Key water sustainability challenges

Table of Contents

Many factors influence the abundance and quality of water in the region. Over the coming years and decades, new stressors and risks will emerge and current challenges will evolve, putting new pressures and limitations on the region’s waters and multifaceted water systems. The Met Council and its partners have identified a few overarching themes that will impact the region’s waters throughout the life of this plan. These include:

- Growth and development patterns and associated land use impacts.

- Adapting to and mitigating climate change.

- Water contamination, pollution prevention and source water protection.

- Addressing inequitable water outcomes that limit access, use, public and ecosystem health, or other benefits of clean and plentiful water.

- Developing an adaptable water sector workforce able to steward water services and systems.

Growth, development, and land use connections

What happens on land (use/development) directly impacts water quantity and quality. Additionally, the number and density of people living and working in the region, as well as the businesses and industries operating in the region, influences how, how much, where, and what water is used. The connection between the built and natural environment must be considered in short- and long-term planning so that the region’s water needs can be met now, while not compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs as they see fit.

The Met Council strives to foster and maintain a growing economy that benefits all who live, work, and recreate in the region. Sustainable and plentiful high-quality surface and groundwater sources provide a firm foundation for future economic growth, livability, and high quality of life. Likewise, a thriving economy must not come at the expense of, and must be in balance with, the needs of the natural environment, where water is sourced from and returned to after use.

The Met Council forecasts future population conditions in the region and sets regional land use policies through community designations, which group cities and townships based on urban or rural character and historical development patterns. Community designations help jurisdictions implement the regional vision by setting expectations for development density and the character of development throughout the region. For example, the Met Council defines maximum residential development densities to help avoid premature development, protect natural systems, and ensure regional service needs can be met until additional regional growth requires accommodation.

The region’s communities have diverse needs and challenges due to many factors, including their varied natural and urbanized landscapes. Water planning in the region must reflect these diverse needs and landscapes so that complex water issues are properly contextualized and addressed. As the region develops and redevelops, approaches that have resulted in current water issues need to be addressed and solutions must account for historical injustices and community character.

The metro region land area is roughly 50% rural and 50% urban/suburban community designations. Understanding and addressing rural water as opposed to urban challenges and protecting rural landscapes is crucial for achieving regional sustainability. Rural areas are critical for natural system protection, groundwater recharge, and agricultural production, but can negatively impact waterbodies and drinking water sources when not properly planned for or managed. In some areas, contamination from agricultural and industrial practices has impacted aquifers and ecosystems in the metro region.

Similarly, excessive appropriation and use of groundwater sources in rural areas for commercial, agricultural, residential, or other purposes can impact groundwater levels and connected surface waters. However, integrated and collaborative planning, best management practices, remediation efforts, and modern approaches like water reuse are all helping to ensure the needs of rural communities and environments are met, and that the rural character of the metro continues to thrive into the future.

Rural communities face significant obstacles in maintaining wastewater services due to limited financial resources and a challenging population distribution. Fewer people and businesses make meeting the costs of water utility services more challenging. Aging infrastructure and underperformance can further exacerbate concerns and cause systems to become noncompliant, posing environmental and public health risks. The Met Council must work with rural partners to balance stewardship of the environment and health of the population with preserving rural and agricultural land uses outside the long-term service area.

Rural water supply systems face similar challenges as rural wastewater services. Additionally, private well owners do not have the same water quality safeguards as those who get their water from a public system. Testing by counties and state agencies has documented growing problems with water quality in private wells, raising concerns about human health and costs for treatment. The Met Council must also work with partners to help rural communities address their source water protection and drinking water challenges.

Addressing urban and suburban water challenges is equally critical to achieve equitable and sustainable water outcomes. Seventy percent of the region’s population lives in an urban or suburban community. Highly developed and developing communities also face unique water planning and management issues connected to their historical and ongoing development. Areas with limited natural landscapes, expansive impervious surfaces, and significant industrial and commercial areas contend with legacy surface water and groundwater pollution, a lack of natural recharge, and the costs of operating and maintaining complex stormwater, water supply, and wastewater systems.

For example, areas with highways and expansive road networks tend to have surface and groundwaters polluted with chloride, a contaminant that disrupts ecosystem function and is extremely difficult and expensive to remove from water. Urban and suburban communities are also home to natural areas that support surface and groundwater, provide habitat and protect biodiversity, are important recreation and community gathering spaces, and provide refuge from and resilience to climate change impacts. As urbanized areas are redeveloped and new suburban areas are developed, the Met Council will work with partners to provide regional wastewater and water planning and management services to protect, restore, and enhance public and ecosystem health.

The connectedness of the region’s water and water systems also means that actions taken in one part of the metro can have lasting impacts in other parts. Land use changes affect water and water service needs. As the region develops, with associated increases in impervious surfaces (buildings, sidewalks, parking lots, etc.), it impacts the ways that water infiltrates and moves through the region. An increase in impervious surface results in a loss of groundwater recharge, which supports the functioning of healthy ecosystems and supplies drinking water to the region. Instead, it runs off, carrying pollution, and discharges into the nearest body of water through stormwater conveyances like storm sewers and constructed ditches. Constructing and installing best management practices and stormwater management technologies can help to direct water flows to mimic natural pathways.

Responding to climate change across water sectors

Climate change poses immediate and future challenges for the natural and built environment. Changes to the region’s climate affect the condition of water, water needs and uses, infrastructure and utility services, and ecosystem services. In turn, the livability, prosperity, and sustainability of the region face additional risks and uncertainty. Public and ecosystem health, economic growth, and community and individual well-being are threatened when climate change negatively impacts water and water services. These impacts are socially and financially costly and intensify existing disparities for vulnerable people and overburdened communities.

The consequences of climate change will not be felt by all residents or communities simultaneously or in the same ways, potentially worsening current disparities around water services and resources. However, these multifaceted challenges create significant opportunities to develop policies and partnerships that address climate change and ensure the water needs of historically marginalized communities are met.

Limiting the most severe climate change impacts necessitates immediate and sustained action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) and to implement resilient climate design and management (adaptation). Achieving the scale of emissions reductions required for carbon neutrality will result in substantial transformations across every community and sector of the economy, bringing both challenges and opportunities.

Likewise, the region must invest in adaptation to new realities brought about by climate change including increased weather variability, intense precipitation events, prolonged droughts and heat waves, extended growing seasons, and warmer air temperatures. These climate realities have already imposed greater risk to and costs of the region’s water and water utility services. They have altered ecosystems and water management and planning approaches. The region can expect the varied effects of changing climate to continue and become more severe in time, but by acknowledging, planning for, and adapting to new and evolving challenges the region can be prepared for and respond effectively, making the benefits of clean and abundant water resilient now and for the future.

Climate resilience occurs when communities and ecosystems are able to adapt to evolving and challenging climate conditions and mitigate and offset emissions, while ensuring the needs of people and the environment are met and able to recover rapidly and efficiently during periods of stress. The region’s water and water services that support public and ecosystem health and a thriving economy are a foundational component of the region’s climate resiliency. Every aspect of water planning, management, and service delivery must consider how climate change is impacting and will continue to impact the work and the lives of those who depend on it.

The region’s water service providers, watersheds, regulators, and users need to adjust practices, behaviors, and develop coordinated approaches that address risks posed by climate change to water and water infrastructure. For instance, about 30% of the groundwater delivered to homes and businesses by water suppliers in the region is used outdoors primarily for lawn and landscape irrigation. During periods of high temperatures and drought these uses tend to increase, when water sources are likely to be stressed, potentially leading to excessive aquifer drawdown, well interference issues, and impacts to surface waters and surrounding ecosystems.

These high-demand periods also result in increased energy usage and additional water treatment, infrastructure, and associated costs to meet demands. However, by investing in and implementing efficient water use and conservation programs and practices, nonessential water use can be lessened or eliminated, with water sources and connected ecosystems becoming more resilient to climate stresses.

The Met Council produced the Climate Action Work Plan to address areas where we can act and reduce climate change impacts within the organization. The plan’s vision is “to reduce our contributions to greenhouse gas emissions in the region and make our services and facilities resilient to the impacts of climate change.” The Water Policy Plan supports the actions and goals of the Climate Action Work Plan. We are committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing service resiliency in our wastewater operations and support services.

Likewise, through our long-term planning responsibilities, our wastewater and water resource planning sections can help the region adapt by providing technical support for communities to prepare, build resiliency, and grow sustainably. Recent updates to the national climate assessment point to ongoing and future impacts and the need for coordinated climate planning to enhance resiliency.2 As Tribal Nations, the state, watersheds, counties, and communities around the region develop and implement climate adaptation and greenhouse gas mitigation plans, the Met Council can play a role in coordinating climate planning for the region to support cross-jurisdictional collaboration and holistic approaches that build regional resiliency.

Water Contamination, Pollution Prevention, and Source Water Protection

Water contamination and its consequences impact public health, ecosystem function, and regional economic competitiveness. Over the past century, federal and state water protection laws significantly reduced the amount of pollution in rivers, lakes, and streams nationwide, especially since the passage of the Clean Water Act. However, the country has not met the ambitious Clean Water Act goal of all waters being “drinkable, swimmable, and fishable.”

The region is challenged by multiple complex water quality issues. These include increased pollutant-loaded runoff, a growing list of water impairments, contaminated drinking water sources, and high costs for water treatment, utility operations, and infrastructure. The severity and type of contamination impacts how Minnesotans use and value the state’s waters. The sources of contamination are both natural and caused by human activities. Uncertainty around emerging contaminants, regulatory changes, and climate change intensifies these issues, and complicates how to address water contamination. Holistic, proactive approaches and sound water policies are needed so that the region’s waters can meet the region’s needs.

It is difficult to put a price on the value of clean water. Beyond the obvious benefit of maintaining life, the additional benefits of improving water quality include increased property values, protection of human health, aesthetic and cultural value, secure utility and ecosystem services, and sustainable water for future growth and development.

However, the costs to address polluted waters are continuing to grow, including the associated expenses for water utilities who treat water so that it is safe to drink and to reuse or return to the environment. These costs increase the financial burden for individuals and businesses and make the delivery of water utility services more challenging. Investing in proactively addressing water pollution before it happens is far less expensive than paying to address it after it occurs. One of the many benefits of integrated and long-term water planning is the ability to identify risks and opportunities and the tradeoffs necessary to ensure clean and plentiful water in the region.

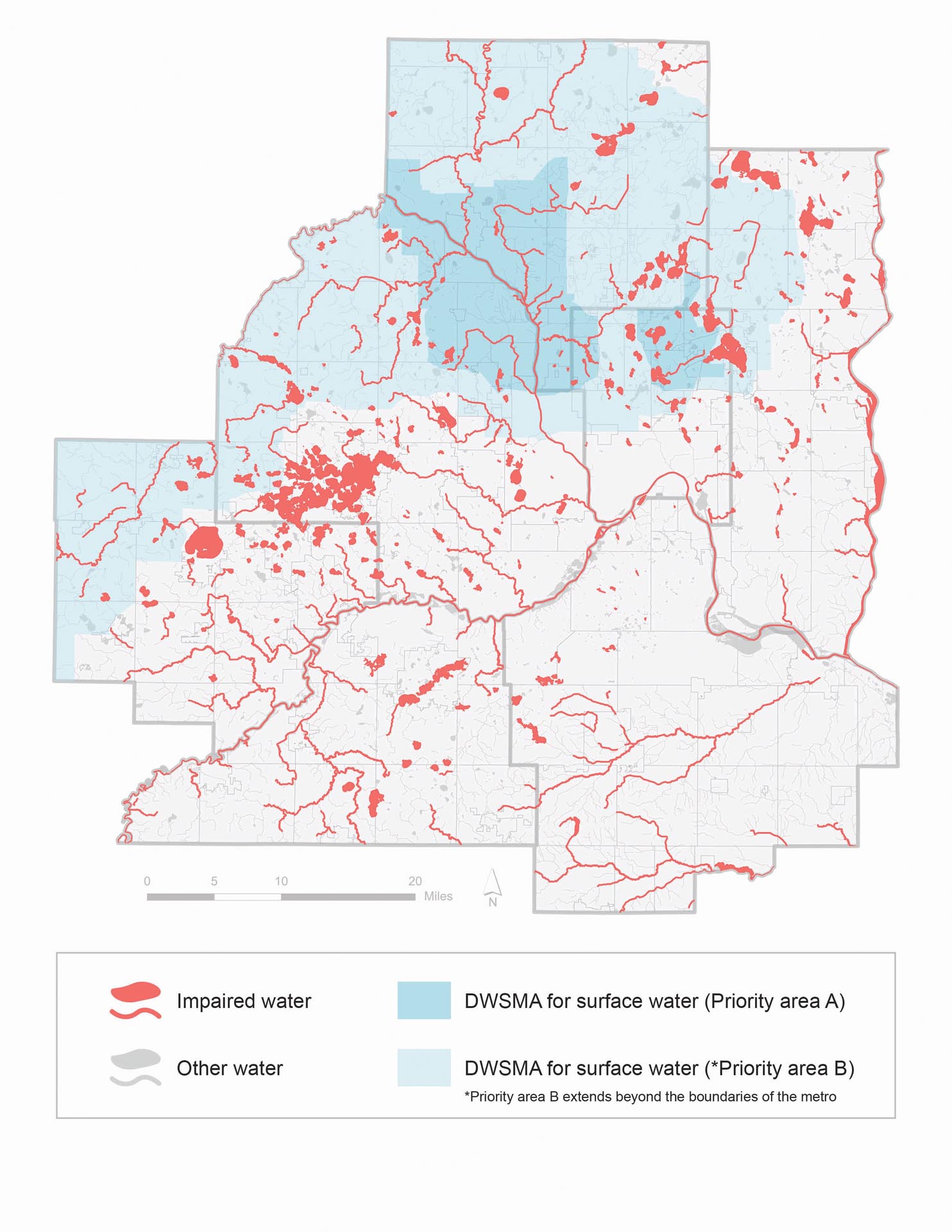

In Minnesota, surface waters that do not meet state water quality standards are tracked on the Minnesota’s Impaired Waters List by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Usually, waterbodies are added due to persistent pollution, increased monitoring, or new, emerging contaminants. Minnesota’s ability to test and monitor across the state for a wide variety of contaminants allows waterbodies that are impaired to be identified and listed, leading to opportunities for increased investment. However, because restoration activities take time to enact and produce measurable outcomes, waterbodies are being listed faster than they are removed. Waterbodies are being removed from the Impaired Waters List, but progress takes time.

Currently, there are 802 water quality impairments in 451 river sections, lakes, or stream reaches in the metro region (Figure 1.4 below), with many waters having more than one impairment.3 Likewise, management and regulation of water usage has advanced significantly in recent decades leading to improved preparedness and resilience, fewer conflicts, improved coordination, and a greater understanding of water sustainability.

The Met Council works with its partners towards the shared goal of safe, sustainable, and sufficient drinking water for the region. Source waters are the rivers, lakes, and aquifers that supply public drinking water systems and private wells. Source water protection is the suite of water quantity and quality actions and policies aimed to protect drinking water from pollution. Public water suppliers and the Minnesota Department of Health are responsible for providing safe drinking water, but they cannot protect drinking water supplies on their own.

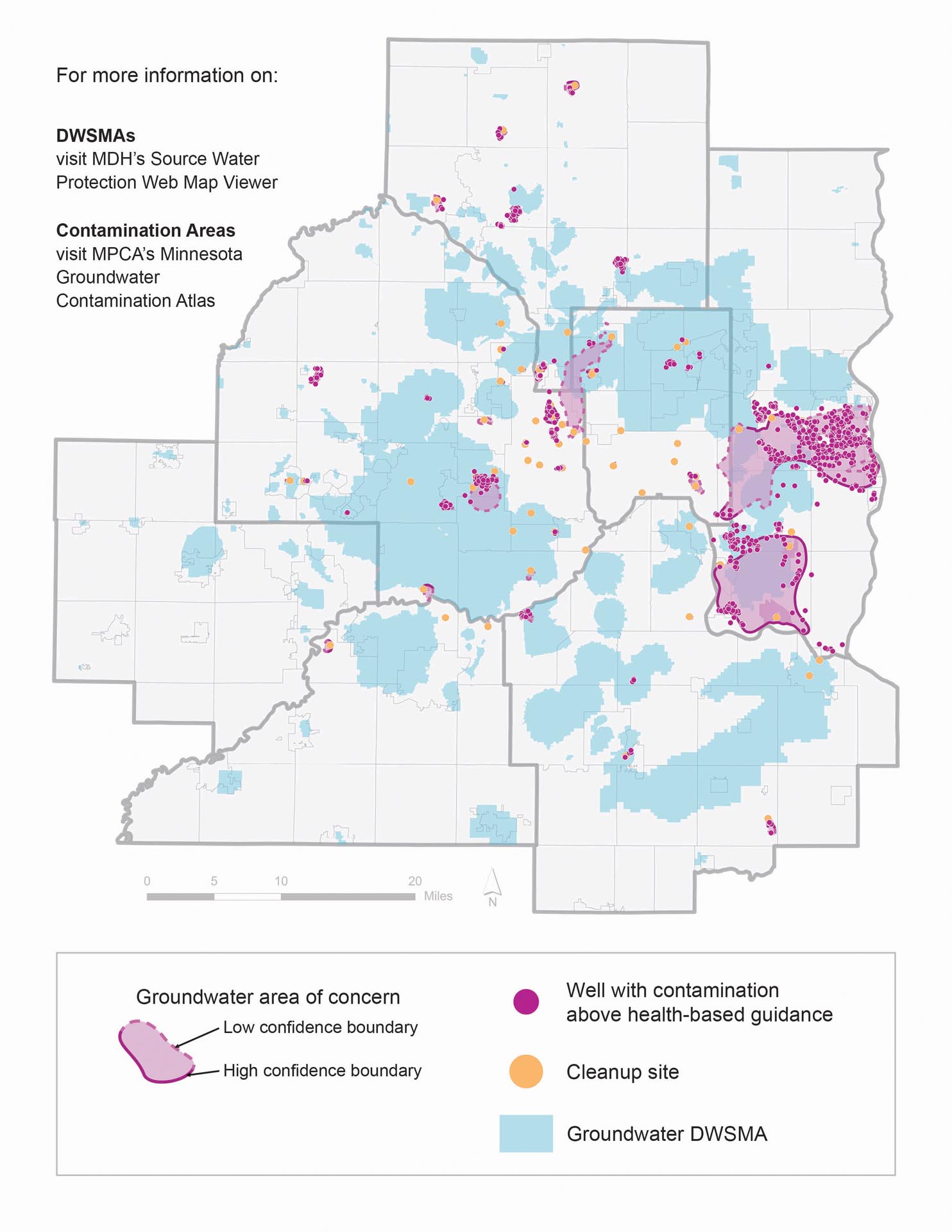

Much of the land within Minnesota Department of Health-designated Drinking Water Supply Management Areas (DWSMAs) is privately owned, and many of these areas extend beyond the jurisdictions where they originate, adding complexity and associated land management challenges for source water protection challenges. Further, some challenges exist due to the nature of underlying geology or where commercial and industrial activities have historically taken place. The Minnesota Department of Health works with public water suppliers, local decision-makers, other state agencies, and partner organizations like the Met Council to plan and implement activities that protect drinking water sources.

About a third of the metro area is currently covered by a Drinking Water Supply Management Area (Figure 1.4 and Figure 1.5), although these areas are expected to change over time as the Minnesota Department of Health updates their delineation methods (particularly for surface water DWSMAs). Around three million people, over half of Minnesota’s population, are currently supplied by water flowing through these areas. In addition, roughly 200,000 people get water from private wells, which do not have surrounding areas mapped for protection. Private well owners are responsible for following the health department’s guidance to protect their supplies; however, they too have limited ability to address contamination risk beyond their properties. All land use decisions, large and small, can impact source waters, making collaboration between communities, agencies, water providers, and private groups necessary to achieve source water protection goals.

Figure 1.4: Surface Water Drinking Water Supply Management Areas and Impaired Waters

Figure 1.5: Contamination areas and groundwater Drinking Water Supply Management Areas

Numerous contaminants can impact water quality in various ways. Table 1.1, below, focuses on major contaminants or groups of contaminants that are of great concern to the region’s waters. Some of these contaminants have been long known (nutrients and chloride) and some are of more recent concern (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). Initial efforts to understand and address the contaminants identified in this section through monitoring, assessment, investigatory taskforces, or technical advisory groups has begun. But further work and innovative approaches are needed to fully remediate the impacts of these contaminants.

Table 1.1: Major contaminants or groups of contaminants that are of regional concern

| Water type | Example contaminants | Concerns |

|

Groundwater |

|

|

| Surface water |

|

|

| Wastewater |

|

|

Contaminants of emerging concern have become a priority for public water suppliers, water resource professionals, and the public. Emerging contaminants are human-made, chemical compounds detected at low levels in water that can have a detrimental impact on public health and aquatic life. Microplastics, pharmaceuticals, and PFAS are all examples of emerging contaminants that are impacting natural waters, water supplies, wastewater, and the regulatory environment. New emerging contaminants are being identified as public health risks, and water professionals are learning more about how chemicals impact human health and the environment. There will always be “unknown unknown” contaminants, and the region needs to be prepared, adaptable, and have the resources it needs to address new challenges quickly and efficiently as they arise.

Equitable water services, planning, and management

The Met Council holds that accessible, affordable, sufficient, and safe water for personal and domestic use is a human right. This right has been identified by the United Nations, recognized in international law, and by some U.S. states and local laws and policies. Likewise, water should be plentiful and clean to support healthy ecosystems and the life that depends on them, including the needs of humans. While some environmental location-based factors influence water quality and availability, the major drivers of water and water service disparities are historic and ongoing social, cultural, economic, and political inequities.

Across the United States, public policymaking has a long history of disproportionately favoring certain communities at the expense of others. Resources have been directed away from low-income, immigrant, and communities of color and toward affluent, predominantly white areas. Both financial and legal practices such as redlining and racial covenants limited the social and economic mobility of and opportunities for Black, Indigenous and persons of color (BIPOC). Discriminatory zoning laws and urban renewal policies have bolstered white affluence as families moved to suburban and higher-income neighborhoods while further constricting BIPOC families’ housing options.

Planners at all levels of government have exacerbated inequality by continually identifying low-income neighborhoods for the siting of industrial development, creating environments where pollution has been concentrated and public health has suffered. These practices have impacted water quality, availability, and accessibility, contributing to a lack of trust in water services. Communities that are presently overburdened are disproportionately impacted when new issues arise, including the effects that climate change has on water and water services.

The Met Council and other partner organizations in Minnesota are members of the U.S. Water Alliance, a national, water-focused nonprofit, which has identified key issues to address to achieve equitable water outcomes. Issue areas to address fall under three foundational pillars of water equity for water utilities:

- Ensure all people have access to clean, safe, and affordable water service

- Maximize the community and economic benefits of water investments

- Foster community resilience in the face of a changing climate

In Imagine 2050, equity is identified and incorporated as a key value and objective of current and future planning and policymaking. The Met Council has developed an equity framework that guides us and the region towards an equitable future through the development of policies and actions that are community-centered, reparative, and contextualized to ensure solutions are addressing systemic inequity. We have also developed an environmental justice framework that is grounded within the equity framework. Environmental justice is the right for all residents to live in a clean, safe environment that contributes to a healthy quality of life. The environmental justice framework prioritizes:

- People-centered, data-driven decision making (contextualized)

- Engagement with overburdened communities (community-centered)

- Solutions that benefit communities beyond harm mitigation (reparative)

The work of the Environmental Services division plays a critical role in achieving environmental justice and equitable outcomes for the people of the region by listening to community concerns, centering environmental justice in our own planning and operations, and providing resources and guidance to local organizations.

Environmental justice and equity concerns regarding water include:

- Access to, and impairment of, waters for fishing and recreation.

- Access to, and affordability of, clean drinking water.

- Climate preparedness and resiliency of water infrastructure and utility services and associated costs for overburdened residents and communities.

- Pollution impacts on nearby communities.

- Affordability of wastewater treatment fees.

- Affordability of treatment technologies to address private drinking water contamination.

Water sector workforce development

Nationally, and in our region, the water sector faces a critical shortage of skilled workers across various disciplines, including engineering, management, and technical operations. This shortage threatens the sustainability and efficiency of water resource management, jeopardizing public health, environmental conservation, and economic development. The challenge lies in developing a robust and diverse workforce equipped with the necessary expertise, innovation, and leadership to address emerging challenges such as aging infrastructure, climate change impacts, and evolving regulatory requirements.

Demand for skilled professionals in the water sector continues to grow due to a smaller pipeline of workers, evolving technologies, aging infrastructure, and emerging environmental challenges. Furthermore, the lack of diversity in the workforce poses a significant threat to innovation, creativity, and effective problem-solving.

Environmental Services was fortunate for decades to have a strong talent pipeline. However, as in the water workforce nationally, the water workforce in Minnesota is homogenous and aging. On the national level, nearly 85% of the water workforce is male, more than two-thirds of the workforce is white, and the average age of most water employees is above the national average for all workers. Unfortunately, our workforce is even less racially diverse than the national figure and the overall Twin Cities regional population.

Furthermore, at this moment, 20% of the Met Council’s water workforce is eligible for retirement. People of color are leaving the organization at a faster rate than their white peers. The percentage of women employed in the organization has trended downward for the past four years, currently sitting at 21% (near its lowest point since visible in data made available).4 Declining enrollment in the past decade and the closing of one of the local wastewater treatment education programs, along with fewer people going into labor roles, has led to a smaller pool of applicants.

The water sector faces challenges in fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion within its workforce and workplaces. Despite efforts to promote equal opportunity and representation, disparities persist in recruitment, retention, and advancement opportunities across various demographics. Women, racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with disabilities, and other historically marginalized groups remain underrepresented in key roles within the water industry, hindering the sector's ability to harness the full potential of a diverse workforce.

Inequitable access to education, training, and career advancement pathways further aggravates these disparities, perpetuating systemic barriers to entry and progression for underrepresented groups. Additionally, cultural biases, discriminatory practices, and lack of inclusive policies in some water organizations contribute to an unwelcoming work environment for diverse employees, resulting in high turnover rates and diminished productivity.

A comprehensive policy framework that addresses the root causes of inequity and promotes diversity, equity, and inclusion throughout the water workforce should encompass:

- Targeted recruitment strategies

- Inclusive hiring practices

- Equitable access to training and development opportunities

- Culturally competent leadership

- Supportive workplace policies that foster a culture of belonging for all employees

By proactively addressing these challenges, the water sector can build a more resilient, innovative, and sustainable workforce and future talent pipeline that reflects the diversity of the communities it serves and ensures equitable access to clean and safe water for all.

2 U.S. Global Change Research Program. (2023). Fifth national climate assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023

3 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. (2024). Minnesota’s 2024 impaired waters list. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/minnesotas-impaired-waters-list

4 Metropolitan Council internal “HR Workforce Dashboard.”

An official website of the

An official website of the