Transportation Overview

Table of Contents

Introduction

The core purpose of transportation is providing people and businesses access to the places they need to reach, and choice in how to reach these places. People and businesses need reliable transportation choices so they can perform everyday tasks, like taking a child to daycare, going to work, attending school, or delivering goods and services. These needs and places are unique to each resident and business in the Twin Cities region, and this plan’s challenge is to better meet those needs across a growing region with diverse community contexts.

By 2050, the Twin Cities region will add 657,000 new residents and 342,000 new jobs.

Footnote: 1

The COVID-19 pandemic was a shock to regional transportation and land use systems, and our regional transportation system is still adapting in response. While the way some people live and work has changed, our fundamental need to travel to meet daily needs remains. Some of the lasting effects are positive, like time savings from reduced congestion during peak commute hours, while others are negative, like worsening traffic safety outcomes and revenue challenges for transit.

Investments and legislation at the state and federal level are key in addressing this growth and change. In 2023, the Minnesota Legislature provided transportation revenue increases, including the gas tax, vehicle registration tax, motor vehicle sales tax, and state general funds. They also included new transportation revenue sources, most notably a new seven-county metro regional sales tax for transit, active transportation (walking, biking, rolling), and county transportation.

In 2021 and 2022, Congress created many new programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve transportation resilience to climate change, including new sources of regionally allocated revenues for each. The Biden-Harris administration has undertaken multiple actions in pursuit of environmental justice and improved transportation equity. The Justice40 Initiative, established by Executive Order 14008, aims to direct 40% of federal investment benefits to disadvantaged communities, encompassing programs like Carbon Reduction and Safe Streets and Roads for All. The administration also updated the definition of environmental justice to include people with disabilities, functioning alongside existing orders on environmental justice.

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan presents the region’s objectives, policies, actions, and investments that guide development of the region’s transportation system. It implements the core values, vision, and goals of Imagine 2050: Our Region’s Plan for an Equitable and Resilient Future. Integrated with updates to regional plans guiding land use, water resources, housing, and parks policy, the Imagine 2050 family of plans will create a prosperous future for our children and grandchildren.

As the region’s federally designated metropolitan planning organization, the Metropolitan Council prepares a transportation plan for all forms of travel in the region. This transportation plan and other Met Council plans are prepared with input from many sources, including the region’s counties, cities, and towns, which use these plans as a guide in their own planning processes. The Met Council’s planning region includes Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties. As required by federal law, the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan also plans for urban portions of southeast Sherburne and Wright counties.

The regional transportation system

Highways

Each day, 86% of all trips in the region are taken in an automobile.2 These roads also serve freight, transit, walking, biking, and rolling. Roads are a key part of a dynamic and resilient transportation system, and the regional highway system is its backbone. While only representing about 16% of centerline road miles in the region, this system carries 80% of all vehicle miles traveled. It includes:

- Principal arterial highways: interstates, other freeways, and expressways and certain major roads (for example, Cedar Avenue in Lakeville). The region has 700 miles of principal arterial highways primarily owned by the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT). These roads carry 8% of bus service in the region.

- Minor arterials: roads that aren’t as fast as principal arterials but still serve many trips. These roads provide direct routes and some local access, often serving transit, walking, and biking trips, too (for example, Snelling Avenue in Ramsey County). The region has 2,300 miles of minor arterial roads owned 72% by counties, 16% by MnDOT and 12% by cities. These roads carry 51% of bus service in the region, and they also serve as the first- and last-mile connections between freight-generating businesses and principal arterial highways.

Improving safety on this system, and on collector and local streets, was strongly emphasized by technical stakeholders and policymakers during plan development. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, safety performance regressed and more people in our region died or were seriously injured while traveling on roadways. In 2022, 179 people did not make it home after a crash in the Twin Cities region. This plan seeks to eliminate these fatal and serious injuries from traffic crashes by 2050 through implementation of the Safe System Approach.

These highways are a key economic driver in our region. In 2020, delay per commuter in the Twin Cities was comparable to other similarly sized metropolitan areas across the nation.3 In 2021, the region had the ninth-highest job accessibility by vehicle in the United States,4 and has consistently been ranked in the top ten for several years. However, the region must continue to address excessive travel delays to retain our high standard of living and regional economic competitiveness.

See the Highway Investment Plan for more information about our existing regional highway system and planned investments.

Transit

Transit is an essential means of travel for many residents in the region. On a typical weekday in 2023, people in the Twin Cities region took more than 135,000 rides on public transit services. Transit services are, for people who cannot drive, a reducer of greenhouse gas emissions through more efficient travel and a congestion mitigator.

Together these providers served 53.3 million rides in 2023, or about 16.2 trips per person in the region.

The region is served by six transit providers: the Met Council (Metro Transit and Metropolitan Transportation Services), the Minnesota Valley Transit Authority, SouthWest Transit, Maple Grove Transit, Plymouth MetroLink, and the University of Minnesota. Together, they operate a variety of services that include regular route buses, bus rapid transit, light rail, commuter rail, dial-a-ride and paratransit, microtransit, and vanpool.

Total ridership increased 16% in 2023 over the previous year, showing encouraging signs of ridership recovery from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. To serve these riders, the six regional transit providers ran 3.7 million hours of transit service in 2023, or about 1.2 hours per person.

The total area served by transit (within a half mile of a transit stop) in the region was 492 square miles. About 55% of the region’s population lived within a half mile of regular-route transit services, and 19% lived within that same distance of high-frequency transit (meaning a transit vehicle departs at least every 15 minutes from a stop). Roughly 50% of the region’s jobs were located within a half mile of a transit stop as well.

See the Transit Investment Plan for more information about our existing transit system and planned investments.

Bicycles

The Twin Cities region has a well-developed bicycle network throughout much of the region, including:

- Regional trails designated in the Regional Parks Policy Plan and developed and maintained by regional park implementing agencies.

- Local bikeways and off-road multiuse trails that cities, counties, and MnDOT are responsible for planning, developing, and maintaining.

- Several state trails in the metro region developed and maintained by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

In 2016, the Met Council measured the size of this system in the Regional Bicycle System Inventory, which identified 3,908 miles of existing bikeways and 2,865 miles of planned bikeways. Over time, the region’s investments in bicycle-friendly infrastructure have led to Minneapolis and Saint Paul consistently ranking in the top 10 best large cities for biking, as rated by PeopleForBikes, a nonprofit bicycle policy and trade organization. Work remains to expand this option throughout the region.5

Local governments are the key drivers of building this system, and they face constrained resources to build connected networks for transportation. Through several regional studies, the Met Council created three planning and investment prioritization tools to guide regional investments:

- The Regional Bicycle Transportation Network (RBTN) establishes an integrated, seamless network of bikeways and trails to prioritize investments that serve daily trips, provide access to destinations, and connect local bicycle networks.

- The Regional Bicycle Barriers identifies major physical barriers to bicycling (for example, freeways, railroads) and identifies barrier-crossing opportunity areas.

- The Major River Bicycle Barrier crossings identify investment priorities for providing connections across the region’s three major rivers: the Mississippi, Minnesota, and St. Croix Rivers.

See the Bicycle Investment Plan for more information about our existing bicycle system and planned investments.

Pedestrians

Walking is our most universal mode of travel – we all walk or roll (using a mobility device such as a wheelchair or walker) and walking also makes essential connections to other modes of travel. Across the region, nearly 11% of all trips were walking-only trips.6

Walking is an essential means of travel within the regional transportation system, but availability, type, and quality of facilities for walking vary across the region. Facilities for walking include a few state trails in the metro, regional trails (as designated in the Met Council’s Regional Parks Policy Plan), local multiuse paths, sidewalks, skyways, and pedestrian or multiuse bridges or underpasses. Often the most dangerous part of walking or rolling is crossing streets, so street-crossing treatments are critical parts of infrastructure for safe travel by people walking and rolling.

See the Pedestrian Investment Plan for more information about our existing pedestrian system and planned investments.

Travel Demand Management

Travel demand management is a set of strategies and investments that the region makes to reduce the need to invest in infrastructure and to support other regional goals by encouraging travel behavior changes. Travel demand is influenced by the availability of transportation infrastructure and services, land development patterns, and personal travel needs. Many partners play a role in influencing these three factors, but the primary implementors of travel demand management strategies use engagement, incentives, and promotions to influence travel demand. Implementors like transit providers and transportation management organizations work directly with travelers or through employers to tailor programs to specific needs with the intent of shifting to modes other than driving alone or shifting travel to nonpeak times. Travel demand management strategies are often coupled with new infrastructure investments or with development practices implemented by city zoning codes.

See the Travel Demand Management Investment Plan for more information about the existing travel demand management strategies and opportunities for expansion.

Freight

The existing metropolitan freight system consists of several interconnected networks and regional freight terminals that facilitate the movement and transfer of freight within and between forms of freight transportation. These include trucks on highways, railroads, barges on rivers, air freight, and pipelines.

See the Freight Investment Plan for more information about our existing freight system and planned investments.

Aviation

The Twin Cities region boasts a well-developed and mature aviation system that does not require continued expansion, but rather requires ongoing protection, maintenance, and limited enhancements. The region is served by one major commercial air service airport, Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport (MSP), and its six reliever airports owned and operated by the Metropolitan Airports Commission. The region is also served by two other general aviation airports owned and operated by local governments. All MAC-owned airports are part of the National Plan of Integrated Airports (NPIAS), in addition to South St. Paul Municipal Airport. Additionally, there are two designated seaplane bases, many bodies of water that can support seaplane operations, and multiple private turf runways in the region.

Prior to the pandemic in 2020, MSP Airport reached a new record for passenger enplanements at 19.8 million with more than 36 million total passengers in 2019. These record numbers of passengers were moved in the fewest number of aircraft operations since 1992, a year which saw only 10 million passenger enplanements. In addition to passenger activity, MSP saw 239,544 metric tons of cargo moved through the airport in 2019. Unlike passenger activity, dedicated cargo activity saw a modest increase at MSP during the pandemic due in part to the shift to more online sales with retailers like Amazon. These retailers continue to show growth in air cargo and delivery operations.

The Aviation System Plan is currently under development.

Summary of regional transportation investments

The plan is fiscally constrained, meaning that the plan identifies all transportation revenues that can reasonably be expected and are assumed to be available within the plan’s time frame, together with the proposed spending of those revenues. Those assumptions are structured around four categories:

- MnDOT metro state highway revenues and spending

- Regional transit revenues and spending

- Local government transportation revenues and spending

- Regionally allocated revenues

In addition to describing transportation revenue and spending, this plan documents regionally significant projects, like addition of a freeway lane or building a new transitway. See the Investments section of this document for further detail on this plan’s financial assumptions and listing of regionally significant projects.

Evaluation and performance

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan uses a performance-based approach to measure success in meeting the region’s transportation goals and objectives. The measures will indicate where the region is meeting its transportation-related goals and objectives and what areas require greater emphasis and resources. The Met Council and its regional partners have selected performance measures that are clear, measurable, and closely tied to the plan’s goals and objectives.

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan includes two main performance measures categories. Federal Performance Measures are federally required, shorter-term targets that the Met Council must track and report on. Federal Performance Measures includes topics like safety, reliability, bridge and pavement conditions, and system performance and reliability. Regional Performance Measures are longer-term evaluations that the Met Council will use to track how well the regional transportation system is meeting the Imagine 2050 goals.

Plan structure

The Transportation Policy Plan is a section of the Imagine 2050 plan, an integrated plan for shared regional systems. The Met Council develops regional plans for land use, housing, parks, water, and transportation systems. These plans use a shared set of values, vision, and goal statements, detailed in Imagine 2050. Underneath these goal statements, the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan contains objectives for the regional transportation system, further defined by policies that state the intent and approach to regional issues and implemented through specific actions.

Fiscal constraint

Federal regulations require the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan to demonstrate that projects identified in this plan can be implemented using reasonably available revenue sources. Projects listed in this plan’s Long-Range Highway and Transit Capital Projects Lists represent the fiscally constrained elements in this plan, deliverable by existing revenue sources documented in Regional Transportation Finance. The fiscally constrained element of this plan cannot be aspirational about projects without identified revenue sources, nor can it make assumptions about discretionary grants or future legislative or congressional actions. However, this plan does illustrate potential projects that are part of a longer-term vision that the plan’s policies and actions could support; these projects are not formally part of this fiscally constrained plan.

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan is the region’s long-range plan for the region’s roadway, freight, transit, bicycle, pedestrian, and aviation systems. The plan is informed by the shared elements of Imagine 2050, state plans, system and corridor studies, and the conditions of funding programs. This plan receives a major update every 10 years, a minor update every five years, and specific amendments or modifications regularly as required by projects or policy change.

For investments that are federally funded or regionally significant, this plan informs the short-range planning process that develops the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). The TIP is issued annually and includes a rolling four-year cycle of programmed projects. TIP projects include major local projects, projects awarded federal funds through the Regional Solicitation or competitive federal grant programs, and projects programmed by regional transit providers or the Minnesota Department of Transportation using their federal funding allocations. The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan provides investment direction that informs the structure, criteria, and measures in the Regional Solicitation.

Throughout these steps, the Met Council regularly seeks feedback from policymakers, technical stakeholders, residents, businesses, advocates, and community groups from throughout the region. This feedback arises through the TPP and TIP development, planning studies that provide new information and approaches, and transportation investment processes as projects are planned, designed, built, and operated. This feedback, alongside performance measurement and evaluation, informs continuous improvement of the plan and its implementing programs and investments.

Figure 1.1: Metropolitan transportation planning cycle

Engagement and plan development process

The Met Council strategically approaches public participation to meet the needs of the region. It is important to reach out to stakeholders from all backgrounds and perspectives to have well-thought-out policies that benefit everyone. Public participation is done holistically and comprehensively with the practice of collaboration and inclusion.

The Transportation Addendum to the Public Engagement Plan establishes a framework for the region’s stakeholders to influence both long-term transportation policy development and short-term transportation programming. It details the methods and strategies that the Met Council will use to engage a wide range of stakeholders, from policymakers and business interests to residents of the region. It also identifies specific ways those stakeholders can connect to the transportation decision-making process.

Partner agency engagement

This plan was developed with the experience and perspective of implementing partners. The Met Council implements few projects itself other than transit projects, working in partnership with cities, counties, state agencies, and nonprofit organizations to deliver transportation projects. Engagement with these partners is key in developing all aspects of this plan.

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan Technical Working Group was formed underneath the Transportation Advisory Board’s Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) to assist with plan development and review. The Imagine 2050 TPP Technical Working Group consisted of 39 members, including all represented on the TAC’s Planning subcommittee (see Committee members), and additional members representing city, county, state, federal, nonprofit, and academic stakeholders. This group met 24 times over the course of two years to advise Met Council staff on engagement practice, setting goals and objectives, developing policies and actions, and drafting investment and goal-related plan narrative. The TAC received regular reports on Imagine 2050 TPP Technical Working Group discussion and seven informational presentations on development of Imagine 2050 plans since 2022.

The TAC, Imagine 2050 TPP Technical Working Group, Bicycle & Pedestrian Planning Technical Working Group, and Transit Planning Technical Working Group together provided over 2,600 comments on draft plan content in addition to in-meeting discussion.

Transportation Advisory Board

Providing a regional multimodal transportation system meeting the needs of many users requires coordinated planning among partners implementing the system. The Met Council works with its regional partners, including state agencies, cities, counties, and other stakeholders, to ensure regional transportation investments support the Imagine 2050 vision for the region, accommodate projected growth, and use public resources wisely and cost-effectively.

The Met Council serves as the federally designated metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the Twin Cities region. Congress created MPOs to ensure that decision making for federally funded or regionally significant transportation investments are based on a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive regional planning process.

The Met Council’s 16 members and chairperson are appointed by the Governor of Minnesota, a structure that predates current requirements that MPO governing boards include local elected officials, state and regional transportation agency officials, and transit agency officials. In our region, the Transportation Advisory Board (TAB), which was created under state statute to provide advice to the Met Council on regional transportation issues, serves as the conduit for local policymaker and agency input. TAB’s membership includes city and county elected officials, state and regional transportation agency leaders, and appointed citizens representing geographic districts and transportation modes. TAB is an integral part of the region’s transportation planning process and leads the solicitation, evaluation, and recommendation of projects funded with regionally allocated federal transportation funds.

Advisory Work Group

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan Advisory Work Group was formed under the Met Council to discuss key plan issues. It was a focused group of Met Council members, Transportation Advisory Board members, and leaders representing state and transit agencies. This group met 15 times over the course of two years to provide Met Council staff with regional perspectives and local context during development of objectives, policies, and actions.

Listening sessions and development workshops

The early work to gather deeper feedback from stakeholders started in early 2023 with a series of listening sessions and interviews. The purpose of these interviews was to reflect on the 2040 Transportation Policy Plan’s successes and limitations and learn about what issues were most pressing for the region’s transportation system. These engagement sessions were both transportation partner stakeholders and community-based stakeholders. The engagement ultimately led to draft Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan objectives that were then further discussed and refined within the broader plan development processes.

Once a working structure of goals and objectives were in place, the work began on drafting policies and actions. This was done through eight policy development teams structured around the plan’s goals and objectives. These teams include technical experts that made recommendations and reviewed content that eventually led to a draft list of policies and actions. This draft list was further shared with a wider audience of technical staff through a series of virtual and in-person workshops. The feedback from these workshops was used to create updated versions of the policies and actions that were then further discussed and refined within the broader plan development processes.

Community-based public engagement

Because the region is growing and the population is changing, public participation needs to be coordinated and deliberate. Those who have not been historically engaged in policy conversations with the Met Council are a key constituency and have been intentionally included in engagement for the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan.

In 2022, the Met Council initiated a three-year contract to support engagement with Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), Hispanic, low-income, and other traditionally underrepresented communities.

That contract has supported efforts that have directly impacted the development of the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan including the Regional Travel Demand Management Study, the Transportation Needs in Daily Life Study, and the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan Goals, Objectives, Policies, and Actions.

Approaches

Each effort took different approaches to engaging traditionally underrepresented communities, including:

- Community events and intercept surveys

- Online surveys

- One-on-one and small group interviews

- Listening sessions

- Small group discussions

In community-based public engagement, we strive to prioritize quality over quantity. This creates deeper, more meaningful interactions that foster genuine connections and long-term commitment. The true value lies in the richness of the engagement, where individuals feel heard, valued, and actively involved. High-quality interactions build trust and collaboration. Quality-driven engagement is essential for nurturing resilient and vibrant communities.

Engagement on the Imagine 2050 TPP goals, objectives, policies, and actions

We broke this engagement into two phases, connecting with as many of the same groups and individuals as possible to create continuity across these areas that ground the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan. Phase 1 focused on the goals and objectives and phase 2 focused on the policies and actions.

Phase 1 engagement resulted in five themes to consider as we developed the goals and objectives.

- Equity is a top priority for many, but it needs to be more clearly defined.

- Safety is viewed by most community members as transit, rather than all modes.

- System maintenance brought up tensions between investing in existing infrastructure versus transforming for the future.

- Elevate climate change above and beyond naming climate in the Imagine 2050 vision.

- A multi-node future where community members imagine a future of many regional nodes.

Phase 2 engagement followed up with the proposed policies and actions and asked for community groups and individuals to respond and react. These themes emerged from community-based conversations.

- The housing / transportation connection is important and would benefit from explicit acknowledgement.

- Going deep on equity is seen as important to making progress on achieving the Imagine 2050 goals.

- Balance behavior change with technology change in the proposed policies and actions instead of relying on technology.

- Successful implementation relies on effective coordination across jurisdictions and sectors.

This engagement was all done ahead of drafting the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan, so the themes could be considered when drafting the content.

Study-level engagement

This valuable community input influenced and helped shape the foundational elements of the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan, while engagement at the study level brought a community-based lens to key study areas.

In particular, the Transportation Needs in Daily Life project brought forward community voices in a unique and impactful way. Participants’ willingness to share their personal stories has created a deeper understanding of the regional transportation system and, more broadly, of how to work better with our communities. We recognize that we must, in turn, share their stories in the most true and meaningful ways we can while making the feedback actionable.

Contributing plans and studies

The region uses statewide plans and regional planning studies to inform the policy direction and investment plans for the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan. This is part of the continuing planning process required under federal law. Regional planning studies typically explore a specific topic in detail and provide recommendations for consideration in the Imagine 2050 TPP development related to content like policies and actions, investment plans, performance evaluation, and project lists. These studies are regional in nature and are in addition to corridor-level or subregional planning work completed by regional implementing partners, which are not summarized here. Most of these contributing plans and studies include engagement with technical stakeholders as well as some engagement with policy stakeholders and community-based stakeholders. The following studies contributed to this plan development:

- Minnesota Statewide Multimodal Transportation Plan (Updated 2022)

- Minnesota State Highway Investment Plan (Updated 2023)

- MnPASS System Study, Phase 3

- Congestion Management Safety Plan, Phase 4

- Freeway System Interchange Study

- Twin Cities Highway Mobility Needs Analysis

- Intersection Mobility and Safety Study

- Congestion Management Process Policies and Procedures and Corridor Analysis Handbook

- Functional Classification Process Update

- Regional Safety Action Plan

- Urban Freight Distribution Study

- Transit Service Allocation Study

- Metro Transit Network Next Arterial Bus Rapid Transit Study

- Mobility Hub Planning Guide

- Regional Bicycle Transportation Network (RBTN) Bicycle Facility Guidelines and Measures

- Regional Bicycle Barriers Study

- Regional Truck Highway Corridors Study and Update

- Pedestrian Safety Action Plan

- Regional Travel Demand Management Study

- Electric Vehicles Planning Study

- Regional Transportation and Climate Change Multimodal Measures Study

- Travel Behavior Impacts of COVID-19

- Travel Behavior Inventory and On-Board Survey Programs

- Transportation Needs in Daily Life Study

- Maximum Mode Shift, a Vehicle Miles Traveled Reduction Study

- Equity Evaluation of Regional Transportation Investments

The plan also identifies new planning studies in the Work Program to start in 2024 and beyond that will inform future Transportation Policy Plan updates.

Public comment period

The Met Council released the Transportation Policy Plan for public comment on Aug. 15, 2024, and comments were accepted through Oct. 7, 2024, alongside Imagine 2050 and other system and policy plans. The Met Council held a public hearing to accept comments on the plan on Sept. 25, 2024.

We received approximately 400 comments on the Transportation Policy Plan, including comments substantively related to long-range transportation planning that were submitted about other Imagine 2050 plan sections. Met Council staff reviewed each comment, considered and made responsive changes, and provided responses. These changes were widely distributed to policy and technical stakeholders who participated in the Transportation Policy Plan development prior to considering its adoption. A summary of major themes and complete listing of comments and responses are available in the plan’s public comment summary.

Amendments and updates

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan can be amended and is required to be updated at least every five years under federal law.7 The next interim five-year update ahead of the 2060 plan update is planned to be a minor update that maintains the general plan goals and objectives but updates any necessary policy direction, finance assumptions, actions, and work program.

Amendments and administrative modifications to the plan will be posted as separate documents that are self-contained with all the relevant information, so please check the Met Council website for any amendments or administrative modifications to this plan after its adoption. The following are examples of what is addressed in each type of plan change.

- Update: Inclusion of substantial policy direction modifications that will likely impact the fiscally constrained plan, including the incorporation of major revenue assumption updates and new funded project lists.

- Amendment: Addition or substantial change of any regionally significant project that is not selected through the Regional Solicitation process (see the Long-Range Highway and Transit Capital Project Lists for definitions). Inclusion of new revenues that do not substantially alter the policy direction of the plan but do impact the long-range project lists.

- Administrative modification: Inclusion of illustrative projects that are not included in the fiscally constrained plan. Updates to maps, figures, or policy direction that do not impact the fiscally constrained plan.

Approach to Regional Goals

The following sections describe the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan approach to the regional goals. The discussion on each goal includes the following sections: objectives, performance measurement, policies, work program, major topics, recent work, and examples of supporting work by partners.

Read the about the Regional Goals

Browse Transportation Objectives

Our region is equitable and inclusive

Equity is embedded in Imagine 2050 at different levels: as a value, as a goal, and in transportation specific objectives in the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan. Values are core beliefs or principles that guide the Met Council's work, our expectations of partnerships, and our policy and program development. The Met Council has identified equity in a core set of values that we believe are most important to the issues and opportunities that face the region, now and into the future:

Equity means that we value the people and communities of our region. Our region is economically and culturally vibrant. However, we recognize the harm and disparities that systemic injustices, including racism, have created.

We are dedicated to creating systems, policies, and programs that repair and heal past harms, foster an equitable future, and eliminate disparities. People in communities that historically and currently experience marginalization will be centered in this work in leadership roles.

Objectives

- Historically disadvantaged communities are better connected to jobs, education, and other opportunities.

- We repair and eliminate disparate and unjust impacts and harms to Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color.

- We better meet the transportation needs of people who have disabilities or limited mobility.

Performance measurement

Performance measures help evaluate how well the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan is addressing the region’s goals and objectives, as defined in this plan and Imagine 2050. The measures used to track performance for equity and inclusion in this plan are access to destinations, exposure to pollution, exposure to noise, and exposure to extreme heat. More on these measures can be found in the Imagine 2050 TPP Evaluation and Performance section.

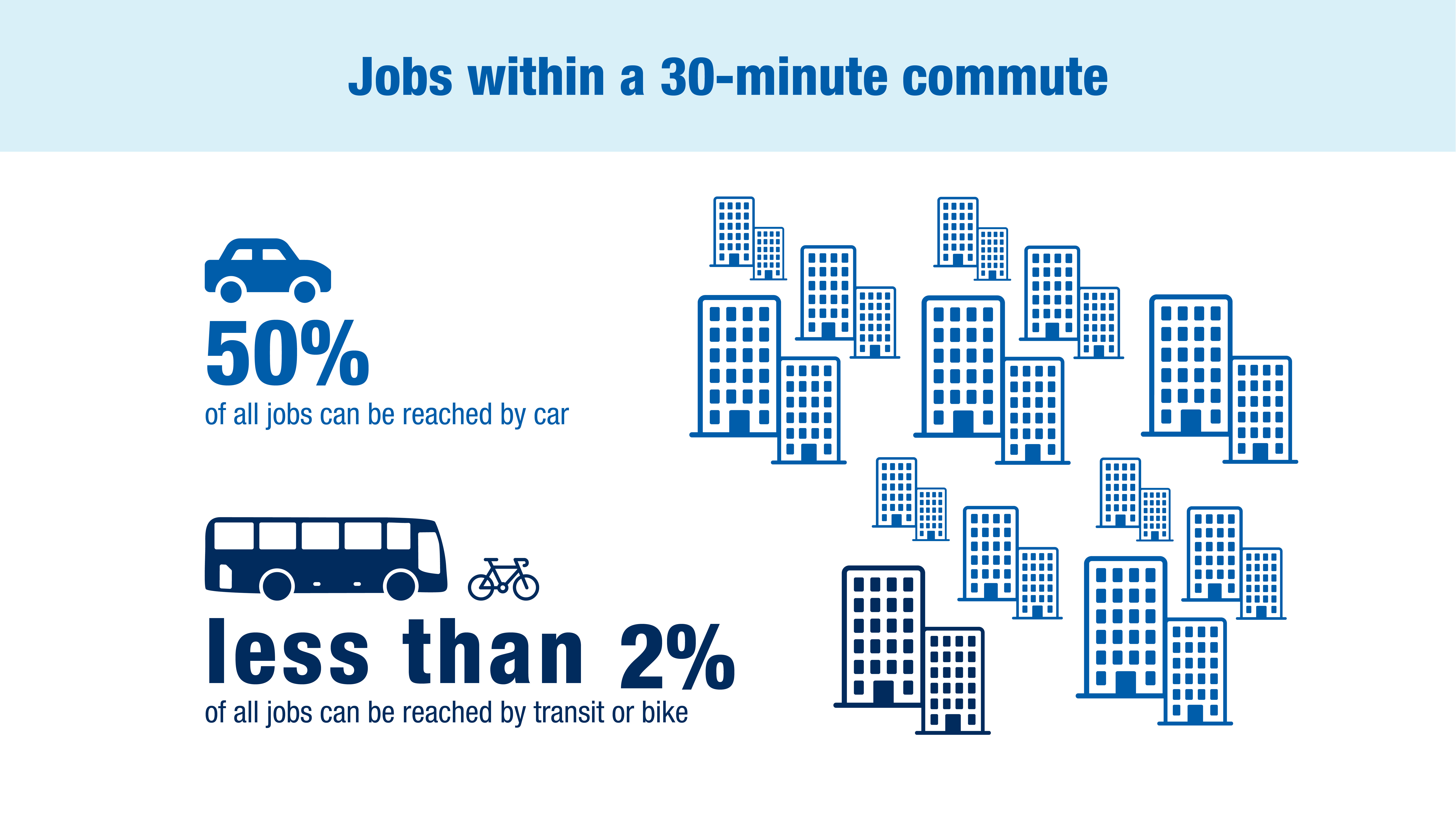

Improving access for all modes (including alternatives to driving) is one step towards a more equitable and inclusive region. Automobiles currently offer the highest job accessibility by a large margin. The average resident can reach 50% of all jobs in the region in 20 to 25 minutes by car during the morning commute. By contrast, less than 6% of the region’s jobs can be reached by bike and transit in an hour. The transit investments in the 2050 Transportation Policy plan are expected to increase transit accessibility by 15% in 2050.

Performance measures also show that exposure to air pollution, noise, and extreme heat are often highest along heavily used roads and highways. Under existing conditions at least, these are frequently areas with higher percentages of low-income households and people of color. How policies influence the location and intensity of traffic on these facilities going forward will also influence the equity of our transportation network.

Policies

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan sets five policies related to transportation equity and environmental justice. These policies and their supporting actions are detailed in Policies and Actions.

Policy 4. Conduct engagement activities and implement shared decision making with historically underrepresented communities throughout policy making, planning, and project development to ensure equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of transportation investments.

Policy 5. Ensure communities and investments meet federal Americans with Disabilities Act standards and encourage partner government agencies to go above minimum standards to fully meet the needs of people who have a disability in infrastructure, services, communication, and engagement.

Policy 6. Implement strategies against gentrification and displacement caused by transportation investments.

Policy 7. Evaluate processes, policies, programs, and plans to ensure that community benefits and burdens from transportation investments are distributed equitably.

Policy 8. Implement investments that repair harms and impacts to historically underrepresented communities from past highway investments.

Additional policies or actions may be amended into the plan after the completion of work in progress from the Equity Evaluation of Regional Transportation Investments study or the upcoming Metropolitan Highway Harms study.

Work program

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan identifies the specific work program items related to this goal area. More information on these items can be found in the work program.

The Metropolitan Highway Harms Study will identify and address the long-term harms caused by Minnesota's Metropolitan Highway System and propose mitigation investments for inclusion in the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan. Additionally, the Transportation Project Impacts to Disadvantaged Communities project aims to develop a methodology for assessing the benefits and harms of transportation projects on various demographics, addressing federal requirements such as environmental justice and Justice40, and incorporating community guidance to inform transportation policy and funding decisions. Finally, the Community Assessment and Project Public Engagement Guide, building on the Equity Evaluation of Regional Transportation Investment Processes Study and the framework and tool it produced, will provide a framework for early community engagement, ensuring equitable distribution of transportation benefits and burdens by mapping community assets, defining communities, and integrating their transportation needs into project planning, development, and decision making.

Major topics

Equity and inclusion are framed by several important concepts described below, including an equity definition for Imagine 2050, a racial equity framework, environmental justice framework, federal regulatory context, and past and ongoing transportation-related harms.

Equity definition

Imagine 2050 includes the following definition for equity:

Equity at the Met Council means that historically excluded communities – especially Black communities, Indigenous communities, and communities of color – have measurably improved outcomes through an intentional and consistent practice of adapting policies, systems, services, and spending so that they contribute to the repair of both historic and ongoing injustice.

Figure 1.2: Met Council racial equity framework

Racial equity framework

The Center for Urban and Regional Affairs at the University of Minnesota has used a racial equity framework to guide its work with communities and other stakeholders. The Met Council supports the continued use of this framework through Imagine 2050. The framework represents the Met Council’s commitment to the regional equity goal and value statement. It also provides expectations for how equity should be expressed and visible in policy language for the Met Council.

Environmental justice framework

The Met Council’s environmental justice framework, discussed in more detail in the Our Region is Equitable and Inclusive section of Imagine 2050, defines environmental justice as the right for all residents to live in a clean, safe environment that contributes to a healthy quality of life.

Environmental justice centers, but is not limited to, Black communities, Indigenous communities, communities of color, disabled communities, immigrant and refugee, and low-income communities who have and continue to experience a legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers that have resulted in environmental injustices, harms, and risks.

Through its regional values, the Met Council commits to conducting community-centered engagement, repairing past and ongoing harms, distributing benefits equitably, and preventing future burdens. Environmental justice at the Met Council requires necessary adaptations to Met Council services, requirements, policies, practices, processes, and decisions, starting with Imagine 2050, to support a healthy and safe region.

Federal regulatory context

The Biden-Harris administration undertook multiple equity-related actions, starting with the U.S. Department of Transportation's Equity Action Plan, which was released in January 2022 in response to Executive Order 13985. The plan focuses on expanding access to affordable transportation, supporting small, disadvantaged businesses, increasing community input in transportation decisions, and boosting federal equity investments. The Justice40 Initiative, established by Executive Order 14008, aims to direct 40% of federal investment benefits to disadvantaged communities, encompassing programs like Carbon Reduction and Safe Streets and Roads for All. Executive Order 14096 updated the definition of environmental justice to include people with disabilities; this order functions in tandem with the earlier Executive Order 12898 on environmental justice. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act ensures nondiscrimination in federally funded programs based on race, color, and national origin, and the Rehabilitation Act and the ADA protect the rights of people with disabilities. The U.S. Department of Transportation's 2022 Disability Policy Priorities emphasize multimodal accessibility, job access, vehicle accessibility, and robust enforcement of disability laws. More information on these federal initiatives can be found in the Environmental Justice section.

Past and ongoing transportation-related harms and need for action

The Met Council acknowledges the transportation system created by government decisions has excluded, unjustly harmed, and displaced some communities, and that many of these harms continue today. People who have suffered from a legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers include Black communities, Indigenous communities, communities of color, and people who have disabilities. Transportation should connect people to each other and meet their daily needs. Yet for some communities, transportation, or in some cases the lack of it, has created disconnection from destinations and formed barriers within communities.

This plan acknowledges these effects and pairs them with actions to address these injustices and create beneficial connections for these communities.

Race and transportation

Broader discrimination in society plays out in our transportation system along with other areas such as housing. Black people, people with disabilities, people of color, and people living in poverty have their own intersecting histories of erasure, discrimination, and disproportionate impacts related to transportation. As one example, transportation is intertwined in the history of Black Americans, beginning with the transport of enslaved Africans to this land hundreds of years ago. After slavery ended, segregation continued to restrict how Black Americans traveled and where they could live. The historic discriminatory land use patterns that affect transportation are discussed in Our Region is Equitable and Inclusive section of Imagine 2050. The Imagine 2050 TPP Evaluation and Performance section of this plan also discusses differences in travel by race, such as the higher use of transit by Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color in the region. The University of Minnesota report Advancing Transportation Equity: Research and Practice further outlines impacts of segregation and the inequities of an auto-dominated system in Minnesota.

Transportation-related disparities

Some of the known transportation-related disparities in the region include:

- The Life and Breath report analysis done in 2022 by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Minnesota Department of Health found that “the highest estimated rates of air pollution-related death and disease are found in neighborhoods with the largest percentage of Black, Indigenous, and people of color, low-income and uninsured residents, and people who live with a disability.”8 Vehicle traffic is a major source of air pollution, and Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color live in higher concentrations in closer proximity to busy roadways.

- Over 30 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act became law, people with disabilities continue to face ongoing challenges with inaccessible infrastructure and programs. While the region has made progress since 2018 in updating local ADA transition plans (discussed in the Pedestrian Investment Plan), significant work remains to transition the transportation system and public right-of-way to meeting the minimums required by the ADA.

- Black and American Indian people are disproportionately killed while walking in the region. 14% of pedestrians killed between 2016 and 2019 were Black, compared to being only 9.6% of the region’s population. 2.3% of pedestrians killed were American Indian, compared to being only 0.48% of the region’s population.9

- Historical impacts from highways such as I-94, I-35W, and Olson Highway are well documented by other local stakeholders. In addition, arterials act as barriers within communities.

- As mentioned above, the University of Minnesota report Advancing Transportation Equity: Research and Practice identifies structural inequities that affect transportation equity, such as the spatial segregation and related mismatch between housing locations and job locations, as well as an auto-dependent system, leading to disconnection and harms for some communities.

Engagement with communities

Inequitable outcomes stem from processes that have historically excluded people, devalued their needs, and denied them power in decision-making processes that affect them. While engagement alone is not equity, working with people in the community who are most affected is central to making processes and outcomes more equitable. The Our Region is Equitable and Inclusive section of Imagine 2050 includes more discussion about community-centered engagement.

Changing processes to be more equitable includes increasing the transparency of decision-making processes and who makes decisions, changing who leads the engagement, and changing who is centered in the work. Engagement work needs to be intentional and meet people where they are with communication that is approachable and understandable. Surveys and public comment periods may not be the best methods to hear from historically underrepresented groups. Those who lead the engagement ideally should be representative of the population they wish to reach.

Incentives for community members

Community members contribute their lived expertise to transportation-related engagement efforts, yet the status quo has been that they are asked to volunteer their time while agency or consultant staff are paid for their involvement. This practice has been changing. The U.S. Department of Transportation publication Promising Practices for Meaningful Public Involvement in Transportation Decision-Making identifies providing financial incentives or reimbursements as one example for building more representative engagement into transportation planning processes. This could be scaled to the level of involvement and range from gift cards for survey or focus group participation to stipends for more ongoing contributions. The eligibility of these costs for federal funds can vary and should be verified before implementing any of these types of activities.

While some agency regulations or practices or state laws may need to change to support broad implementation of this practice across the region for both ongoing advisory groups and project-specific engagement, community members have indicated it is an important and needed evolution of practice.

Recent work by the Met Council

In the Equity Evaluation of Regional Transportation Investment Processes study, the Met Council in partnership with its community-based Equity Policy Group (EPG), developed a framework and tool for evaluating equity within transportation project initiation, funding, planning, and development processes. The framework and tool are being piloted on selected investment processes and following its finalization, the Council will offer regional training sessions for technical staff and community members on evaluating processes and implementing changes through using the Transportation Equity Evaluation Framework and Tool.

The Met Council study on Transportation Needs in Daily Life, completed in 2024, emphasizes understanding transportation challenges faced by vulnerable groups such as the unhoused, people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and older adults, while also addressing impacts and injustices experienced by Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color.

Supporting work by partners

MnDOT’s Advancing Transportation Equity Initiative

MnDOT’s Statewide Multimodal Transportation Plan (2022) includes a commitment to healthy equitable communities and improving equitable outcomes. Key themes through the plan are as follows:

- Eliminate burdens and reduce structural inequities for disproportionately impacted groups.

- Reduce transportation and housing costs for the most burdened.

- Support a diverse workforce through transportation.

- Includes analysis on transportation equity, environmental justice, and Title VI.

In addition to supporting the equity elements of the Statewide Multimodal Transportation Plan, the agency’s Advancing Transportation Equity initiative has conducted recent research on equity:

- Centering the Margins: The Transportation Experience of Underserved Communities (2023)

- Advancing Equity in Accessibility and Travel Experiences: The Role of Gender and Identity (2023)

- Equity in Performance Measurement (2022)

- Advancing Transportation Equity: Research and Practice (2019)

City of Minneapolis Racial Equity Framework for Transportation

The city’s Transportation Action Plan called for the creation of a racial equity framework for use in a transportation context. This was supported by other city work, like the city’s Strategic Racial Equity Action Plan, and other city plans.

City of Saint Paul Rondo Inheritance Fund

The city’s Inheritance Fund program provides downpayment assistance or homeowner rehabilitation funds for low-income residents from the Rondo neighborhood to help build wealth through homeownership in the city for direct descendants of people who owned property that was taken for the construction of I-94.

Human Toll: A Public History of 35W

This community collaboration with researchers at the University of Minnesota, the Hennepin History Museum, and the Sabathani Community Center collected oral histories on the impacts I-35W had on people living in south Minneapolis along the corridor.

ReConnect Rondo

This Saint Paul nonprofit organization has been working since 2016 with the community and government agencies on restorative investments for the Rondo neighborhood including a land bridge over I-94 and cultural district.

Our communities are healthy and safe

Transportation safety is part of public health. Traffic crashes have direct impacts when they result in death or serious injuries. Beyond those effects, people feeling safe and comfortable while traveling can improve mental health and social connection. As such, transportation can be considered a key social determinant of health. Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors – including economic stability, education, health care access and quality, social and community context (including discrimination), affordable and stable housing, and neighborhood and built environments – that influence health outcomes. Transportation uniquely crosses over all these areas since it offers access to these important needs.

Elevating health and safety as a regional goal comes at a time when life expectancy in the U.S. has decreased compared to the early 2000s and lags behind other countries,10 and fatalities and serious injuries from traffic crashes have increased since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Coordinating with partners across areas such as land use, housing, and other services is crucial for improving how transportation can support public health and safety.

Objectives

- People do not die or face life-changing injuries when using any form of transportation.

- People feel safer, more comfortable, and more welcome when using any form of transportation.

- We mitigate and avoid harms to people caused by nearby transportation infrastructure and use (for example, air quality, noise, light).

- People are better connected to community and cultural resources that support their physical, emotional, and mental well-being.

- People can increase physical activity with more opportunities to walk, roll, or bike.

Performance measurement

Performance measures help evaluate how well the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan is addressing the region’s goals and objectives, as defined in this plan and Imagine 2050. Transportation safety is a measure which is required to be tracked by the federal government, while public health measures are tracked regionally for the purposes of this plan. The measures used to track performance for safety and public health in this plan are: fatalities and serious injury rate on roadways; transit safety performance; travel share by mode; and air pollutant emission levels. More on these measures can be found in the Imagine 2050 TPP Evaluation and Performance section.

Since 2020, fatalities and injuries along the region’s transportation system have been increasing. Policies will need to reverse this trend to achieve the objective that people do not die or experience life-changing injuries when using the transportation system.

The Met Council forecasts that regional air pollutant levels will significantly decrease between 2025 and 2050, largely due to increased fuel efficiency and cleaner burning combustion engines over the next 30 years. The Met Council also projects that a combination of improvements to the transit system and demographic changes will create some shifts from automobile travel to transit usage and more active forms of transportation such as biking and walking.

Policies

The Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan sets six policies related to safety and public health. These policies and their supporting actions are detailed in Policies and Actions.

Policy 9. Plan for and invest in transportation facilities that complement existing and planned land use and are dignified and comfortable for all users.

Policy 10. Work to eliminate fatalities and serious injuries from traffic crashes on the transportation system by 2050 through implementation of the Safe System Approach.

Policy 11. Emphasize and prioritize the safety of people outside of vehicles in the transportation right-of-way.

Policy 12. Provide safe, secure, and welcoming transit facilities for all users.

Policy 13. Use transportation investments and priorities to reduce negative health impacts influenced by the transportation system.

Policy 14. Incorporate culturally appropriate placekeeping and placemaking into transportation projects, infrastructure, and right-of-way.

Some of the safety-related actions may be further influenced by work done as part of the Regional Safety Action Plan that is scheduled to be completed in mid-2024. This could include connections to high-injury streets identified in the region through crash data analysis and systemic risk factors.

Work program

Health is a new focus area for the Met Council in planning considerations. We have partnered with the University of Minnesota’s Center for Transportation Studies on a series of workshops related to the Imagine 2050 Transportation Policy Plan goals. The aim is to help identify needed future research and planning-related work. Public health is one workshop focus that will identify needs that the Met Council and partners can address.

One challenge with addressing health connections with transportation is more clearly identifying critical destinations that contribute to public health, such as grocery stores, healthcare facilities, parks, and other everyday destinations. The work program includes a project to define, inventory, and map essential destinations to aid local and regional partners to connect populations to these destinations and improve public health outcomes. The work could also include expanding accessibility analysis to include these essential destinations. This work may be done in partnership with other agencies, such as MnDOT.

On safety, Met Council is planning to develop a Safer Connections to Transit program to ensure safe year-round access to transit for people who are walking, rolling, or biking. Additional work program items may emerge from programmatic recommendations that have not yet been completed as part of the Regional Safety Action Plan.

Major topics

Traffic safety

Arriving safely at destinations or home should be an expectation of a reliable, safe transportation system. Yet every year, too many people die or are seriously injured in traffic crashes involving vehicles. Over the 2018-2022 period, an annual average of 152 people died and 786 people were seriously injured while traveling on roadways in the Twin Cities.11 In addition to these immediate impacts, crashes create other potential effects such as medical and other bills or changes in employment.

Minnesota has supported a goal of zero deaths from traffic crashes for a long time with work through the Minnesota Toward Zero Deaths program, which is a partnership between the Minnesota Departments of Transportation, Health, and Public Safety with participation from local agencies. At the national level, the work toward reaching zero deaths from traffic crashes is now being framed in a Safe System Approach, and work to implement this approach is growing in Minnesota and the region.

Safe System Approach

The Safe System Approach, promoted by the U.S. Department of Transportation, is an important shift in safety planning and implementation. It provides a more holistic approach to addressing traffic safety as a system rather than as individual problems or solutions.

Figure 1.3: Safe System Approach principles and elements12

The Safe System Approach reframes how to address traffic safety with core principles and elements that incorporate these areas. The Federal Highway Administration highlights that “the Safe System Approach requires a culture that places safety first and foremost in road system investment decisions.”

Safe System Approach principles

As outlined in Figure 1.3, the Safe System Approach has six principles:

- Death/serious injury is unacceptable. This approach prioritizes crashes that result in death or serious injuries. The goal is to eliminate these impacts, not eliminate every crash.

- Humans make mistakes. We can’t educate and enforce our way to reliably perfect human behavior. The transportation system needs to be designed and operated so that mistakes don’t result in death or serious injury.

- Humans are vulnerable. Whether traveling outside or inside vehicles, people can take only so much physical impact from a crash with a vehicle. The transportation system needs to be centered on these human limits that cannot withstand the dangers a vehicle-dominant system presents.

- Responsibility is shared. Everyone responsible for the transportation system needs to work to prevent crashes that cause death or serious injury. This includes system designers and operators as well as vehicle manufacturers.

- Safety is proactive. Rather than belatedly fixing issues related to fatalities or serious injuries after they happen, a proactive system uses tools to identify risks and take mitigation steps to prevent these from happening.

- Redundancy is critical. Redundancy in the transportation system means that if one thing goes wrong, other elements are in place to provide proactive protection against death and serious injury.

The Federal Highway Administration provides a summary of the shifts from more traditional safety work to using a Safe System Approach, as illustrated in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: Safe System Approach vs. traditional safety practices13

Safe System elements

The Safe System Approach includes five elements in a holistic context.

Safe speeds

As speeds of vehicles increase the likelihood of crashes becoming fatal rises considerably, at 25 MPH, 90% of pedestrians are likely to survive a crash, while at 50 MPH less than 50% are likely to survive. Reducing speeds helps in three important ways:

- Reduces the impact forces in a crash

- Provides additional time for drivers to stop

- Improves visibility

Managing speeds is a key aspect of the Safe System Approach14. Part of managing speed is ensuring that target speeds are appropriate for the roadway type and context. This is a big difference from more traditional approaches that focused more on exceeding speed limits.

Recent developments have helped restrict high-speed driving, including:

- City speed limits. Since 2019, cities can voluntarily set speed limits on city streets based on a safety, engineering, and traffic analysis. The Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul worked jointly to lower their speed limits in 2020, and some other cities in the region have followed, including St. Louis Park. The two cities provided common promotional materials to residents in each city to build awareness of the changes.

- Speed safety cameras. Cameras that can document speeding drivers are considered a proven safety countermeasure by the Federal Highway Administration. In 2024, the Minnesota Legislature authorized the cities of Minneapolis and Mendota Heights to pilot speed safety camera systems and directed MnDOT and the Minnesota Department of Public Safety to pilot these systems in construction work zones.

- Advanced vehicle technology. The National Transportation Safety Board has called for intelligent speed assistance to be implemented in all new vehicles. It also recommends research and guidelines for implementing this technology as an interlock on vehicles for drivers who repeatedly speed. Passive intelligent speed assistance technology alerts speeding drivers, while active forms of it either make it more difficult to exceed speed limits or prevent drivers from exceeding the limit.

Lowering and enforcing speed limits are not the only tools; other changes are needed to roads and the surrounding environment to provide appropriate guidance to drivers.

Figure 5. Depiction of a “20 is plenty” ad poster from cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul15

The design and operation of roadways can help reduce the severity of crashes and influence behavior, especially drivers.16 The Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety, a National University Transportation Center with several university partners including the University of North Carolina and the University of California, notes that road design should consider current and planned land use contexts so that the most likely travelers are safely accommodated.17 The center also cautions against assuming design manuals will automatically help address needed safety treatments since all included practices are not based on evidence of actual safety impacts; it recommends focusing on reducing risks to road users based on vulnerabilities.18

In January 2024, the Federal Highway Administration released its Safe System Roadway Design Hierarchy, which covers infrastructure countermeasures that can effectively reduce deaths and serious injuries from traffic crashes. The report is intended to be a tool to align the countermeasures and strategies used to apply the Safe System Approach of not accepting deaths and serious injuries. The report frames the existing Proven Safety Countermeasures in terms of how each one addresses this design hierarchy.

Safety applies not only to the occupants in vehicles, but also those traveling outside vehicles. Unfortunately, current vehicle safety ratings do not address safety for people outside of the vehicle. The regulation and design of vehicles can be used to reduce the severity and frequency of crashes to improve safety for everyone.

Technology can assist with safety, but it should not be relied on as the only solution, for example, thinking autonomous vehicles will solve safety issues. The Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety cautions against assuming that technology alone will solve the problem. The center encourages focusing on the basic principles, which apply at the local level: “Work with communities to manage travel speeds and reduce the number of vehicles on our roads through changes to built environments, policies, social norms, message framing, and incentives."17

While this element of the approach may feel out of the realm of state and local agencies, there are opportunities at times to comment to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration on vehicle regulations. Using influence as safety stakeholders can be a strategy in addition to focusing on areas where agencies have more control and responsibility over implementation.

The increasing size and weight of vehicles sold in the U.S. have led to concerns about safety impacts, especially for people walking and bicycling.19 Some local communities in the U.S., such as Washington D.C., are considering addressing larger and heavier passenger vehicles, such as increasing taxes on those vehicles. Newer vehicles often have blunter and higher front ends. These impact pedestrians more severely than smaller cars and trucks do because the point of impact is higher on the human body. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety published research in 2023 that showed larger vehicles were 45% more likely to cause death in crashes with pedestrians.20

The Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety notes in their list of the top Safe System implementation pitfalls that all too often, shared responsibility is equated with equal responsibility. Yet the power to change the transportation system is unequal, as is the role in physical impacts in a crash. Drivers and pedestrians and bicyclists do not share equal responsibility since drivers of vehicles cause the impact. Users of the transportation system do not share the same power to change the system that engineers and elected officials may have. Some road users, such as pedestrians and bicyclists, are also operating within a system that has, for a long time, often not been designed to adequately meet their needs. The transportation system needs to focus on reducing impacts to the most vulnerable users in settings where vehicles present dangers.

Emergency first responders are critical for people involved in crashes to ensure they get the medical care they need promptly, and this is more of a challenge in rural areas. This element also encompasses any needed traffic incident management, the forensic analysis done at crash sites, and other work.

Use of Safe System Approach

Regional studies should incorporate the Safe System Approach and understanding in their work, including prioritizing crashes that would result in death or serious injury and addressing all modes. In November 2023, the Federal Highway Administration released a report on the Safe System Approach for the Urban Core that includes checklists for application at the policy, program, and project levels along with case studies.

Integration of public health with Safe System Approach

Incorporating a public health framework in transportation safety could be helpful in addition to using a Safe System Approach. Recent research proposed a Safe System pyramid to better connect public health principles with transportation safety work.21 Five tiers build this pyramid approach, beginning with socioeconomic factors that are addressed by approaches such as better connecting housing with transit, reforming policies to support reducing vehicle miles traveled, and incorporating safety features in commercial vehicle fleets to more broadly affect health of the population. Changes to the built environment and built-in safety measures such as automated speed enforcement and vehicle standards form the middle tiers. The remaining two tiers focus more on individual effort such as following signals and signs and education campaigns; these are less effective at population-wide levels from a public health perspective. This approach recognizes that impacts from vehicle speeds are the primary cause of injury in traffic crashes that need to be prevented for health outcomes.

Figure 1.7: Safe System Approach pyramid

Safety, comfort, and belonging while traveling

Feeling safe, comfortable, and welcome while traveling means a wide range of things to different people – varying widely depending on intersections of race and ethnicity, gender, age, and disability, and other aspects of people’s identities. Facilities beyond traditional transportation infrastructure can be crucial for safety and comfort, especially for people walking, rolling, biking, and riding transit. (Facility design for these modes is discussed more in each modal investment plan.) These facilities include shade, places to sit and rest, public restrooms, drinking fountains, and eyes on the street from people who may be of assistance when needed.

One of the most challenging areas for addressing safety, comfort, and belonging while traveling in the U.S. and the Twin Cities region is disparities across race and ethnicity. As an example, in the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, harassment of and hate crimes against Asian Americans increased dramatically in the U.S. In Saint Paul in 2021, a community group volunteered to patrol the Frogtown neighborhood near light rail stations and provide escorts for Asian American people to and from the light rail to help provide more of a sense of safety for them.22 The fear felt by many Asian Americans during this time and its effects on travel was brought up by participants in the Met Council’s Transportation Needs in Daily Life study. One focus group participant among caretakers in Anoka County said:

“There were a lot of Asian people that were targeted during COVID. My parents were stuck in the house and totally didn’t want to go anywhere. I would have to encourage [my parents] and say we’re going to the park we always go to. There’s not that many people, but my dad is always very alert. He wants to go where people can see us. It’s sad that they felt they couldn’t go and enjoy their walk. That’s where I come in as a caregiver and say ok let’s go, I’m here.”

Analyses of enforcement data show that people of color experience a disproportionately higher likelihood to experience traffic stops on roads or enforcement on transit. At the request of the Minnesota Legislature, the University of Minnesota Law School conducted the 2003 Minnesota Statewide Racial Profiling Study.23 It found that “drivers of color are overrepresented among those stopped; overrepresented among those searched; and underrepresented among those found to have contraband on their person or in their vehicle as a result of being searched.”

Unfortunately, the 2003 report is the most recent analysis available at a statewide or regional level. Minnesota does not require local police departments to collect traffic stop data including race, so there is not a consistent database to use for routine analysis on potential racial disparities across jurisdictions. Current federal funding promotes the development of statewide data collection and programs to reduce racial disparities in traffic stops. In 2021, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law increased funding to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and flexibility for grants under the federal Section 1906 program to prohibit racial profiling and reduce disparate impacts from traffic stops. This federal funding is an opportunity to address the issue across both the region and the state.

While regional or statewide analysis is hampered by the lack of consistent data, analysis has been done of some local agencies individually. In 2015, Metro Transit analyzed its police incident data by race and found disparities in its treatment of people of color. In 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s Office released an investigative report of the Minneapolis Police Department. As part of this report, they reviewed traffic and pedestrian stop data for the City of Minneapolis for potential racial disparities. This analysis found that Black and Native American people were stopped disproportionately to their population. The analysis also found that traffic stops differed by the predominant racial demographics of neighborhoods; mostly white neighborhoods had fewer minor traffic stops when compared to neighborhoods with more people of color.24

In 2021, Ramsey County changed its traffic stop policies and practices to decrease nonpublic-safety traffic stops such as expired tags or minor equipment violations to reduce racial disparities and focus on public safety issues. The county’s analysis found that Black drivers were four times more likely to be stopped than white drivers for these types of violations. After the changes were implemented in some local police departments within the county, the county found that Black drivers experienced a 66% decrease in nonpublic-safety traffic stops, and the changes did not have an effect on crime in the county.25

The Met Council’s Transportation Needs in Daily Life study highlighted disparities in experiences. The study policy recommendations included repairing and eliminating harms and injustices toward Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color. The study noted these groups “face more safety issues while traveling because of historically discriminatory attitudes and policies embedded in society” and in transportation-adjacent areas like policing, regardless of if they are walking, riding transit, biking, or driving.

Experiences while traveling and choices made for traveling can be very different based on gender and sexual orientation. The Met Council’s Transportation Needs in Daily Life study heard from women who shared stories of harassment, abuse, or violence when they traveled. People who are part of the LGBTQ+ community can also experience verbal or physical harassment or violence while traveling. Personal safety and security concerns lead some of them to restrict travel, especially at night. As part of the daily needs study, one focus group participant among Asian youth in Ramsey County said:

“I guess just being a woman and visibly queer makes it much harder to travel on the bus or train. Because you can be subject to lots of harassment. At night you should not be on the train because of creepy people. Particularly this one night on the train I was in the back, against the wall, these two guys got on. The older guy was beating the younger guy up. I looked around for the number to call or text, but I couldn’t see it.”

Men can also have personal security concerns, but they tend to be significantly lower than those experienced by women. MnDOT released a study in 2023, “Advancing Equity in Accessibility and Travel Experiences: The Role of Gender and Identity,” that found that intersectionality is key when considering gender. Other characteristics such as race, age, and family role intersect with gender with different outcomes and needs. The study also found that nonbinary people “have worse subjective well-being outcomes” than either women or men.