Regional water context

Water has always held great significance to the people of the region. The name Minnesota comes from the name the Dakota people gave this land, Mni Sóta Maḳoce – meaning “The Land of Mist.”1 From the continental ice sheets that shaped the land forming lakes, rivers, and wetlands nearly 16,000 years ago, to the Indigenous cultures that have flourished living alongside those water features, to the present day’s thriving and diverse communities, water has defined the people and places of our metropolitan region.

Sustaining plentiful and clean water

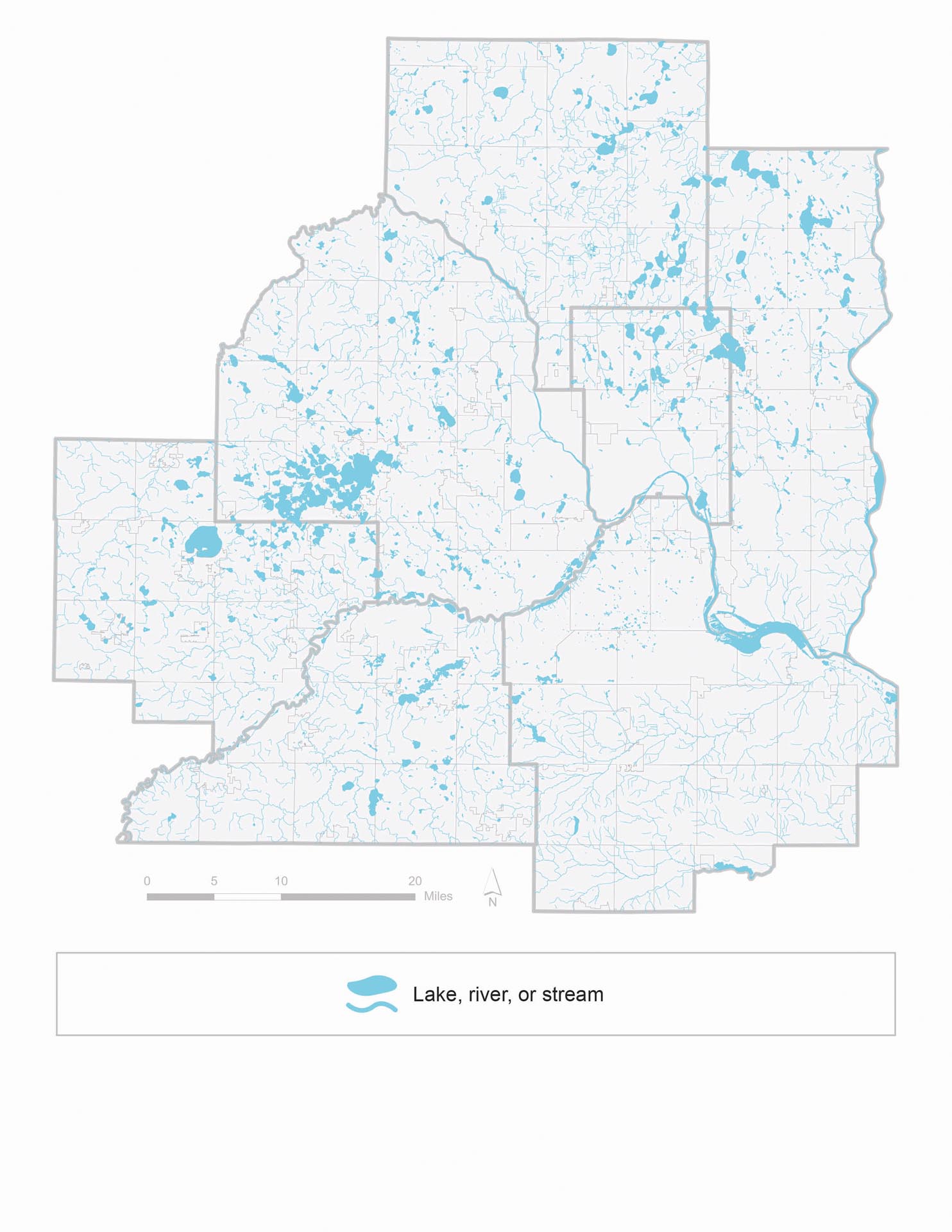

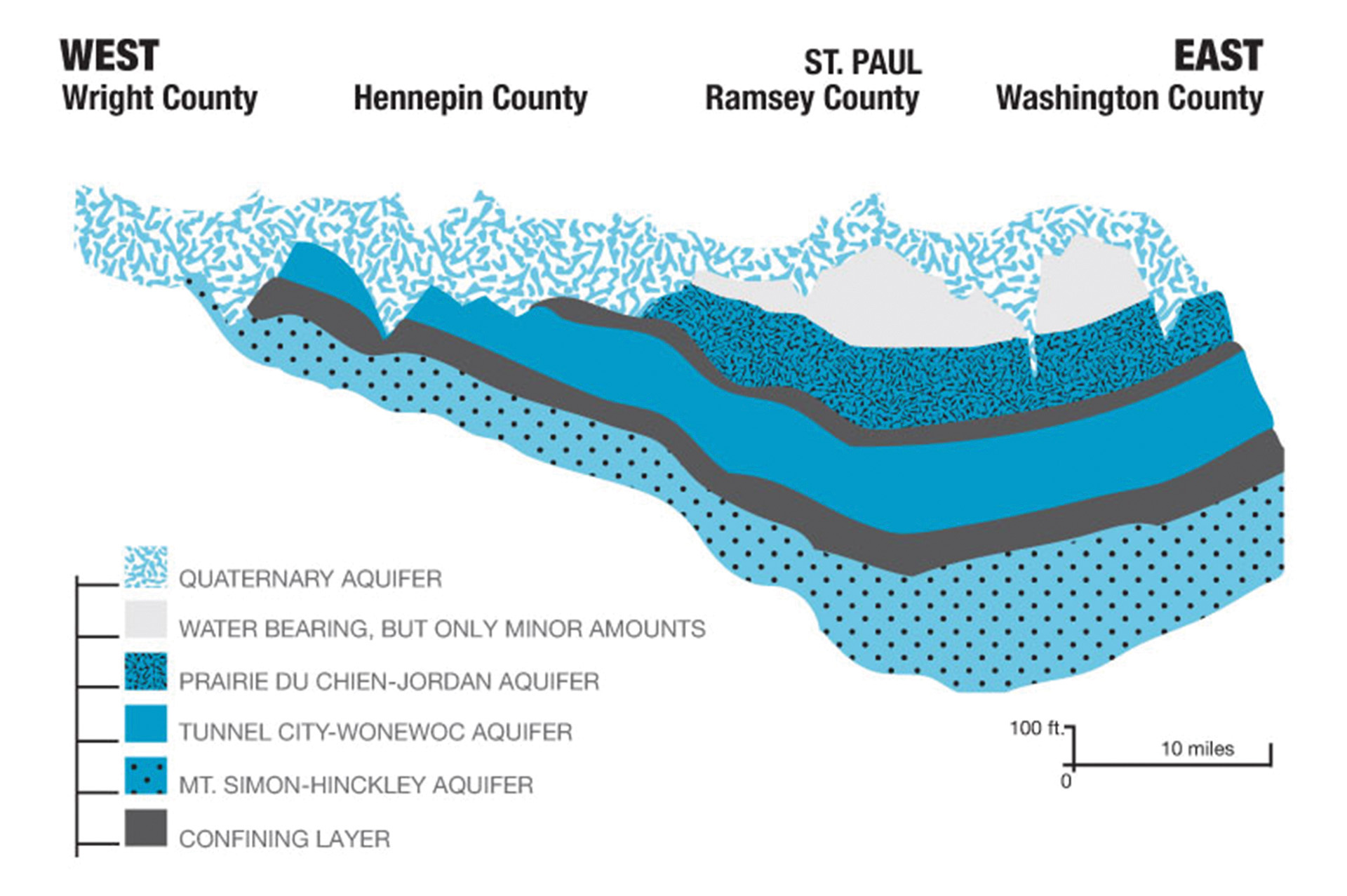

Plentiful, high-quality water is a foundational pillar of public and ecosystem health and thriving economies. The seven-county metro area includes nearly 3,000 square miles of diverse landscapes, from highly developed cities to large rural agricultural areas. Equally diverse are the water needs of the more than 3 million people, over half of Minnesota’s population, who reside here. These landscapes include almost 1,000 lakes, hundreds of miles of rivers and streams, and thousands of acres of wetlands (Figure 1.1). Below ground there are surficial sand, gravel, and major bedrock aquifers that provide nearly 70% of the region’s water supply (Figure 1.2).

Water Resource Recovery Facility

Our wastewater treatment plants do so much more than treat wastewater; they produce clean water, recover nutrients for second uses, and tap renewable energy to reduce fossil fuel use.

Our change in name from wastewater treatment plans to water resource recover facilities reflect that our work is more than only wastewater treatment.

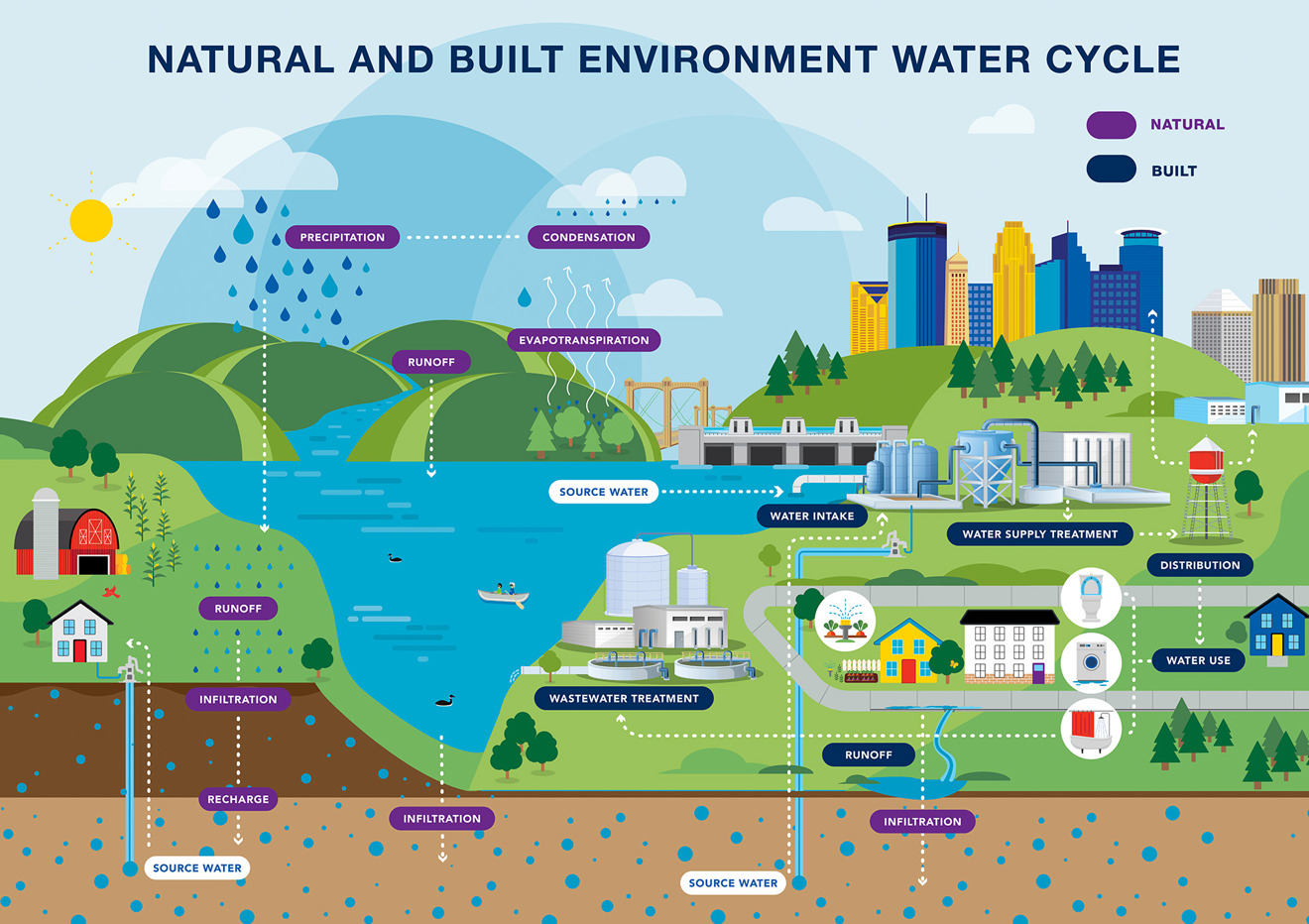

Water is supplied to homes, businesses, and industries by more than 100 municipal community public water supply systems and tens of thousands of private and nonmunicipal public wells. Stormwater is conveyed through thousands of miles of stormwater infrastructure that allows it to safely replenish the water table and groundwater system. Used water is treated by individual subsurface sewage treatment systems, municipal wastewater facilities, private communal wastewater systems, and the regional water resource recovery system, which includes 9 water resource recovery facilities serving 111 communities. The treated water from these facilities is then safely returned to the environment or reused to improve the sustainability of the region’s water sources.

As water moves through this landscape, it provides residents with sustenance, spiritual solace, recreational enjoyment, the ability to transport goods, and the potential for industrial power. This same water also supports biodiversity and natural systems that are resilient and provide a high quality of life.

The region’s water naturally cycles to and through surface water features and an extensive groundwater system. While often regulated and managed separately, groundwater and surface water are an integrated system that works to support ecosystem health and the needs of people. The natural system is continually influenced by the built environment consisting of developed landscapes that include engineered water systems (stormwater conveyance, water supply utilities, subsurface sewage treatment systems, and wastewater systems and utilities). No part of this natural and developed water landscape is without human influence or intervention, and issues or solutions in any part of the system are likely to have connected impacts on the whole.

Community growth and development cannot occur without sustainable water and water services. The region’s waters (ground and surface water) are sustainable when managed to not harm ecosystems, degrade water quality, and to ensure their availability for current and future generations - safeguarding economic, environmental, and social well-being. If stormwater, water supply, and wastewater infrastructure that treats and moves water throughout the region is put at risk, the essential services provided by these engineered water systems cannot be sustainable. Sustaining natural waters and the services that provide clean and plentiful water is essential for public and ecosystem health, and to ensure a high quality of life for present and future generations.

Water sustainability occurs at the confluence of social, economic, and environmental factors. This tells us that issues that create risk and limit benefits cannot be addressed in any one water planning or management sector, and that our planning and management approaches must be holistic and adaptative to allow for new knowledge and ways of thinking to inform decisions. The region cannot achieve and sustain clean and plentiful water if we do not understand environmental conditions or the socioeconomic factors that drive needs and risks.

Figure 1.1: Regional rivers, lakes, and streams

Data source: Minnesota DNR

Figure 1.2: Regionally significant aquifers

Graphic source: Met Council

Figure 1.3: Water movement through the natural and built environment

Graphic source: Met Council

Benefits of regional water planning

Water naturally flows along topographic and geologic boundaries and is defined by its physical and chemical properties and hydrologic conditions (see image above). However, when we define water, we tend to think of the water nearest to us, or that we interact with the most. Rarely do we think of the journey water has taken to get to us or what happens after we interact with it.

It’s also rare that we consider how water moves through our communities and eventually flows out of the region. This movement of water into and out of the region can take as little as a few days, as in the case of stormwater, or as much as several thousand years, in the case of groundwater that’s pumped from deep bedrock aquifers for water supply, treated post-use, and returned to the environment.

All residents, businesses, and communities have a responsibility to protect and conserve water as it moves through the region. We must consider how land and water are used, how the region’s landscapes are developed and redeveloped, and how water needs and challenges vary from place to place. We need to identify and remedy past decisions that have polluted waters, harmed ecosystems, made water and water systems less resilient to climate change impacts, and increased the costs of water services and management. This stewardship requires integrated holistic approaches and collaborative planning between communities, watersheds, and water regulators.

The Met Council is the regional wastewater service provider, we plan for development and integrated water planning, and we make regional policy. We are well situated to help the region find solutions to complex challenges and meet the water needs of current and future generations. We partner with communities to address the long-term sustainability of water resources and water utilities by:

- Providing integrated water planning and sustainable wastewater management to the region.

- Facilitating collaborative planning activities throughout the region.

- Building partnerships with communities, local governments, watersheds, technical experts, and state and federal agencies, inside and outside of the region.

- Supporting sound local and regional decision making with data, information, tools, and grants.

- Monitoring the quality and quantity of the region’s water resources.

1 This translation was provided by the Met Council’s American Indian Advisory Council.

An official website of the

An official website of the