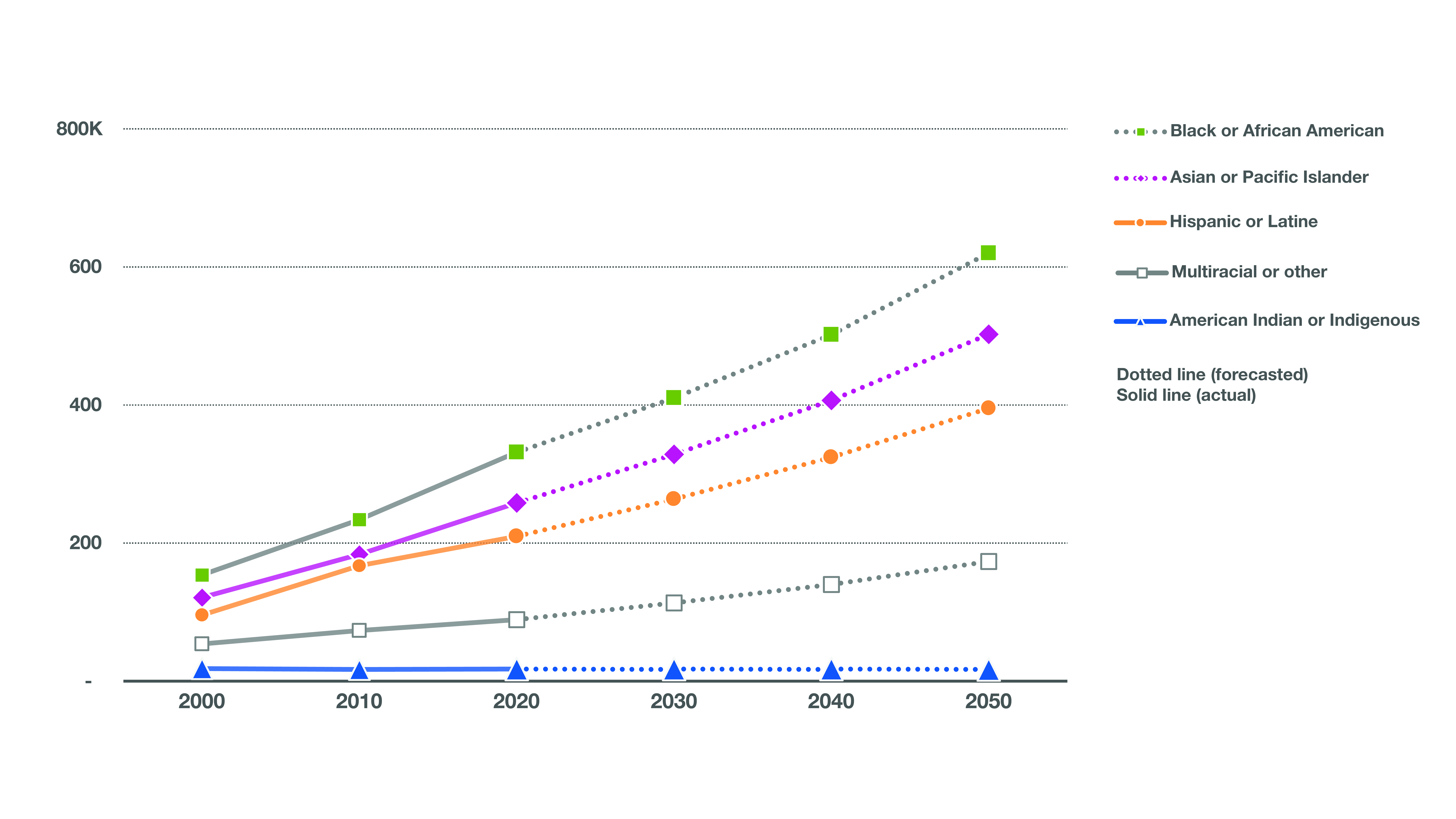

By 2050, nearly half (45%) of our region’s population will be Black, American Indian, and people of color, up from 29% in 2020 (Figure 7). Black and Asian communities will gain the most residents by 2050, followed by Latine and multiracial communities. The American Indian community is forecasted as stable to 2050, without growth, and the white population will level off and decline.

Figure 1.7: Forecasted population growth by race and ethnicity

Source: Metropolitan Council regional forecast (April 2023).

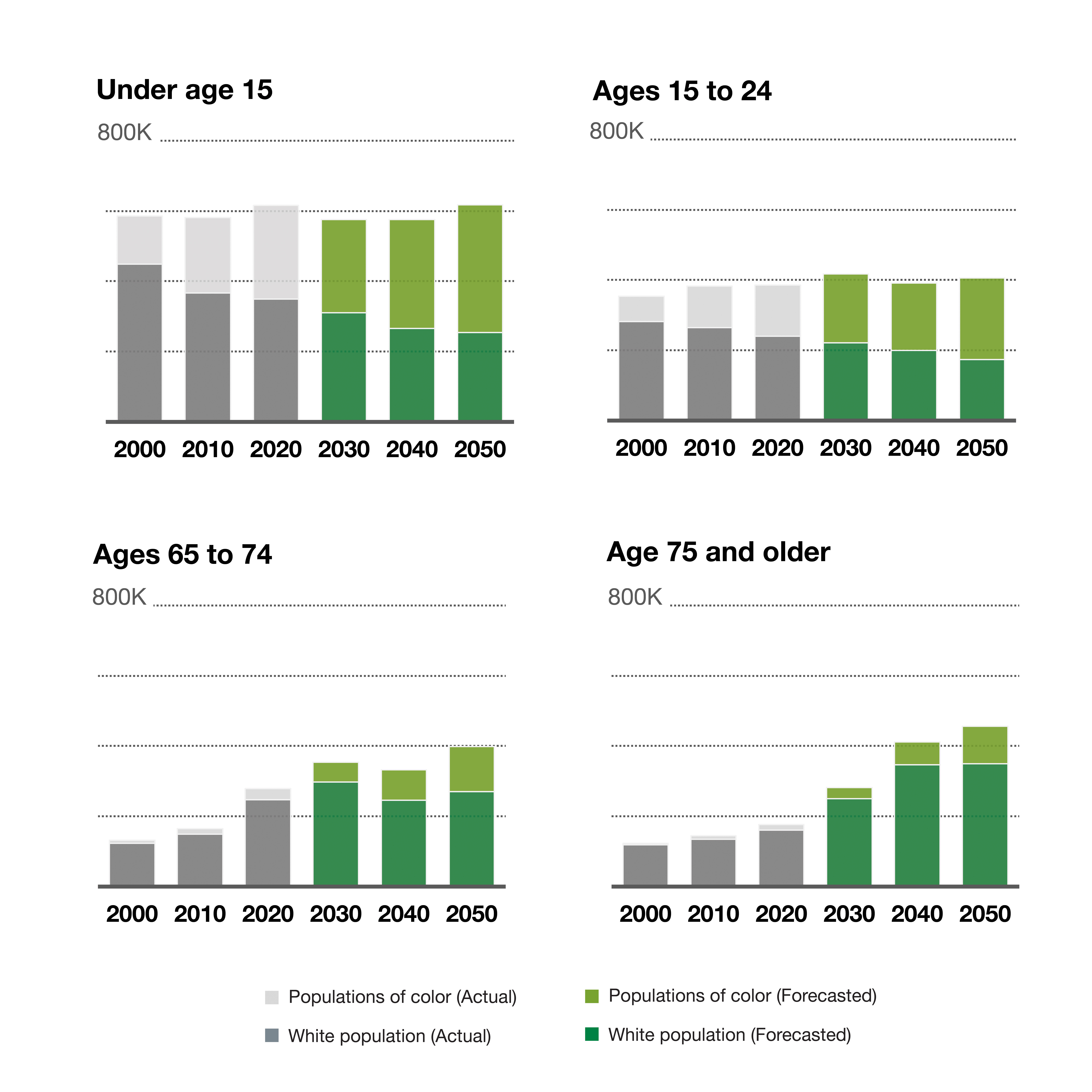

Simultaneously, our region – like the U.S. overall – is aging. The median age across the region’s population in 1990 was 31.7 years old; by 2020 it was 37.3. By 2050, the share of the region’s population over age 65 will nearly double, going from 14% in 2020 to 22% by 2050.75

More specifically, the white population composition is aging faster than other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 8). The share of youth and young adults that are Black, American Indian, and people of color will exceed the proportion of white youth and young adults by 2040. The prime workforce ages of 25 to 64 will be an almost equal share, while older adults are, and will continue to be, predominantly white.

Figure 1.8: Forecasted population growth by race, ethnicity, and age group

Source: Metropolitan Council regional forecast (April 2023).

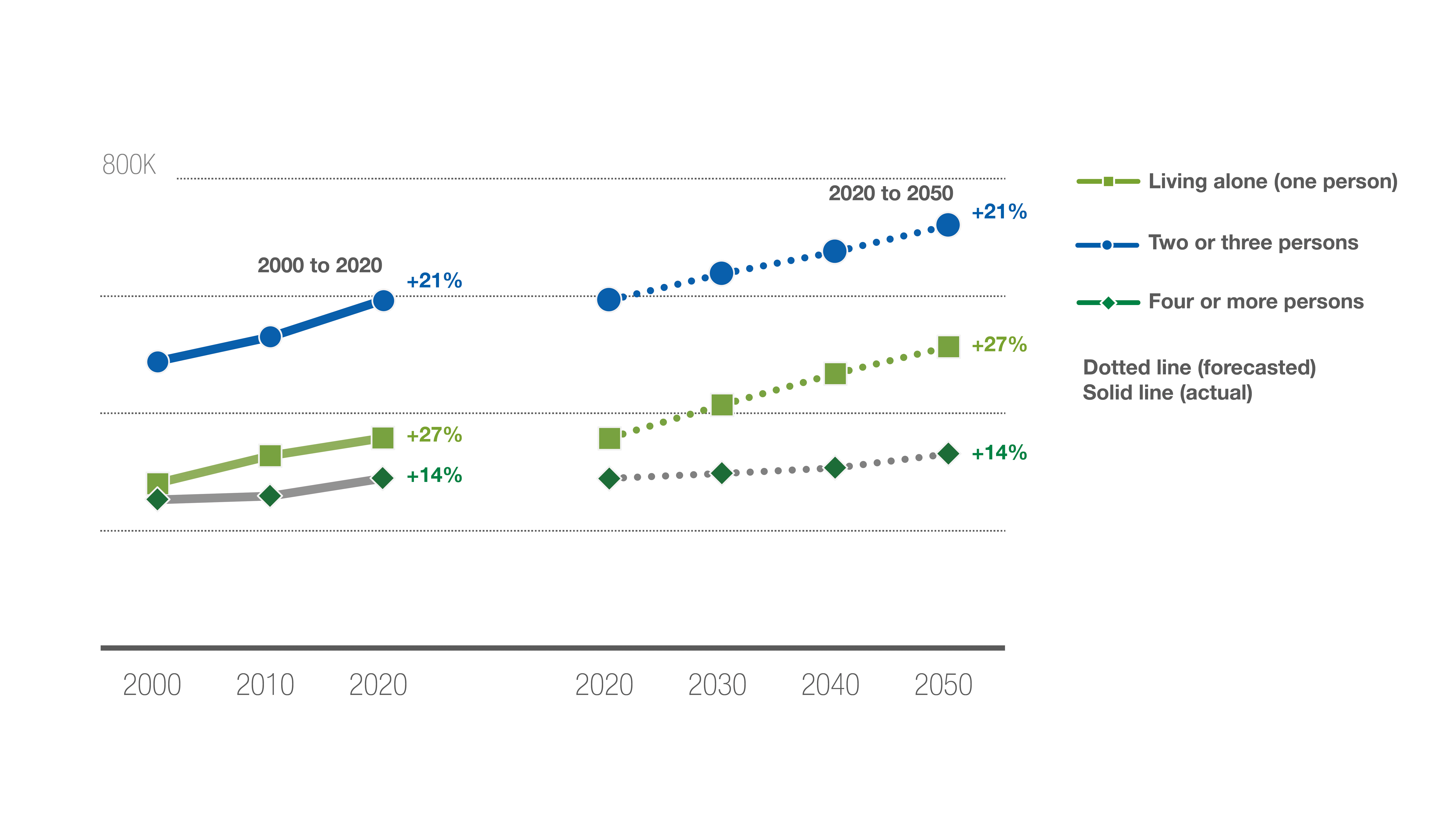

These demographic changes also affect household formation and the number of people living in each household. The region is forecasted to add an additional 324,000 households by 2050, an increase of 26% from 2020. As shown in Figure 9, the number of households categorized as “living alone” will grow significantly over the next 30 years and is almost half (48%) of all new households over the forecast period. Larger household sizes (of four persons or more) will remain a consistent share of the region’s households at about 21%. These changes in household size require us to consider the variety of housing choices the region plans for (See the Housing Policy Plan chapter for further details on planning for housing needs).

Figure 1.9: Forecasted household growth to 2050 by size

Source: Metropolitan Council regional forecast (April 2023).

These two transformational changes – 1) rapid growth of the region’s populations of color and 2) rapid aging of the region’s white population – have significant implications for our future workforce and housing markets.

Our region’s economy

With nearly 92,000 businesses providing over 1.7 million jobs, the Twin Cities metro is the economic hub for the state, western Wisconsin, the Dakotas, and Montana.76 Our region has a strong economic foundation due in part to a mix of nation-leading sectors like healthcare, finance, technology, manufacturing, and education, including several Fortune 500 companies. (See ‘Our region is dynamic and resilient’ for a full description of economic strengths.) Our region’s comparative affordability to other major metros, paired with gainful employment, has meant households could achieve stability if not real economic progress. However, as described earlier, broader economic conditions and trends in job and housing markets may be eroding those pathways, here as elsewhere.

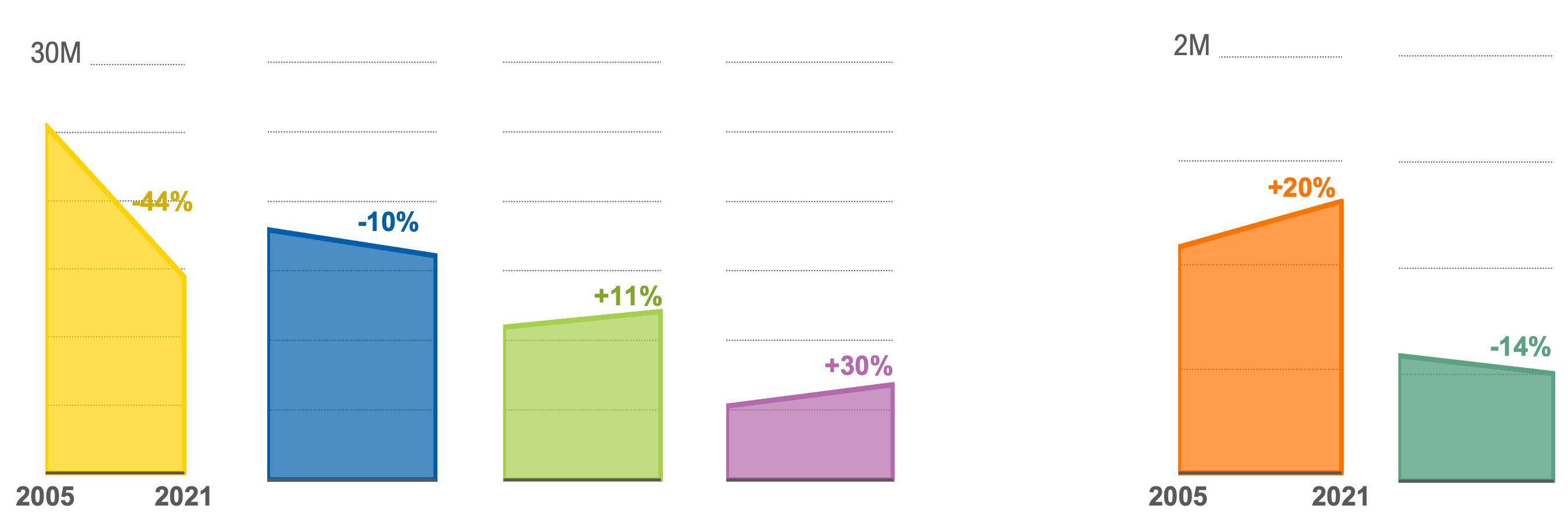

Pandemic disruptions highlight persistent challenges

The region’s economy was experiencing robust economic expansion between 2010 and 2020 until the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted this momentum. As described earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented shock to the region’s economy. Recovery in the region has been slow compared to the nation and peer regions, with employment returning to our two-million-job peak from 2020 only at the start of 2024. Recovery was uneven across sectors, as some industries took an upward trajectory while others lost ground. Employment and production expanded beyond pre-2020 levels in construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, and most of the transportation sector. In contrast, service sectors such as retail, entertainment, and food services, that struggle with lost customer connections, reduced activity, and unused capacity have not yet regained their past employment levels.

Workers of color and immigrant workers were more likely be employed in customer-facing jobs in the service, retail, entertainment, and healthcare sectors when COVID-19 hit, and those sectors shed the highest numbers of jobs during the shutdowns, resulting in higher unemployment rates among those workers.77 But some portion of those jobs (and others in trade and manufacturing, for example) were deemed “essential” and workers of color and immigrant workers stayed employed, typically for low wages, few benefits, and in settings that heightened exposure to COVID-19.78 Serious or prolonged illness could prove to be as financially devastating to economically vulnerable households as job loss outright.79 Though federal relief packages and expanded unemployment insurance benefits helped to offset some of the initial economic shock waves – temporarily reducing disparities in lost income by race and ethnicity – immigrant and refugee workers, especially the undocumented, were not eligible.80,81

The pandemic’s economic impact on people with disabilities was – and is likely to remain – complex.

Labor force participation for people with disabilities in our state and region is already much lower compared to people without disabilities, regardless of race and ethnicity.82,83 Some of this disparity results from disabilities preventing people from working altogether. However, many people with disabilities seek employment but experience barriers like hiring bias among employers, unmet accommodations, and limited transportation options.84 Further, people with disabilities were advised by the public health community to limit their exposure to COVID-19 as much as possible, as some underlying health conditions could lead to more severe cases or other health complications.85

Given that baseline, even fewer people with disabilities in the labor force might have been expected. Instead, recent data show an increase of about 45,000 people with disabilities in Minnesota and an increase of persons with disabilities in the labor force of roughly 30,000 between 2019 and 2021; the overall labor force participation rate is up.86 Much of this increase is attributed to employers’ rapid widespread adoption of remote work, an accommodation disability advocates have championed for many years.87 Not all of it is, however.

This trend is also due in part to the legacy of COVID-19 itself; this virus caused illness and death – and for an estimated 7-10% of adults who contracted it – disability in the form of Long COVID.88 Long COVID includes a variety of physical and cognitive symptoms following a COVID infection that last for at least four weeks; if symptoms limit at least on major daily activity, it is covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).89 University of Minnesota researchers modeled long COVID symptoms as they related to data about disabilities in the U.S. Census’s American Community Survey data and estimated a 16% increase in cognitive disabilities between 2020 and 2021.90 What this means for the region’s labor force longer-term remains to be seen.

During the height of the pandemic (2020-2021), the region’s labor force participation rates fell – like they did nationally – for several reasons, such as accommodating at-home schooling, childcare and other caregiving responsibilities, health concerns about COVID-19, and reduced hours. As jobs returned, workers didn’t, at least not at the pace needed to fill job vacancies, despite considerable (but uneven) wage growth across sectors.91 Low levels of immigration and an acceleration in retirements also played a role in tightening the labor market.92 In 2023, the region had 50,000 fewer workers in the workforce than would have been expected with normal demographic growth. As a result, we continue to have one of the highest rates of job vacancies in the nation, alongside exceptionally low unemployment rates. Misalignment between jobs and workers matters to the region’s economic growth in the short- and long-term.

Future employment growth depends on inclusion

The Twin Cities region is undergoing transformative demographic shifts as described above – an increase in racial diversity and an aging population – that will impact its economic landscape, particularly as it alters the composition of the region’s workforce.

The Baby Boom Generation (born between 1946 and 1965) is now retiring from the workforce. Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and the older members of Gen Z generation (born in the late 1990s) are as numerous as baby boomers but will not achieve a 1:1 replacement in the workforce. If the region’s labor force is to grow, it must come from inclusive strategies; the region’s population growth alone will not suffice. Integrating communities currently marginalized from the region’s economy, including immigrants and refugees, people with disabilities, Black people, American Indian people, people of color, and people over age 65 will play a key role. Continuing flexible work arrangements and remote work and expanding the potential pool of regional workers geographically can also contribute.

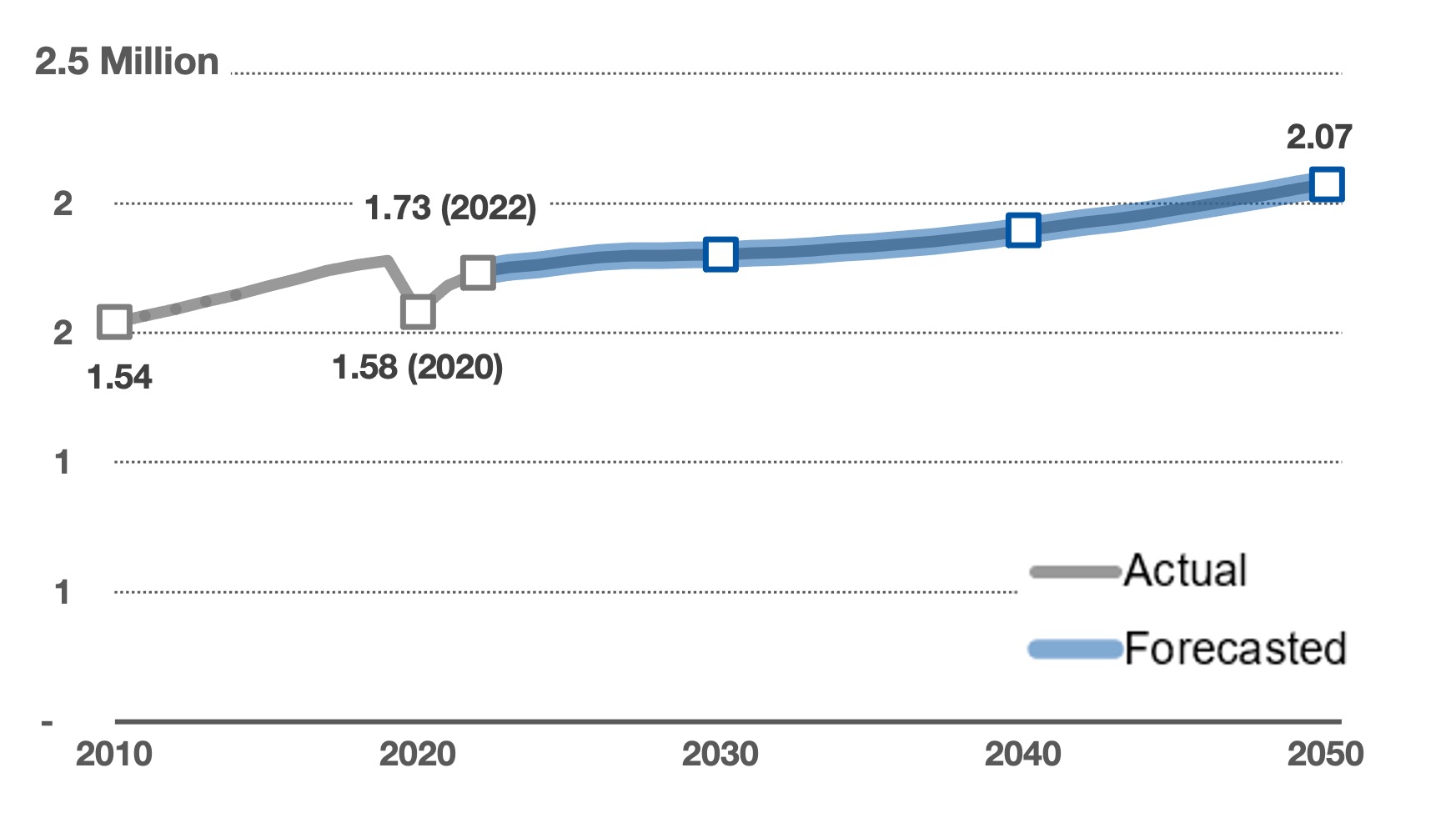

The regional forecast for employment to 2050 reflects these realities. A modest economic expansion is expected over the next 30 years, going from 1.58 million jobs in 2020 to 2.07 million jobs in 2050 (Figure 10). A considerable number of forecasted jobs have already been recovered between 2020 and 2022, so the forecasted growth from 2022 to 2050 is +342,000 jobs.

Figure 1.10: Employment in the Twin Cities region forecasted to 2050

Source: Metropolitan Council regional forecast (April 2023).

The region’s Suburban Edge communities will gain the most jobs between 2020 and 2050 (154,000), followed by Urban (123,000) areas. The Suburban (144,000) and Urban Edge (79,000) communities are not far behind (Figure 11). The distribution of forecasted job growth between 2020 and 2050 overall reflects the region’s employment centers, located in the downtowns of Minneapolis and Saint Paul and in suburban areas. Even in an age of remote work and hybrid work, jobs will continue to cluster geographically and in alignment with regional infrastructure like highways and transit hubs.

Figure 1.11: Forecasted employment growth by Imagine 2050 Community Designations

Source: Metropolitan Council local forecasts (January 2025). See Community Designations in Land Use Policy chapter for more description on what those designations are and the places they describe.

Cities in the region with the highest number of jobs in 2020, like Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Bloomington, Eden Prairie, Plymouth, and Minnetonka, show job growth rates between +19% and +38% during the forecast period. Eagan shows the highest rate of +40.6%. Considerable job gains are also noted in Shakopee, Brooklyn Park, and Burnsville over the next 30 years.

Regional Vision, Values, and Goals

To continue to build on the strengths of our region, and in light of the opportunities and challenges that lay before us, Imagine 2050 defines a vision for the growth and development of the Twin Cities region through 2050. The vision, values, and regional goals were developed and informed by several considerations. These include the vision and plans expressed by communities throughout the region in their most recent comprehensive plans; research on important issues for the region including those related to racial disparities, economic strengths and weaknesses, and climate issues; learnings and findings from engagement that the Met Council has conducted since adoption of Thrive MSP 2040, including themes that have emerged from conversations, research, and engagement in other planning efforts.

Vision for Imagine 2050

A prosperous, equitable, and resilient region with abundant opportunities for all to live, work, play, and thrive.

Shared regional values

The shared regional values are shared core beliefs or principles that guide the work of developing and implementing Imagine 2050. The values build on those identified in Thrive MSP 2040 and incorporate learnings through implementation over the last 10 years as well as the common values expressed by local governments and partners across the region in their plans and programs. Further, these values guide the Met Council’s own approaches to and expectations of partnerships and policy and program development to support full implementation of Imagine 2050.

Equity

We value the people and communities of our region. Our region is economically and culturally vibrant. We also recognize, however, the harm and disparities that injustices, including racism, have created.

We are dedicated to creating systems, policies, and programs that repair and heal past harm, foster an equitable future, and eliminate disparities. Communities that have been marginalized in the past will be at the center of this work in leadership roles.

Leadership

We value those in our region who inspire and motivate others for positive change. Our region is known for its civic engagement. We need broad and inclusive leadership to help confront the significant challenges we face around equity, climate change, safety, and other pressing issues.

To maximize the potential of our region and its communities, we turn to leadership that is diverse, collaborative, culturally competent, and innovative. We encourage this kind of leadership across all sectors including business, government, nonprofit, and education.

Accountability

We value being effective in our work and achieving measurable outcomes. Our region is known for its research, initiatives, and collaborations. We must be open to criticism and clearly understand when we are not achieving results or have harmed communities.

We recognize that we can maximize our effectiveness by being in partnership with others. We will also be transparent and flexible so that we can change course when needed.

Stewardship

We value our region’s resources. Our resources include our natural, economic, and financial resources as well as our infrastructure. We recognize that these resources may be vulnerable over time to changing conditions, including from climate change.

We must design our systems and allocate our resources in ways that can be sustained over time and support the needs of future generations.

Regional goals

Imagine 2050 is organized around five shared regional goals. The regional goals identify the desired end states for the major cross-cutting issues facing our region. It will take actions from all levels of government, partnerships with nonprofit organizations, education institutions, and other leaders, and actions across the full spectrum of policy areas to effectively achieve these goals. No one partner nor one program will achieve any of the regional goals on its own.

The five regional goals will be achieved through our policies and actions that inform practices, programs, and partnerships.

- Our region is equitable and inclusive.

- Our communities are healthy and safe.

- Our region is dynamic and resilient.

- We lead on addressing climate change.

- We protect and restore natural systems.

No one goal can be successfully implemented in isolation. Rather, Imagine 2050 recognizes the interconnectedness of the goals and the importance of integrated approaches to realize the intended outcomes. For example, we can only lead on addressing climate change if we are also protecting and restoring natural systems and doing so in an equitable and inclusive manner. It is in the intersection of the regional goals where there is the potential to have the greatest impact on the region. Successfully advancing the regional goals requires attention to each of the goals in all our actions, policies, and programs. Integrated approaches and strong partnerships are key to achieving the regional goals and vision.

More specifics regarding each of these regional goals are detailed in the sections of this plan below. Each of the chapters of Imagine 2050 (housing, land use, transportation, parks, and water) details objectives, policies, and actions that together advance the shared regional goals and the regional vision. Objectives articulate the achievable results that advance each regional goal and are accompanied by policies and actions that can be implemented through specific actions by the Met Council and our partners. While this plan sets a foundation for local comprehensive planning, it also is a statement of the Met Council’s commitments to advance regional goals and provides directional guidance and identifies priorities for our own programs, investments, and activities.

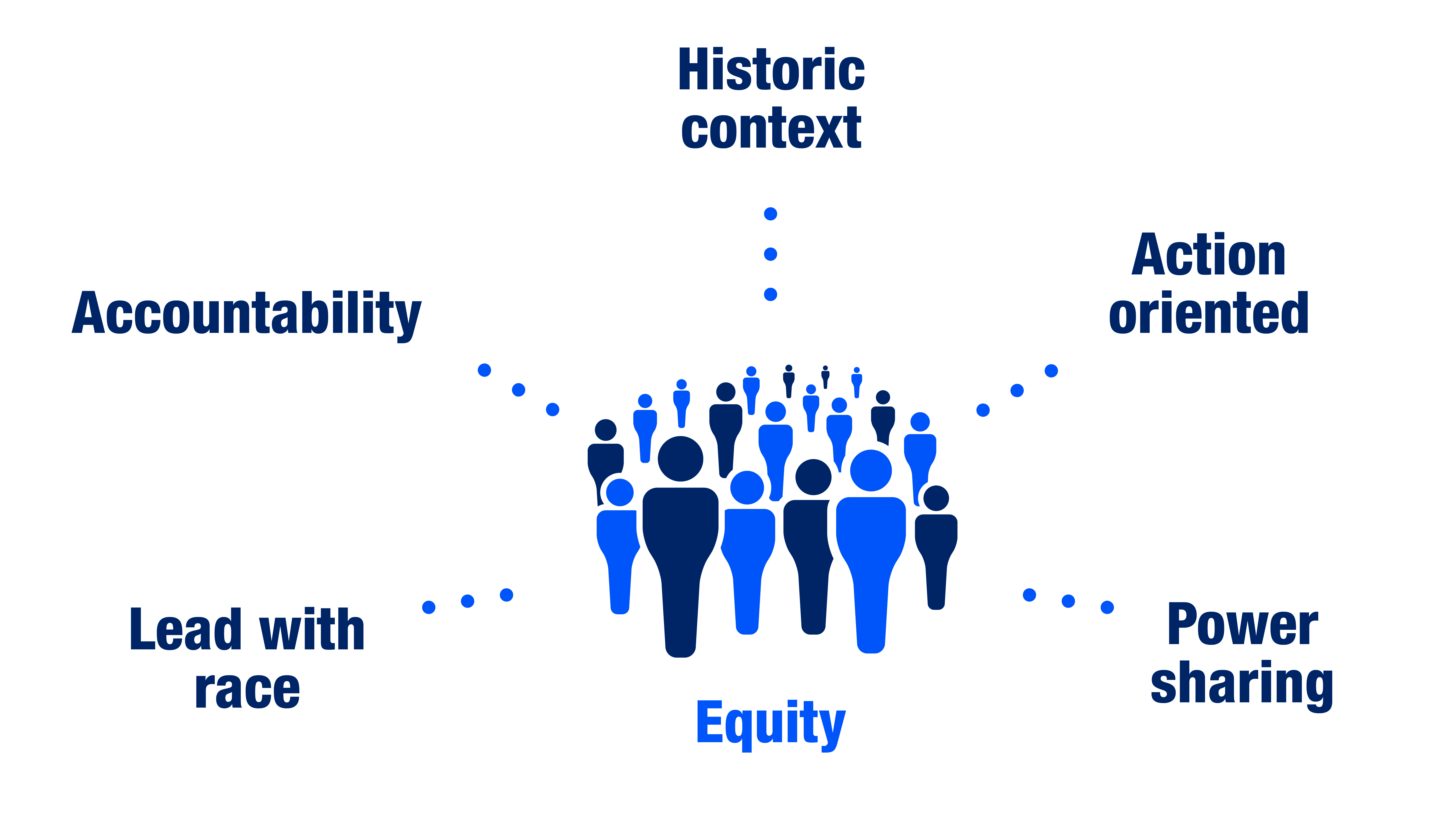

To achieve the regional goal of an equitable and inclusive region, the Met Council has developed a series of frameworks to guide the regional and local planning processes, the work of the Met Council, decision-making across the region, and implementation of priorities established in Imagine 2050. Each framework addresses a key issue which in itself can affect change, and taken together can significantly alter the lives of the most vulnerable populations in this region.

The Met Council will use these frameworks in projects, policy, processes, and procedures to convey a singular message to Met Council partners in how this organization leads and conducts our business. We will share incentives, tools, technical assistance, resources, and lessons learned with partners and local governments to influence and support change at the local level. We will also regularly evaluate and report on the implementation of the equity frameworks and the related commitments, objectives, and actions in Imagine 2050.

Our transition to a framework model to advance regional equity builds on insights gained after Met Council named equity as a regional outcome in the previous regional development guide. Though Thrive MSP 2040 established the Met Council’s commitment to advancing equity, it structured the discussion around containing an expansion of concentrated poverty in the region. This proved to be a limited and limiting approach that further harmed marginalized neighborhoods.93 As such, the Met Council has continued to work with partners in the region to evolve both our approaches to advancing equity across the region as well as to how we structure our analyses and evaluations. The frameworks in Imagine 2050 reflect these changes.

Patterns of historical injustices

As history and continual engagement and community collaboration insights have demonstrated, it is imperative that the Met Council works toward creating an equitable region. The lasting impacts of historical injustices, systemic racism, and discrimination continue to reverberate within our region, disproportionately impacting Black people, American Indians, and people of color. Discriminatory and racist policies were thoroughly planned to benefit white Americans, perpetuating a cycle of exclusion for Black people, American Indians, and people of color. And seemingly race-neutral policies continue today, with inequitable impacts and outcomes persisting in the region and across a variety of outcomes. It is important to recognize these historical impacts and to understand the context that led to our present-day disparities in order to be successful in eliminating the disparities.

The United States itself is built upon legacies of land theft, colonization, and slavery. The original stewards and kin of the land are the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. The seven-county region exists on the homeland of the Dakota peoples and near treaty lands of the Ojibwe and Ho-chunk peoples. Dakota, Ojibwe, and Ho-chunk peoples have survived centuries of genocidal policies, broken treaties, and discrimination in this region. Currently, American Indian peoples from hundreds of tribes have relocated to the Twin Cities, and 42% of American Indians in Minnesota live in the metro area.94

Slavery and its legacy

Slavery, defined as a person who is treated as the property of another person, was practiced in the United States until the passing of the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865.95 While slavery was not legal in Minnesota, enslaved people were forcibly brought to Minnesota in the 1800s with many living at or passing through Fort Snelling. Southern slaveowners were also frequent tourists to the region during the mid-1800s and invested in business and institutions, influencing the early economy in the state.96

The lasting effects of slavery are foundational to systemic racism97 and anti-Blackness.98 Historical slavery practices have continued in the inequities found in modern-day policing99 and have persisted in modern incarceration rates and criminalization of the Black population.100 In 2019, the incarceration rate for Black people in the Twin Cities was 11 times the rate for white people.101 When interacting with police between 2016 and 2021, Black people made up 27% of policing deaths by use of force in the region despite making up 7% of the population at the time, and American Indian people made up 6% deaths despite making up 1% of the population at the time.102

The legacy of slavery has also fueled discriminatory policies103 and continues to affect the health and the economic, social, and cultural well-being of Black communities and people of color today. For example, as we work to create public spaces for community connection, access to those spaces can be limited by the interpretation and enforcement of loitering and lurking laws. A Black person is 27 times more likely to be arrested for loitering in the region.104 Other policies such as some “crime-free” housing ordinances, claiming to reduce illegal activity, have been found to violate the Fair Housing Act because they led to Black and Latine renters getting evicted at higher rates than white renters105,106 and to discriminate against those with disabilities.107 Discriminatory practices and policies that result in incarceration and eviction create additional barriers to accessing rental housing and employment because of one’s record of involvement with the criminal justice system. As the region plans for a more just future, we must be mindful of how systemic issues permeate into seemingly race-neutral programs and policies. As a region, we all have a responsibility to remove barriers to equitable outcomes so people can have healthy social connections, and safe and dignified communities in which to live.

Racial covenants and redlining

Starting in the early 20th century, the Great Migration brought an influx of Black residents to cities in the Northern, Midwestern, and Western United States who sought to escape discrimination and racial violence in the South.108 White residents across predominantly white cities used racial intimidation, violence, and legal action against their Black and people of color neighbors. In response to these demographic changes, the real estate industry and city planners in many parts of the U.S. responded by including exclusionary and racist “racial covenants” in the deeds of homes, furthering segregation efforts. These racial covenants explicitly prohibited many racial groups – particularly Black residents - ethnicities, and nationalities from being able to choose where they wanted to live. By midcentury, over 25,000 properties in Hennepin and Ramsey counties included racial covenants,109 effectively segregating neighborhoods.

Racial covenants influenced the subsequent practice of redlining. Redlining refers to a neighborhood classification scheme developed by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). HOLC categorized neighborhoods based on perceived financial risk and consistently classified neighborhoods that were predominantly communities of color as ‘hazardous’ for loan guarantees. Redlining occurred regardless of how affluent a community was – even wealthier neighborhoods were redlined if they were predominantly communities of color, and particularly if they were Black communities. Redlining depressed property values, and this now-cheaper land was desirable for industries. Some redlined areas had previously existed near heavily polluting land uses, but with the advent of these distinct low-land-value areas, more industrial land uses moved in.110

Although the use of racial covenants on houses was made illegal in Minnesota in 1953 and the Fair Housing Act banned discrimination in housing in 1968, the legacies of these policies are apparent in many disparities that still exist in the region. Redlining has made it difficult for Black, American Indian, and households of color, especially Black households, to build generational wealth.111 Formerly redlined areas exhibit more disparities in education and residents often have less access to green space, environmental amenities, and nutritious, affordable food.

Removal of homes due to highway expansion

The systemic exclusion of Black and households of color from wealth-building opportunities and the violent removal of their communities continued with the 1956 Interstate and Defense Highways Act, which funded highway construction across the country, displacing many residents and destroying neighborhoods. In the Twin Cities, Interstates 94 and 35W were constructed. Rondo, a vibrant Black working class Saint Paul neighborhood, was split in half despite their efforts to protest and lobby against the I-94 highway development.112 The planning and construction of 35W forced out a thriving South Minneapolis Black community113 including homes, prominent businesses, and cultural organizations. Many residents were unaware of the highway development until bulldozers arrived, and compensation for displaced homeowners was inadequate. Renters and businesses, particularly Black renters affected by redlining and racial covenants, received no financial support and were prevented from moving to surrounding neighborhoods, exacerbating their displacement and hindering community connections.

Civil Rights movement

In the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968) began as a social movement effort to defeat legalized racial discrimination, segregation, and disenfranchisement of Black Americans and move towards racial justice. The Civil Rights Movement was shaped by activism, marches, protests, boycotts, freedom rides, and lobbying for legislative action. In the Twin Cities, key civil rights leaders included Frederick L. McGhee, Reverend Denzil A. Carty, Nelle Stone Johnson, and Harry Davis.114 Despite court challenges, police brutality, and racial violence, the Civil Rights Movement prevailed and led to landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education to desegregate schools, Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed all discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. As a follow-up to the Civil Rights Act, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968 to address racial discrimination in housing following the assassination of Civil Rights leader, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.115

Latine people and communities in the region

In the early 1900s, over 7,000 Mexican laborers moved to Minnesota employed by beet farmers, sugar companies, meat-packing plants, and railroad lines. They faced exploitation in the forms of low wages, inadequate housing, unsteady employment, and racism. The Anáhuac Society was formed in 1922 as a community hub to provide local services such as neighborhood guidance, employment opportunities, cultural enrichment, and in some cases, sickness and funeral benefits.116

In the 1960s and 1970s, a growing Chicano Movement occurred as Mexican and Mexican American laborers moved to Saint Paul’s West Side. Chicano activists in rural Minnesota also faced discrimination and barriers as farm workers. They organized Centro Campesino in Southeast Minnesota by 1997. Despite systemic barriers to opportunities such as housing and living wage jobs, the Chicano Movement set a foundation for empowerment for Latine communities in the seven-county region today.117 As Latine people migrated to the region, they began forming community organizations such as Communidades Latinas Unidas En Servicio (CLUES) in 1981, which is now the largest Latino-led nonprofit in the state.

Due to increasingly growing population of Latin American immigrants, more Latin-American-owned businesses were established in Minneapolis in the 1990s. As businesses began to expand and communities blossomed, community leaders wanted to build economic power and self-sufficiency. In 1992 community organizers from Sagrado Corazon church created the Joint Committee on Immigration and the Economic Development Committee to “focus building economic power and promote economic opportunities” in flourishing Minnesotan Latine communities. These eventually became what is officially known as the Latino Economic Development Center (LEDC). The Latine communities in the region are a testament to community power and solidarity.

Asian and Asian American people and communities in the region

The region is home to many diverse Asian and Asian American communities. Asian people comprise 7.8% of the region’s population.118 Asian and Asian American communities in Minnesota encompass people from a diversity of cultures. The region’s largest Asian cultural communities include Asian Indian, Burmese/Myanma, Cambodian, Chinese, Filipino, Hmong, Japanese, Korean, Lao (non-Hmong), Thai, and Vietnamese communities.119

The Twin Cities region has the largest urban Hmong population in the country. Hmong people are the largest Asian group in Minnesota, and Hmong is one of the most spoken non-English languages in Minnesota.120 Hmong people are prominent leaders in the region. After a surge of anti-Asian harassment and violence in the region,121 Hmong Minnesotan leaders led the update of an anti-hate crime bill to include more accessible and culturally responsive reporting measures.122 Hmong businesses and community centers, including the Hmong Cultural Center and Museum,123 are a vibrant and integral part of the region’s cultural landscape.

Anti-immigration and xenophobia

While the United States is comprised of diverse peoples and cultures, we have a longstanding history of anti-immigration policies and xenophobic sentiment. The first explicitly anti-immigration policy was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, setting precedent for additional exclusionary practices discriminating against people of color immigrating to the United States.124 Immigrants had little to no choice of where they could live, resulting in exploitation in housing, labor, environmental hazard exposure, and access to amenities and care. This legacy in discrimination has cultivated xenophobic sentiment in United States culture, including in the seven-county region.125

At times in United States history, government agencies decided to expand policies supporting immigrants. These include the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in 1990, and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in 2012. Such policies provide opportunities for expanded immigration or extension of authorized status for those already in the United States.

Undocumented immigrants are heavily targeted by not only xenophobic and racist policies, but cultural sentiments and political campaigns as well.126 Undocumented immigrants and refugees continue to be placed in poor quality housing and unsafe labor conditions and have limited access to living-wage jobs.127

The largest immigrant populations in the state are from Mexico, Somalia, India, Laos, and Vietnam.128 Minnesota is home to the largest population of Somali immigrants in the country.129 Somali communities and businesses are a prominent part of the region’s development and community building..130 Many immigrant populations and others also face religious-based discrimination, stereotypes, and threats of violence in our region adding to the xenophobic sentiments these communities face.

The region is also a new-found home for refugees, including Somali, Myanma/Burmese, Laotian and Hmong, Ethiopian, Liberian, Afghan, Bhutanese, Iraqi, and Ukrainian refugees.131 The region contains sanctuary cities, including Minneapolis and Saint Paul.132 A sanctuary city is “a municipality that has adopted a policy of protecting undocumented immigrants by not prosecuting them solely for violating federal immigration laws.”

Community engagement recommendations from immigrant communities included expanded use of Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) for obtaining loans and renting homes. Immigrants, including undocumented immigrants and refugees, are an important part of the economy, communities, and cultural landscape that make up our region, and must be respected as such in our region’s policies, practices, and processes.133

Racial intimidation and other discriminatory practices

Despite the legal end of racial discrimination and segregation, racial intimidation and violence against Black, American Indian, and people of color still exists in U.S. culture, including the seven-county region. In addition to anti-immigration and xenophobic sentiments, racial intimidation affects Black communities, American Indians, and people of color through cultural sentiments as well as formal and informal policies and practices.

In relation to racial disparities in homeownership, evidence shows that discriminatory practices including real estate agents steering Black people and other racial minorities to or from certain neighborhoods still exists. After reporting in national newspapers around apparent discrimination in home appraisals, Freddie Mac followed up with a comprehensive study of evaluation of home appraisal gaps between Black and Latino tracts and white tracts and found that homes in Black and Latino census tracts were more likely to be appraised at lower values than comparable homes in white census tracts.134 These systemic practices continue to depress the ability for Black and Latino homeowners to build wealth through homeownership.

Erasure of history in data/narratives

The data and tools we develop must remain people-centered, driven by concerns articulated by overburdened communities, and be deeply interwoven with Met Council processes for budgeting, policy development/prioritization, and program implementation. Too often, purely quantitative approaches to policy inherit biases from the data itself – that is, the research priorities of institutions shape how data is collected and distributed, which inevitably influences the downstream analyses that arise from these datasets.135 This can lead to disconnects in what residents and communities are experiencing and what government entities such as the Met Council acknowledge or commit to address. To combat this bias, we can employ a mixed methods approach that synergizes quantitative analyses with qualitative datasets such as social knowledge and lived experience.

Equity framework