Pedestrian Investment Plan

Table of Contents

Introduction

Walking is celebrated when we take our first steps in life, but after that significant achievement, it is often taken for granted. Yet walking remains our most universal mode of travel – we all walk or roll (using a mobility device such as a wheelchair or walker) and walking also makes essential connections to other modes of travel. When looking at Travel Behavior Inventory data on all trips made in the region using all modes, more are done through walking and rolling (9.0%) than biking (1.2%) or transit (2.8%).

Met Council’s role in planning for pedestrians

While local agencies are primarily responsible for planning and implementing pedestrian infrastructure, the Met Council’s role in planning for pedestrians includes:

- Assessing the trends and needs in pedestrian travel and providing resources to agencies implementing transportation projects to include safe, accessible, and convenient support for pedestrians.

- Investing in walking through the Regional Solicitation, regional transportation sales and use tax, and other unique regional and federal funding sources.

- Providing guidance to agencies working to address regional pedestrian barriers, implementing ADA transition plans and assisting with monitoring progress, and making pedestrian connections to regional destinations.

- Providing guidance for facilities that support transit investments, Livable Communities Act investments, and universal design and equity.

- Providing guidance for local comprehensive plans to ensure walking is a key consideration in land use and transportation planning, including review for planning for continuity and connectivity between jurisdictions.

- Setting overarching land use policy in the region that supports walking and safety for people traveling this way. (Land use is discussed in more detail in the land use portion of Imagine 2050.)

- Ensuring safe, accessible, and convenient pedestrian connections to transit service in connection with our role as a transit operator.

- Certifying that the metropolitan transportation planning process complies with the ADA.

Relationship to plan goals

Planning for walking and rolling supports the five main goals in the Transportation Policy Plan and their related objectives. Each goal is covered in more detail in distinct chapters.

Goal: Our region is equitable and inclusive

Providing safer, more walkable communities supports an equitable and inclusive region. Walking and rolling are universal, regardless of other ways we may travel. For some residents, walking and rolling are more crucial, such as for those who cannot drive due to age or physical condition. Being able to walk to destinations is the most affordable way to travel.

The region has racially inequitable outcomes with traffic safety. For example, Black and American Indian residents have higher rates of pedestrian fatalities in the region, and areas with higher shares of Black or American Indian residents have more pedestrian crashes. These findings may be linked to exposure, but they closely mirror historic patterns of disinvestment and racially biased lending practices. Beyond traffic safety, we know residents experience our transportation system in different ways based on intersections of their identities, such as race and ethnicity, disability, or gender.

Goal: Our communities are healthy and safe

Safe ways to walk and roll benefit our physical and mental health and help connect us to community. Under this goal, people walking or rolling do not die or face life-changing injuries. They feel safe, comfortable, and welcome. With safer, more comfortable facilities, people have more opportunities to walk or roll. Safe ways to walk and roll must address crossing roadways, not just walking along them on sidewalks.

Goal: Our region is dynamic and resilient

Planning for safe, direct, and reliable walking and rolling supports this regional goal by providing another option for travel. Part of planning for walking and rolling will need to ensure that the infrastructure for doing so can withstand and recover quickly from natural and human-created disruptions, whether from increased snowfall events, increases in freeze-and-thaw events, or localized flooding that can have bigger impacts on people who are walking and rolling.

Goal: We lead on addressing climate change

Walking and rolling produce zero emissions and can contribute to the region minimizing our contributions to climate change. In addition, the majority of the region’s residents who use transit access it by walking or rolling. Safe, comfortable infrastructure for pedestrians supports more zero emission trips made by walking, strengthens the ability of our transit system to better serve travel needs, and helps reduce vehicle miles traveled.

Goal: We protect and restore natural systems

Infrastructure for walking and rolling can minimize impacts on natural systems through its generally smaller footprint than infrastructure for vehicles. People walking and rolling will benefit from protection and restoration of natural systems, such as tree canopy, that provides shade.

Existing Conditions

This section broadly describes the existing facilities and features of the pedestrian system. There are also discussions about pedestrian system challenges around the needs of people with disabilities, winter maintenance, and safety.

Pedestrian facilities and features

Walking is an essential means of travel within the regional transportation system, but availability, type, and quality of facilities for walking vary across the region. Facilities for walking include a few state trails in the metro, regional trails (as designated in the Met Council’s Regional Parks Policy Plan), local multiuse paths, sidewalks, skyways, and pedestrian or multiuse bridges or underpasses.

Examples of pedestrian facilities

Pedestrian facilities are more than just sidewalks and multiuse paths. Often the most dangerous part of walking or rolling is crossing streets, so street-crossing treatments are just as critical for safe travel by people walking and rolling. These treatments can include elements such as:

- Crosswalks (marked and unmarked) of different types for increased visibility

- Raised crossings to prioritize pedestrians at conflict points

- Advance stop bars, which are solid white lines striped ahead of crosswalks to show drivers where to stop

- Curb extensions to reduce crossing distances and exposure and improve pedestrian visibility

- Street designs that slow driver speeds

- Medians designed with pedestrian refuge islands

- Pedestrian-scale lighting to increase safety and visibility to drivers

- Leading pedestrian intervals used at traffic signals to give a head start to pedestrians in crossing the street

- Rectangular rapid flashing beacons, or pedestrian hybrid beacons at midblock crossings or intersections without traffic signals

- Separation from roadway curbs through buffers such as boulevards to help minimize stress from vehicle traffic

Many of these treatments are identified in the Federal Highway Administration’s Proven Safety Countermeasures and can be used in different community types, from urban to suburban and rural. They have also published a reference on Proven Safety Countermeasures in Rural Communities that focuses on those most applicable in this context. For additional reference on pedestrian facility design, MnDOT provides Minnesota’s Best Practices for Pedestrian/Bicycle Safety. MnDOT’s Facility Design Guide includes a chapter on nonmotorized facilities. The Work Program for this plan also includes a project to develop a Complete Streets Local Implementation Guide that will provide additional guidance on implementing streets that are context sensitive for all users.

Paved shoulders may be used by pedestrians where not specifically prohibited, though separated facilities reflect more of a Safe System Approach and Complete Streets implementation.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), facilities must also be accessible to people with different types of disabilities. While this is not a complete list, these accessibility requirements include:

- Curb ramps with detectible warning surfaces

- Accessible pedestrian signals for people with visual disabilities

- Passing spaces where continuous width does not provide for passing

- Cross slope and running slope maximums

Other supportive elements

Other features may not be explicitly considered pedestrian facilities but can be important supports for pedestrians of all abilities to travel with safety, dignity, and comfort. Examples include:

- Shade (whether from tree canopy or structures)

- Lighting that works at a pedestrian scale

- Places to sit and to rest

- Public water fountains

- Public restrooms

Traffic calming and changes to roadway configurations can have significant safety and comfort benefits for people walking or rolling as well as drivers. Roadway reconfigurations are included in the Federal Highway Administration’s Proven Safety Countermeasures. These reconfigurations are usually when an existing four-lane undivided road is changed to a three-lane road that has two through-lanes and a center left-turn lane.

Ongoing pedestrian challenges

While the official pedestrian facilities described above can take many different forms, people can walk or roll many places throughout the region, regardless of whether the facilities are officially designated for pedestrians. Where no pedestrian facilities are provided, people are often forced to walk or roll on the edges of roads, sharing space with vehicles traveling at speeds that could likely kill them. People who walk or roll need an accessible and safe network to use, no matter their age or abilities.

The urban core of the region has the most connected pedestrian network, but it becomes sparser through the rest of the region due to previous development patterns and underinvestment. Pedestrian facilities are usually needed on both sides of a roadway to serve destinations on each side, but there may only be facilities on one side coupled with a challenging environment for crossing. People walking and rolling are more sensitive to weather conditions and distance and tend to take the most direct route. In areas without sidewalks, paths can often be seen worn into the dirt where people are walking in grass to get where they need to go.

For people to walk or roll to their destinations, connections often cross both public and private property, and the entire trip needs to be considered when planning for good experiences for people walking or rolling. Private development that includes parking lots can also be challenging for people to navigate safely and comfortably when walking or rolling. To create the best environment for pedestrians, land use and development are also important considerations along with transportation. Land use is discussed more in the Land Use Policy Plan.

Better meeting needs of people who have disabilities

Pedestrian facilities are particularly important to people who have disabilities. For people with disabilities, it is considerably more difficult to nearly impossible to travel where there are no pedestrian facilities. People who use wheelchairs or walkers may especially need to use the street when sidewalks and curb cuts are incomplete, uneven or obstructed, especially in winter when snow and ice may not be promptly cleared. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is federal civil rights law that requires all government entities that provide transportation services and/or infrastructure to ensure that people with disabilities can use the transportation system in an accessible, equitable, and safe manner.

For the pedestrian network, the ADA requires different elements to make the system more accessible for different disabilities. These requirements are considered to be the bare minimum for access. Curb ramps allow people who use wheelchairs or walkers to safely travel along sidewalks and cross. Detectable warnings on curb ramps allow people who are blind or have low vision to know that they are entering an area with potential conflicts with vehicle traffic. Accessible pedestrian signals provide vibrotactile buttons (providing vibration people can sense) and audible alerts to let people who are blind or have low vision and those who are also deaf know when walk signals are on to cross streets. Slope requirements address the need for stable surfaces for people with different impairments, especially people using manual wheelchairs. More information about all of the requirements for the public rights of way is available from the U.S. Access Board.

In the Twin Cities region, 1 in every 11 residents has a disability. As people age, disabilities become more common, so the region will likely have significantly more people with disabilities as the share of residents who are 65 or older increases. By 2050, the region expects to have 22% percent of residents who are 65 or older, compared to 15% in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic also increased the numbers of people in the United States reporting they have disabilities. Disabilities are also more common among some people of color. About one in every six residents who are American Indian has a disability, and about one in every eight Black residents has a disability. Ensuring the region is accessible for people with disabilities is an equity issue. The core of the challenge is changing an environment that is built and operated in ways that do not meet the different accessibility needs of people.

Federal Highway Administration emphasis on ADA transition plans

The U.S. Department of Transportation has put greater emphasis on ensuring compliance with the ADA. In 2015, USDOT guidance to metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) on planning emphasis areas included a focus on providing access to essential services. This includes evaluating compliance with the ADA to help people with disabilities gain needed access to services and destinations. Beginning in 2016, the Minnesota division of the Federal Highway Administration asked metropolitan planning organizations in Minnesota to do ADA-focused work, including coordination and monitoring of progress, as part of the MPO requirement to certify the metropolitan transportation planning process is being done in compliance with the ADA, among other requirements in 23 CFR 450.336. This includes required transition plans in the region. The Met Council certifies this process annually with its submittal of the Transportation Improvement Program.

As part of the certifications for 2019-2022 Transportation Improvement Programs, Minnesota MPOs were asked to survey local agencies about the status of their ADA transition plans and report the responses to the division office. Federal funds could have potentially been withheld if local agencies did not have or were not making substantial progress toward completing the required ADA transition plans. The point of these plans is to remove the identified barriers for people with disabilities to have equitable access to the transportation system and public services.

The ADA requires that all government agencies conduct a self-evaluation of facilities, programs, and services to identify any that must be modified to remove barriers to participation by people with disabilities. In addition, any government agency with 50 or more employees must also have an ADA transition plan. The transition plan details the steps needed for removing barriers and making the community more accessible. These plans must identify physical obstacles that limit accessibility, describe the methods for making the facilities more accessible, specify a schedule for each year of the transition period, and indicate the responsible official for plan implementation. Because sidewalks can potentially be barriers for people with disabilities due to slope, obstructions, width, gaps, or other elements, they are required to be included in self-evaluations and transition plans.

When the Met Council first surveyed local agencies in 2018 (28 years after the ADA became law), 46% of agencies had a transition plan, and 40% were in the process of creating one. In 2018, a qualifying requirement was added to the Regional Solicitation for applicants to have an adopted ADA transition plan or self-evaluation to prompt agencies to meet this longtime need. According to the second survey done by the Met Council in 2021, 88% of agencies reported having a transition plan, and 9% were in the process of doing one. Having a plan is just one step toward transitioning to a transportation system that is fully accessible to everyone. Removing the barriers helps provide access to all.

MnDOT’s approach to ADA and designing with disabilities in mind

The Federal Highway Administration created a map of state Transportation Departments’ ADA transition plans and inventories in 2023 to help these departments and the public better understand the purpose of the plans. The Federal Highway Administration notes that federal funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law can help accelerate implementation of these plans toward more accessible transportation systems.

Figure 11.1: Residents that have a disability

In Minnesota, MnDOT is committing to achieving substantial compliance with the ADA on its system no later than 2037. Progress on accessibility improvements on the state system are tracked not only through MnDOT’s performance dashboard for Minnesota GO but also through the state’s Olmstead Plan, which is designed to help the state “to provide individuals with disabilities opportunities to live, work, and be served in integrated settings.”

Guidelines and resources on ADA planning and implementation

A casebook of success stories on Creating High-Quality ADA Transition Plans for the Pedestrian Environment was released in 2023 by the Great Lakes ADA Center and the University of Illinois -Chicago. It outlines several key elements of successful implementation of ADA transition plans by local agencies. Among these elements are “having a specified target for achieving barrier removal” and “monitoring progress yearly.” MnDOT’s example of reporting annually and having a target date of 2037 for compliance is one the rest of the region should follow to ensure we are better meeting the needs of people with disabilities. The time horizon of this plan (year 2050) comes 60 years after the adoption of the ADA, and local agencies should strive for accessible networks no later than 2050.

In 2023, the Public Right of Way Accessibility Guidelines Final Rule was published by the U.S. Access Board after decades of work. These guidelines became effective on Sept. 7, 2023. After the U.S. Departments of Transportation and Justice adopt the guidelines, they will become enforceable by law. The U.S. Department of Transportation issued its final rule for Public Right of Way Accessibility Guidelines for new construction and alteration of transit stops on December 18, 2024, which is effective beginning January 17, 2025. The Department of Justice has indicated plans for rulemaking on these guidelines beginning in 2025. Agencies can still follow the guidelines now to ensure their public right of way is more accessible to people with disabilities.

MnDOT began implementing portions of the guidelines relating to curb ramps in 2010. Standards adopted by the Departments of Transportation and Justice must be consistent with the public access guidelines and not provide less accessibility than what was included in the U.S. Access Board’s final rule. If agencies are not currently following these guidelines, it would be good stewardship to begin doing so rather than just following existing standards. The guidelines cover many areas relating to pedestrian travel, including pedestrian access routes along sidewalks and shared use paths, alternate pedestrian routes in construction areas, curb ramps, detectable warning surfaces, accessible pedestrian signals, pedestrian medians at crossings, and transit stops and shelters.

Role of universal design in meeting the needs of all ages and abilities

The ADA is just the baseline of the legal minimum required for people with disabilities. Ensuring ADA compliance doesn’t ensure a transportation facility fully meets the needs of all users, including all people with disabilities. For example, the existing guidelines don’t fully address the needs of people with cognitive or sensory disabilities.

To truly meet the needs of all ages and abilities on our transportation system, the region must also think beyond minimum compliance toward universal design. Universal design ensures that our environments, including the public right of way, are designed to work for everyone, regardless of age, ability, or size. Universal design includes seven principles:132

- Equitable use – useful for people with different abilities

- Flexibility in use – useful for a wide range of abilities and preferences

- Simple and intuitive use – easy to understand, regardless of individual language, experience

- Perceptible information – necessary information is effectively communicated

- Tolerance for error – minimizes hazards or adverse consequences

- Low physical effort – use minimizes fatigue

- Size and space for approach and use – allows for differences in body sizes, position whether seated or standing, mobility

Universal design elements can include:

- Wider sidewalks and paths to allow people to travel side by side

- Enclosed spaces for socializing or sensory processing

- Street trees and traffic calming to help minimize stress from vehicle noise

- Clearly defined and marked spaces, which can use color and texture for these distinctions

- Frequent seating, including options with arm rests to use to brace while sitting or standing up

Ongoing engagement with people with different disabilities and needs can help ensure designs address the full range of needs.

One example of what universal design could include for transportation and streets comes from work done by Alexa Vaughn and Gallaudet University on DeafScape and DeafSpace. Gallaudet University’s DeafSpace Design Guidelines help architects and planners design the built environment so that it removes physical barriers for people who are deaf.

Disabilities are created by environments designed without consideration of the wide range of potential needs. DeafSpace identified five areas where the built environment (with more emphasis on buildings) can create better spaces for those who are deaf, as well as others in the community. Alexa Vaughn applied DeafSpace to urban design and landscapes with DeafScape. Elements include wider walkways so that people who use sign language have enough space to communicate with each other, flexible seating in public spaces to adjust for needed lines of sight, and using textured transitions and visual clues to aid with orientation.

An Urban Deafscape

Winter maintenance

Planning studies routinely identify the need for reliable and timely winter maintenance for pedestrian facilities. In addition, the ADA requires agencies to maintain pedestrian facilities in accessible conditions throughout the year with only isolated or temporary interruptions due to maintenance or repairs.133 The region’s Public Transit and Human Services Transportation Coordinated Plan from 2020 identified creating and maintaining accessible pathways and transit stops as one of the high priority needed strategies, with timely snow and ice removal as part of that needed work. The 2023 Transportation Needs in Daily Life study echoed this critical need.

The responsibility to do this critical maintenance is spread across many different partners, and agencies may address these needs in different ways. Some cities consider snow and ice removal for sidewalks to be the responsibility of adjacent property owners with enforcement done by the city, while some cities provide municipal clearance for pedestrian facilities. The Minnesota Department of Health provides case studies on options for this needed maintenance and impacts on public policy.

While the need for better winter maintenance is a common concern for people walking and rolling, there is less understanding of how different policies and practices across the region work effectively to address this need. While technology is often identified and developed for other modes of transportation, it often has not been a priority for helping to support people walking and rolling. A 2023 research project done by MnDOT and the Local Road Research Board on Designing and Implementing Maintainable Pedestrian Safety Countermeasures identified recommendations for year-round maintenance considerations for other pedestrian infrastructure used in safety countermeasures such as crosswalks, curb extensions, medians with pedestrian refuge islands, and speed humps or tables. These recommendations included addressing designs that can be maintained in winter operations.

Safety

While this topic is covered in more detail in the Safety section of the Transportation Overview, this section discusses some highlights of how safety relates to pedestrians including the relationship to Safe System Approach and the findings from the Regional Pedestrian Safety Action Plan.

Safe system and pedestrians

The Safe System Approach is discussed more fully in the Safety section of the Transportation Overview. Crash risks are addressed through the five elements of the Safe System Approach. This approach, promoted by the USDOT, is an important shift in safety planning and implementation. It provides a more holistic approach to addressing safety in systems rather than as individual problems or solutions.

The principles that humans make mistakes and are vulnerable are a key aspect of the Safe System Approach. This approach recognizes that it is unrealistic to expect perfect human behavior to eliminate deaths and serious injuries from traffic crashes. We need redundancy in our system so that when mistakes happen, people don’t pay with their lives or future abilities. This is an especially important concept when planning for pedestrians and their safety. We need to address systemic issues rather than individualize responsibility. This means, for example, ensuring the transportation system is sufficiently lighted and driver speeds are slow enough to support the visibility of people walking and rolling, rather than expecting everyone walking and rolling to make certain clothing choices like wearing brighter colors. While responsibility is shared among governments, industry, other stakeholders, and travelers on our transportation system, not all people have the same impacts on outcomes. Drivers of vehicles and people walking don’t share the same level of impact in the system.

Figure 11.2: Safe System Approach Principles and Elements134

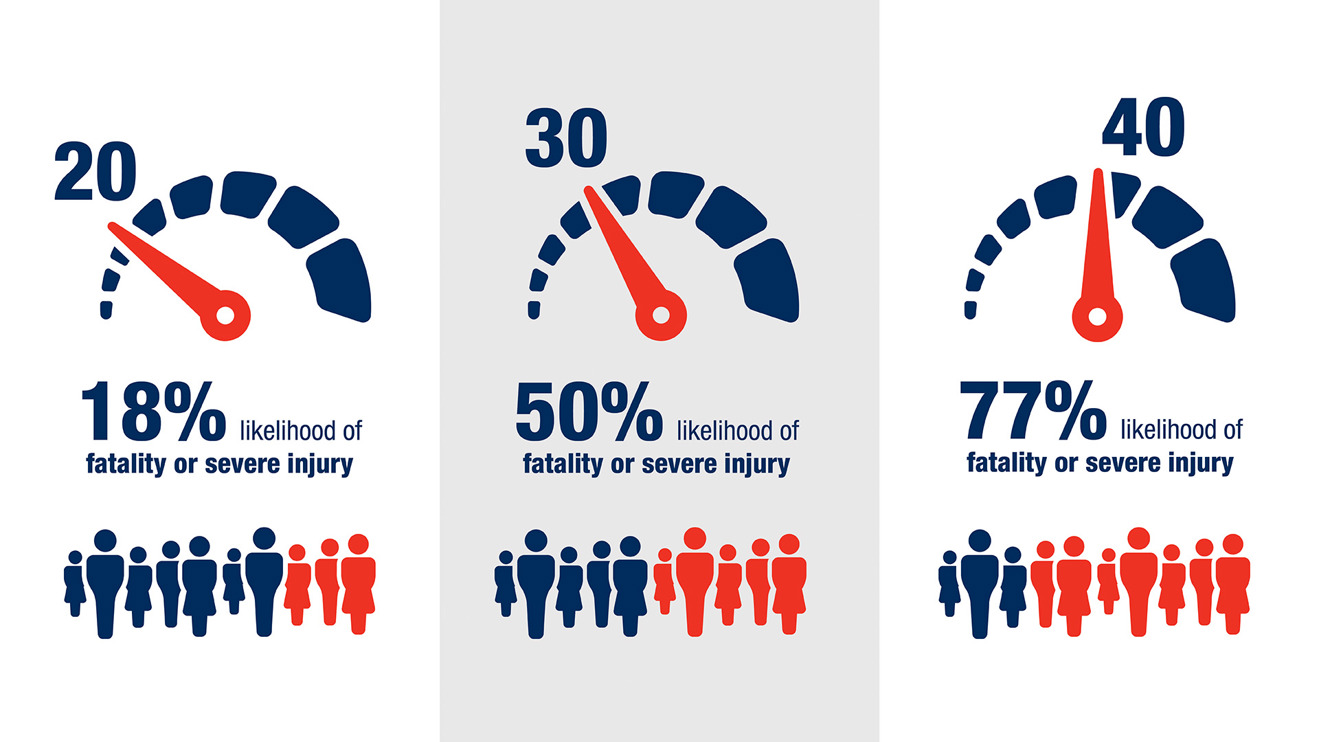

Recognizing the role of speed in a safe system is another important distinction with this approach, especially with pedestrians. Vehicle speed is one of the crucial factors in the likelihood that a pedestrian will die or be seriously injured if they are hit by a driver. The Safe System Approach includes the principle that human bodies have inherent limits on the impacts they can absorb in a crash. The transportation system needs to be designed and operated in a way that focuses on these limits to eliminate deaths and serious injuries. The safer roads and safer speeds elements include designing roads to promote safer speeds, mitigate human mistakes, and facilitate safe travel by the most vulnerable users, including pedestrians. Traffic calming elements for roadways remain an important ongoing strategy to help counter the physics of crashes with drivers of vehicles and pedestrians.

Figure 11.3. Effect of speed, in miles per hour, on pedestrian risk

In the United States, vehicle sizes, weights, and designs have changed in the past decade in ways that are detrimental for pedestrian safety. Increased hood heights and bluntness change how and where a pedestrian is impacted in a crash, potentially leading to more severe outcomes. This issue is also briefly discussed in the safe vehicles section of the healthy and safe section of the Transportation Overview. The policies and actions also include an action to look at local options to address increased vehicle weights and sizes.

Findings from the Regional Pedestrian Safety Action Plan

In 2022, the Met Council completed a Regional Pedestrian Safety Action Plan. The plan analyzed pedestrian crash trends and risk factors for all roads in the region, with an emphasis on fatal and serious injury crashes, and a systemic safety analysis to identify risk factors. Other previous safety planning work for MnDOT and counties focuses solely on the systems each agency maintains; this study was a holistic look at the region. A pedestrian safety measure was added to three of the roadway categories in the Regional Solicitation based on the findings of the analyses done in this project.

Key findings from the historic crash data analysis for 2016-2019 included:

- Pedestrian safety is an issue throughout the region. More crashes occurred in urban areas (2,287 crashes, of which 15.6% were serious injuries or fatal), while a greater percentage are severe in rural areas (68 crashes, of which 47.8% were serious injuries or fatal). The significant percentage (70% for all pedestrian crashes and 57% for severe crashes) in urban areas demand attention, and the higher severity in rural areas also needs action.

- Fewer than 25% of all intersections are within 500 feet of a transit stop, yet nearly 80% of fatal or serious injury intersection crashes were near a transit stop.

- More crashes and the most severe crashes happened at intersections with a signal (1,413 crashes, of which 16% were serious injuries or fatal).

- There was no discernible pattern of youth pedestrian crashes happening near schools that was disproportionate in frequency or severity.

- Black and American Indian people are disproportionately killed while walking. (14% of pedestrians killed were Black, compared to being only 9.6% of the region’s population. 2.3% of pedestrians killed were American Indian, compared to being only 0.48% of the region’s population.)

- Neighborhoods with higher percentages of people of color, people with disabilities, and households with lower incomes experience higher prevalence of pedestrian crashes, including fatalities and serious injuries. These findings may be linked to exposure, but they closely mirror historic patterns of disinvestment and racially biased lending practices.

The systemic risk analysis key findings are illustrated in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4: Pedestrian crash risk findings

Because pedestrian count data is not widely available throughout the region, the project used proxies to understand where people would most likely be walking. The systemic analysis identified locations where there is a higher risk of a pedestrian crash.

The plan also provides countermeasure resources for partners to use to identify the best infrastructure changes to address pedestrian safety in their communities.

The Met Council is developing a follow-up plan that will be finalized by the end of 2024. This Regional Safety Action Plan focuses on vehicle crashes and bicycle-vehicle crashes. However, it will also include identification of high-injury streets in the region for pedestrians, building on analysis that was done in the pedestrian plan.

Analysis done as part of the annual target setting for the safety performance measures shows that pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries have increased since 2020, underscoring the need for pedestrian safety improvements.

MnDOT Vulnerable Road User Safety Assessment

In 2023, MnDOT completed a federally required Vulnerable Road User Safety Assessment for the state. This assessment is required by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to be done by state departments of transportation every five years. When compared to the state, the region has a higher percentage of crashes that involve these road users (which also includes bicyclists). The report notes that of all types of road users, “Pedestrian crashes are the most likely to result in a fatality or serious injury.”135 The vast majority – “approximately three-fourths” – of pedestrian crashes with injuries in the state happen in this region, which has approximately 55% of the state’s population.

Pedestrian Plan and Investment Direction

This section includes considerations for local plans in addressing needs for walking, guidance and factors in regional funding decision-making, and funding programs available for meeting pedestrian infrastructure needs.

Planning for pedestrians

Comprehensive plans should address pedestrian needs

Local comprehensive plans should address the needs of pedestrians for transportation. Often these plans may have a more recreational focus on parks, yet transportation needs of people walking and rolling cover the whole community. The necessary planning for pedestrians can be done within the comprehensive plan or as a distinct pedestrian, active transportation, or multimodal plan that is adopted as an addendum to or in addition to and in alignment with the comprehensive plan.

Common elements for pedestrian planning, in addition to general planning elements, include:

- Establish existing conditions with data.

- Self-evaluations done for the ADA can contribute to this baseline data. Although the ADA does not require sidewalks, sidewalks must meet ADA requirements where they exist.

- Existing conditions should also include:

- Safety and crash data

- Identification of key destinations

- Existing network deficiencies

- Prioritize actions to take with policies, programs, and projects. This may include:

- Prioritized pedestrian networks or high-priority gaps to address

- Supportive land use and zoning changes that are needed, including pedestrian overlay districts to support design for more pedestrian-oriented environments

- Decide how to monitor progress and accountability in plan implementation.

Complete Streets

Complete Streets describes an approach to transportation planning, design, construction, maintenance, and operations that considers the needs of all potential users of all ages and abilities as they travel along and across roads and through intersections. Potential users include, but are not limited to, pedestrians, bicyclists, electric scooter riders, transit riders and transit vehicles, freight trucks, emergency vehicles, and drivers. Adopting and implementing local Complete Streets policies at the city or county level benefits all travelers and is particularly impactful for pedestrians. Complete Streets also supports a Safe System Approach through implementation for safer roads and safer speeds.

As a resource, the National Complete Streets Coalition routinely reviews Complete Streets policies nationally and publishes the best policies along with the elements of a strong policy framework. The main elements of a strong Complete Streets policy, according to this framework, include:

- Establishes commitment and vision

- Prioritizes underinvested and underserved communities

- Applies to all projects and phases

- Allows only clear exceptions

- Mandates coordination with government departments, partner agencies, and private developers

- Adopts excellent design guidance

- Requires proactive land-use planning

- Measures progress

- Sets criteria for choosing projects

- Creates a plan for implementation

In future planning work, the Met Council plans to develop a Complete Streets typology that will develop a guide for regional transportation partners to implement Complete Streets elements in their projects. This work will provide the region with recommended actions for incorporating and incentivizing Complete Streets elements in its project scoping and selection processes. Typology can be thought of as an overlay on functional classification, describing Complete Streets contextualized by land use and the functions of different mode choices.

Pedestrian project selection – regional investment guidance and key factors

Baseline requirements

All public agencies must have a current ADA self-evaluation that covers the public rights of way for transportation, as required under Title II of the ADA. Agencies with 50 or more employees must also have a transition plan, not just a self-evaluation. Public agencies that do not meet this requirement are ineligible to apply for Regional Solicitation funding in any category. (Organizations that are not public agencies are not subject to Title II of the ADA and are exempt from this requirement.)

The Transportation Policy Plan requires that these transition plans are reviewed and updated regularly with a goal of full system compliance of removal of barriers no later than 2050. Earlier compliance is encouraged and supported. These plans assist with transitioning to barrier removal in compliance with the ADA. The plan’s horizon of 2050 will be six decades after the passage of the ADA in 1990. ADA requirements are the minimum that should be done, while policies in this plan call for the region to fully meet the needs of people with disabilities (discussed more in the universal design section above). To reach this plan’s goals and objectives of eliminating injustices and fully meeting the needs of people who have a disability, the region will need to work to address the minimums that have not yet been achieved after decades.

Agencies must also affirm that the owner or operator of a facility ensures it is maintained year-round for all modes, including pedestrians. The Federal Highway Administration clarifies that day-to-day maintenance responsibilities under the ADA include keeping the path of travel on pedestrian facilities “open and usable for persons with disabilities, throughout the year. This includes snow removal… as well as debris removal, maintenance of accessible pedestrian walkways in work zones, and correction of other disruptions.”136 The Federal Highway Administration’s Guide for Maintaining Pedestrian Facilities for Enhanced Safety provides more information on year-round maintenance.

Prioritization factors

There are important prioritization factors for regional investments in the pedestrian system. These factors, described below, include safety, connections to transit and destinations, barrier removal, continuity across communities, demand, equity, and Complete Streets. These factors are not listed in order of priority, which is generally determined through investment processes.

Safety

Safety is a key priority for the region, with an emphasis on reducing fatal and serious injury crashes while maintaining and improving the convenience and comfort of walking and rolling. Investments should prioritize countermeasures for pedestrian safety that address crossing streets, not just traveling along them. Prioritization factors should also address motorist speeds, which are critical for pedestrian safety.

Evaluation criteria should prioritize consideration of risk factors for pedestrian exposure and location characteristics based on data analysis, such as what was done in the Regional Pedestrian Safety Action Plan. Addressing locations identified as having historical fatal and serious injury crash challenges or documented high risk areas should be considered in addition to risk factors. Only focusing on historical crash locations is a limited approach to proactively addressing safety on a systemic level. Projects should prioritize improvement locations based on close proximity (in other words, within 500 feet) to known pedestrian generators, such as transit stops, schools, community centers, housing (especially multifamily or affordable), shopping, dining, or entertainment destinations.

The Regional Safety Action Plan update, expected to be complete in 2024, will identify high-injury streets for pedestrians, in addition to bicyclists and motorists, on all roads in the region with the exception of freeways. This high-injury street identification may be used to prioritize investments along with identified risk factors for systemic improvements across the network.

Connections to transit

Independent pedestrian projects should prioritize facilities and improvements that connect to transit service. This includes:

- Pedestrian safety-focused improvements with a focus on safer crossings within 500 feet of an existing transit stop (whether local bus stops, or bus rapid transit or light rail stations). Almost 80% of severe (fatal or serious injury) intersection crashes for pedestrians between 2016 and 2019 were within 500 feet of a transit stop.

- Connecting to existing or potential high-frequency transit service.

- Transit-oriented developments around existing or programmed transitway stations.

- Existing transit stations, centers, or frequent service park-and-ride locations that are within reasonable walking distance to residential development, activity centers, or metropolitan job concentrations such as downtowns and the University of Minnesota.

The Work Program for this plan includes a project, Safer Connections to Transit, to better understand the relationship between pedestrian safety and transit, including strategies to improve the relationship.

Connections to destinations

Independent pedestrian projects should prioritize connections with job concentrations at different levels as identified in the Imagine 2050 Regional Development Guide. These job concentrations include other destinations important for people to be able to reach by walking, including grocery stores, libraries, schools, government services, shopping and daily needs. Pedestrian facilities done as part of larger transit or roadway projects should ensure the work facilitates these connections.

Barrier removal

Projects that are specifically identified as priorities in a community’s ADA transition plan should receive favor in consideration for removing barriers. Barriers can include, but are not limited to, pedestrian facilities that are not wide enough, are obstructed by utility poles or other items, have unacceptable slopes or conditions, or lack curb ramps with detectable warning surfaces. Projects that demonstrate best practices in design for use by people of all ages and abilities should also be prioritized. Highways and gaps in pedestrian networks are also barriers.

Continuity and connections across communities

Prioritization should favor projects that improve continuity and/or connections across communities. Creating more consistent and continuous facilities for walking and rolling improves access and the overall experience.

Complete Streets

Roadway projects should include elements that address all users of the transportation system, including people who are walking and rolling, no matter their ages or abilities. Roadway projects should emphasize safety and barrier removal for pedestrians. For roadway projects, independent pedestrian projects, or facilities shared with bicyclists within employment centers and connections to high-frequency transit service, the projects should emphasize support for compact, mixed-use, transit-oriented development.

Demand

Just like vehicle-count data, counts of pedestrians traveling on the system are important for baseline data. Having reliable data on traffic volumes and patterns for pedestrians is important for informing planning and engineering done at all levels. This data can be used to address traffic safety, health, economic development, and environmental goals.

However, counts of people currently walking or rolling are not enough to determine pedestrian demand. As an example, in locations where pedestrian facilities are not provided or are insufficient, counts will not reflect the need. To better assess pedestrian demand, tools can be developed to identify areas where pedestrian needs may be greater. MnDOT developed the Priority Areas for Walking Study as part of the Statewide Pedestrian System Plan to highlight areas that are important for walking. This work was based on the same unit of analysis that MnDOT also uses in its publicly available Suitability for the Pedestrian and Cycling Environment (SPACE) tool, which helps identify, select, and prioritize pedestrian and cycling facility projects. Both processes use an index of 19 social and demographic factors to calculate scores for half-mile hexagons throughout the state. Higher scores indicate latent demand for pedestrian and bicyclist facilities. This tool may be useful at the regional and local levels. Future Met Council work will look at this MnDOT tool and other options for estimating latent demand for pedestrians throughout the region. Other factors, such as land use, can help identify latent demand.

Equity

This is generally addressed separately when prioritizing projects, but equity is especially important to consider for pedestrians because of the disparities found in fatal and serious injury crashes in the data reviewed in the Regional Pedestrian Safety Action Plan. These disparities include higher rates of fatal or serious injury crashes for Black or American Indian residents and people with disabilities.

Funding programs

Pedestrian infrastructure can be funded from programs at the federal, state, regional, and local levels.

Federal programs

The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law created new federal funding programs for walking facilities and improved safety for pedestrians, in addition to continuing existing programs that provide funding for pedestrian infrastructure.

Safe Streets and Roads for All

This new federal discretionary funding program provides $5 billion in grants over a five-year period from 2022 through 2026 to prevent roadway deaths and serious injuries. The program funds planning and demonstration activities and implementation grants to carry out activities identified in a comprehensive safety action plan. In the initial rounds of funding in this program for 2022 through 2024, local jurisdictions in the region received grants directly from the federal government to create comprehensive safety action plans, including Hennepin County and the cities of Apple Valley, Bloomington, Brooklyn Park, Columbia Heights, Cottage Grove, Eagan, Edina, Elk River, Fridley, Hastings, Hopkins, New Brighton, St. Louis Park, Shakopee, West St. Paul, and Woodbury. The cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul have received grants from this program for implementation of safety improvements.

Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Program

This federal discretionary funding program combines two grant programs: the Reconnecting Communities Pilot and the Neighborhood Access and Equity program. These direct federal grants can be used for building or improving Complete Streets, as well as other activities focused on connecting communities who have been cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure such as highways. To date, the region has received grants from this program for planning for a land bridge and African American Cultural Enterprise District in the Rondo neighborhood of Saint Paul and for planning for Olson Memorial Highway/Minnesota Highway 55 in Minneapolis to reconnect communities along the route.

Highway Safety Improvement Program

This existing federal formula funding program is continued in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law at increased funding levels and can be used for pedestrian safety improvements, among other modes. The focus of this funding program is to reduce and prevent fatal and serious injury crashes on all public roads. This funding is allocated to MnDOT, and the region’s process is done in partnership with the Met Council and the Transportation Advisory Board (TAB). Applications are submitted to MnDOT, who runs the selection committee review of applications. The TAB and Met Council approve projects to receive this funding.

The federal law requires that states where pedestrians and bicyclists are more than 15% of all traffic fatalities use a minimum of 15% of their highway safety improvement funds for infrastructure improvements for the safety of these modes. This federal requirement is applied on a statewide, rather than a regional, basis. However, it is important to note that the 2024 solicitation for this program indicated 24% of the fatal and serious injury crashes in the region from 2018 through 2022 involved a pedestrian. Action 10G in the Policies and Actions chapter calls for the region to ensure that it is distributing funds for pedestrian and bicyclist safety in proportion to the percent of all pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities and serious injuries.

State programs

Safe Routes to School

Minnesota has used state funds from the general fund for Safe Routes to School since the state legislature created this program in 2012. This program has funded both noninfrastructure programs and infrastructure projects to support students walking and biking to school. This state funding is in addition to Safe Routes to School being an eligible activity for federal funding as part of the Transportation Alternatives set-aside of the Surface Transportation Block Grant program.

Statewide Health Improvement Partnership (SHIP)

Created in 2008 by the Minnesota Legislature, this state program administered through the Minnesota Department of Health provides $35 million every two years to support critical primary prevention activities led by local public and Tribal health partners. Active living is one of the emphasis areas for locally driven solutions to help prevent chronic diseases, and communities can use this funding to help make it easier to walk and bike.

Active Transportation Program

The Active Transportation program was created by the legislature in 2018 and initially funded with $5 million in 2021. This competitive grant program is administered by MnDOT to improve conditions for walking, biking, and rolling. Grants are provided to local agencies for active transportation technical planning assistance, education and encouragement programs, engineering studies, and infrastructure investment. In 2023, for the first time, MnDOT did not allow metro-area projects to apply for this funding.

Regional programs

Regional Transportation Sales and Use Tax for Active Transportation

The 2023 Minnesota Legislature created a new revenue source for the region’s transportation system with a three-quarter-cent sales tax that began in the region in October 2023. The proceeds from this sales tax will be split between the Met Council, which will receive 83%, and the seven counties in the region, which will receive 17% (referenced in the other state and local funds section below). For the Met Council’s portion, 5% will be for active transportation (in other words, walking, biking, and rolling). Approximately $24 million is estimated to be available for active transportation projects annually from the Met Council’s share alone. The Met Council’s funding will be programmed through the TAB and must meet the requirements outlined in state law.

Regional Solicitation

The Met Council, through the Regional Solicitation process, programs federal transportation funds from different programs, including the Surface Transportation Block Grant program, the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality program, and the Transportation Alternatives Program that is part of the Surface Transportation Block Grant Set-aside Program. The Regional Solicitation process currently includes three primary application categories: roadways, including mode-choice elements; transit and travel demand management projects; and bicycle and pedestrian facilities. Pedestrian projects can be funded from any of these federal programs within the limitations of the functional classification requirements for roadways.

Current federal law makes about $250 million available through the Regional Solicitation every two years. Bicycle and pedestrian facilities applications historically have received a range of 9% to 20% of the total available funds (around $22 million to $50 million every two years). Facilities for pedestrians may be included in the three application categories for bicycle and pedestrian facilities: Safe Routes to School infrastructure projects; pedestrian facilities; and multiuse trails and bicycle facilities (since multiuse trails serve both pedestrians and bicyclists). Facilities for pedestrians may also be funded as part of roadway and bridge projects that are funded in separate application categories. The Regional Solicitation evaluation work program item will direct how pedestrian projects are funded starting with the 2026 Regional Solicitation.

Carbon Reduction Program

The region received federal Carbon Reduction Program formula funds that can be used for pedestrian facilities. Specific funding categories and criteria for this program will be determined through the Regional Solicitation evaluation Work Program item to inform the 2026 Regional Solicitation. Current federal law makes about $14 million available through this program, which provides funds for five years from 2022 through 2026.

Federal law requires each state to develop a State Carbon Reduction Strategy to support efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from on-road highway sources in consultation with metropolitan planning organizations in the state. MnDOT published a report documenting the state’s strategies and goals in November 2023.

Other state and local funds

State highway funds pay for some pedestrian facilities on the state highway system, often as part of larger roadway projects. MnDOT plans specifically for accessible pedestrian infrastructure as a category within the State Highway Investment Plan, among others that address pedestrian needs.

Local funds from counties, cities, and park agencies are also critical to development of pedestrian facilities. These funds are typically provided from property taxes but may also come from sales taxes. Like MnDOT, counties and cities may also use their roadway state-aid revenues from the state gas tax to fund pedestrian facilities as part of overall roadway and bridge reconstruction projects on their state-aid roads.

Counties will also have funds available from the Regional Transportation Sales and Use Tax for Active Transportation that can be used for active transportation (walking, biking, and rolling) projects. The legislature also required at least 41.5% of the counties’ share of the sales tax to be used for active transportation projects or safety studies. This is a significant new funding source for projects focused on people walking, biking, or rolling that will be programmed at the local level.

An official website of the

An official website of the