Water Supply Plan

Table of Contents

Providing guidance for regional and local community water supply planning

Focusing funding for regional and local water supply work

Connecting water supply planning to other regional plans

Challenges for the region’s water supply

Opportunities for regional water supply planning

High-level roles for water supply planning and implementation

Regional water supply action plan

Approaches reflect how water supply planning conditions vary across the region

Definition of success for water supply planning in the metro

Actions to support successful water supply planning

Regional indicators and performance measures

Subregional water supply action plans

Process to develop subregional action plan content

Purpose and use of subregional action plans

Central Metro subregional water supply action plan

East Metro subregional water supply action plan

Northeast Metro subregional water supply action plan

Northwest Metro subregional water supply action plan

Southeast Metro subregional water supply action plan

Southwest Metro subregional water supply action plan

West Metro subregional water supply action plan

Providing guidance for regional and local community water supply planning

The Twin Cities seven-county metro region is home to three million people, over half of Minnesota’s population. Securing residents’ safe and plentiful water – while protecting the region’s diverse water resources – requires coordinated, interdisciplinary, and ongoing effort.

The seven-county region is relatively water-rich. However, communities face a range of challenges as they work to meet current and future water demand. The region’s population continues to grow. Groundwater pumping is increasing. Land use is changing. Naturally occurring and manmade pollutants impact water supplies. And variable weather like floods and droughts, as well as longer-term climate change, affect water supplies. Learn more in the Water Supply Planning Atlas.

The development of this plan is not motivated by widespread water shortages or crises. Rather, this plan is a response to the recognized benefits of coordinated action to support the water needs of current and future populations without adverse impact to natural and economic resources.

Bringing together the many different and changing facets of water supply into a regional picture is outside the scope of any one community. Yet it is necessary to adequately plan for the region’s growth and economic development, and it is an appropriate role for the Metropolitan Council.

We recognize the responsibility and authority of local water suppliers to provide water. However, a regional perspective is also important, because the effects of local water supply decisions do not stop at community boundaries. Communities often share the same or interconnected water supply sources – aquifers cross many political lines, for example – and the cumulative impact of decisions made by individual communities can be significant.

The plan provides guidance for local water supply systems and future regional investments; emphasizes conservation, interjurisdictional cooperation, and long-term sustainability; and addresses reliability, security, and cost-effectiveness of the metropolitan area water supply system and its local and subregional components.

The Metropolitan Area Water Supply Plan provides a framework for sustainable long-term water supply planning at the regional and local level in a way that:

- Supports local control and responsibility for water supply systems

- Is developed in cooperation and consultation with local, regional, and state partners

- Highlights the benefits of integrated planning for stormwater, wastewater, and water supply

The collaborative process to develop and implement this plan supports communities to take the most proactive, cost-effective approach to long-term planning and water-supply permitting to ensure plentiful, safe, and affordable water for future generations.

Focusing funding for regional and local water supply work

Since 2010, the primary source of funding for the Met Council’s regional water supply planning and support for local implementation has been Minnesota’s Clean Water Fund, which is currently available until 2034. This funding supports the following two Met Council programs that increase communities’ implementation of projects to help achieve sustainable water supplies:

1) Water demand reduction grant program: Provides grants for communities to implement water demand reduction measures to ensure the reliability and protection of drinking water supplies.

2) Metropolitan area water supply sustainability support: Implementing projects that address emerging drinking water supply threats, provide cost-effective regional solutions, leverage inter-jurisdictional coordination, support local implementation of water supply reliability projects, and prevent degradation of groundwater.

The following water supply-related planning activities are historically funded through limited Met Council funds:

- Review of local water supply plans, comprehensive plan updates and amendments, wellhead protection plans, or other environmental review documents

- Technical support for communities in developing local plans

- Coordination and support for the Metro Area Water Supply Advisory Committee and its Technical Advisory Committee or subregional water supply work groups

- Coordination and development of the Metro Area Water Supply Plan

This Metro Area Water Supply Plan lays out stakeholder-identified needs for continued financial support through resources such as, but not limited to, Minnesota’s Clean Water Fund (Table 3.2 and subregional water supply action plans).

Additional funding sources will be pursued by Met Council, local governmental units, and partners in order to implement water supply planning activities contained in this plan.

Connecting water supply planning to other regional plans

The metro area water supply plan is informed by and supports the 2050 regional development guide, Imagine 2050, and is part of the 2050 Water Policy Plan. It more specifically provides water supply-related considerations for developing regional, subregional, and local plans as well as supporting programs.

Regional water supply context

General water supply setting

Effective water supply planning looks at the entire water cycle. Understanding the region’s "waterscape" helps identify upstream issues and opportunities, downstream impacts, and relationships among water stakeholders and agencies. Keeping these elements in mind is important when discussing water supply policy and planning. Learn more in the Water Supply Planning Atlas.

Climate and weather

The region’s water ultimately comes from precipitation that falls locally and in upstream watersheds. Precipitation quickly fills surface water sources, while it takes decades to centuries to reach deep aquifers.

Landscape (source areas)

The amount and quality of water that we can pump from surface and groundwater sources depend on the environment that precipitation travels through. In this region, urban, suburban, and rural areas each have different water sources, soils, geology, and land use patterns.

Water supply sources

We pump water from four extensive and interconnected underground layers of rock, gravel and sand (aquifers) and from the Mississippi River. These sources supply large volumes of water for commercial, industrial, and residential uses. We also have growing opportunities to use treated stormwater and reclaimed wastewater, which could provide water for nonpotable uses such as cooling or irrigation, and potentially even for drinkable use in the future.

Water supply infrastructure

Over 100 municipal community public water systems provide most of the region's water. These systems include surface water intakes, wells, treatment facilities, storage, and distribution pipes that provide safe water. Additionally, over 60,000 non-municipal wells serve parts or all of many communities. Privately owned wells and subsurface sewage treatment systems, which are maintained by their owners, must meet well codes and local regulations.

Water users/customers

Clean water is essential for everyone. People and businesses in our communities use large amounts of water for commercial, industrial, and residential purposes. As customers, they fund the infrastructure needed to supply this water and also pay for the disposal of used water.

Wastewater and water resource recovery infrastructure

Over 10,000 miles of local infrastructure collects wastewater and send it to a regional system including nine water resource recovery facilities. Homes and businesses may use private subsurface sewage treatment systems or connect to a community system. Regional treatment cleans water to meet state and federal standards.

Discharge to environment

Stormwater and treated wastewater are released back into the environment, sometimes cleaner than the water it is discharged to. This water then flows downstream to other users and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico.

Challenges for the region’s water supply

Everything that happens on land impacts water, and all water is connected. Recognizing the upstream and downstream connections among water supply hazards helps to identify the biggest risks and focus monitoring and mitigation measures. Learn more in the Water Supply Planning Atlas.

Climate and weather

Minnesota is known for its extreme seasonal differences, and precipitation varies significantly from year to year. Flooding, drought, and recharge changes are current challenges, and climate change serves as a risk multiplier for disaster preparedness.

Landscape (source areas)

Land use affects the quality and quantity of our water supply through things like paved surfaces, agriculture, industry, snow and ice removal, and stormwater management. Various contaminants from different sources can pollute water, and the landscape's sensitivity varies. Managing the water supply impacts of development is a key challenge that local plans must address.

Water supply sources

The region’s water supply sources are interconnected and have various limitations and costs. Not all sources are equally available or productive, and some are not available year-round. Recharge rates vary, and there may be nearby competing demands where high-volume water use in one location affects another. Sources also differ in their risk of contamination and may have existing pollution. Their use may be impacted by regulated withdrawal limits and treatment requirements to protect public and environmental health.

Water supply infrastructure

Both municipal and non-municipal water suppliers face challenges in meeting supply needs, maintaining public health, and keeping water affordable. These challenges include aging infrastructure, cybersecurity risks, changing water demand due to growth and development, decreased revenue, contamination, new and stricter regulations, and a changing workforce. Private well and subsurface sewage treatment system owners also face issues; many older systems no longer meet updated codes and ordinances.

Water users/customers

By 2050, about 650,000 more people and 500,000 new jobs will be in the region compared to 2020. If we keep using water as we do now, this growth will raise water demand, stressing current infrastructure and sources. Planners must carefully weigh the impact of new demands, especially from businesses and new high-volume users, to understand local costs and benefits. Building trust with water customers and communities is crucial for ensuring enough resources to provide and safeguard water supplies.

Wastewater and water resource recovery infrastructure

Utilities face challenges to provide affordable, safe, and trusted wastewater treatment. The decisions customers make about water use and disposal affect the local and regional wastewater systems, impacting investments in capacity, treatment, and maintenance. Aging infrastructure, decreased revenue, contamination, and changing regulations and workforce exacerbate the challenges.

Discharge to environment

When the water quality standards for water downstream change, it can affect the systems that manage wastewater and water supply upstream.

Opportunities for regional water supply planning

Successful water supply planning includes supporting opportunities throughout the region’s ‘waterscape’ to implement practices to monitor, protect, and restore natural and built water resources. Learn more in the Water Supply Planning Atlas.

Climate and weather

Paying more attention to and putting more resources into reducing energy use, improving stormwater management, and supporting disaster preparedness and emergency response planning can also help to better manage water demand and protect our water sources and public health.

Landscape (source areas)

New development and redevelopment are opportunities to use water more efficiently and protect both where our water comes from and infrastructure downstream. For example, using better indoor appliances and fixtures and drought-resistant landscaping can help limit indoor and outdoor water use, and keep usage balanced through the year. Choices about land use also matter in making sure we use water sustainably and prevent contamination in the long term. It's also important to have good guidance on how many people will be living here in the future, so our plans for growth fit well.

Water supply sources

Long-term planners now have better information about the size and vulnerability of source water areas, thanks to improved monitoring, mapping, and modeling. This helps them make smarter decisions when planning and investing in water resources. There's also more interest and investment in exploring different water source options, such as reusing water, teaming up with nearby systems, and expanding the use of surface waters.

Water supply infrastructure

With more focus on and resources for water supply asset management planning, there is a chance to promote integrated water management within and among communities. Another opportunity lies in educating and offering incentives for monitoring and maintenance to private well and subsurface sewage treatment system owners. This not only safeguards public health but also empowers individuals to make informed decisions.

Water users/customers

Ongoing education and engagement, supported by state and local controls and incentives, provide an opportunity to encourage water-efficient practices (indoor and outdoor) and build support for sustainable investments in water supply and source water protection.

Wastewater and water resource recovery infrastructure

We have opportunities to maximize the benefits of our current local and regional infrastructure investments. For instance, by reducing inflow and infiltration, we can enhance capacity. Similarly, by reusing reclaimed water, we can expand water supply availability.

Discharge to environment

Examining the entire water cycle to meet downstream discharge standards presents an opportunity to pinpoint the most cost-effective areas for changes that benefit the entire region. This approach can also enhance natural systems, stabilize temperature fluctuations during droughts, and increase supply for downstream users.

High-level roles for water supply planning and implementation

Everyone – agencies, business, individuals – has a responsibility for ensuring sustainable water supply planning. Collaborative actions are needed at the individual level, the local government level, the regional level, and the state and federal levels. Some examples of key roles are summarized below.

Climate and weather

Local governments take a wide range of local actions to mitigate climate and climate change risks in their communities. Met Council implements its internal Climate Action Work Plan and supports local planning and implementation. The State of Minnesota provides statewide climate adaptation and mitigation action, critical climate research, convenes flood and drought response teams, and takes many other actions.

Landscape

Local governments have land use authority along with some counties. Watersheds, counties, and Met Council have roles guiding land use. As regulators, state water agencies help incentivize public and private sectors to improve land use best practices.

Water supply sources

Local governments are tasked with identifying sustainable water sources, applying for water appropriation permits, and collaborating with neighboring jurisdictions. State water agencies serve as regulators, collecting and analyzing water data, assessing supply risks, setting standards and rules, developing best practices, approving local plans and permits, administering funding programs, and offering technical assistance and training. Met Council evaluates regional water resources and offers planning, guidance, and resources to safeguard them.

Water supply infrastructure

Both public water supply systems and owners of private wells are responsible for developing, maintaining, and using wells for domestic and commercial needs. Local governments supply water to customers in compliance with Safe Drinking Water Act standards. They set rates, maintain infrastructure, monitor water quality and quantity, establish emergency procedures, enforce demand reduction measures, and plan for land use, water supply, and capital improvements. State agencies license contractors and other professions affecting drinking water, oversee water well construction and sealing, approve local plans and permits, administer funding programs, and offer technical assistance and training.

Water users/customers

Residents, property and business owners have an important role to play as ratepayers and choosing best practices for their properties and businesses. They can also have influence with their city councils and township boards. State, regional, and local water supply planners can communicate information and tools to support them.

Wastewater and water resource recovery infrastructure

Local governments plan for local land use, water supply, wastewater (municipal and subsurface sewage treatments systems) and capital improvements. Met Council does the same at the regional scale, including operation of the state’s largest regional wastewater treatment system.

Discharge to environment

Met Council monitors receiving waters. State water agencies as regulators collect and analyze water information, assess water supply risks (quantity and quality); and develop standards and rules.

Regional water supply action plan

Approaches reflect how water supply planning conditions vary across the region

Water supply conditions vary widely across the region and among communities. Each city has different sources, treatment methods, and water use patterns. For example, some areas have high commercial and industrial demand, while others mainly use water for residential purposes. What works for one community may not work for others, so regional water supply planning must consider this when setting goals and tracking progress. As communities plan for future water needs, their approaches will be influenced by their unique water supply situations. Learn more in the Water Supply Planning Atlas.

Locations of different water sources

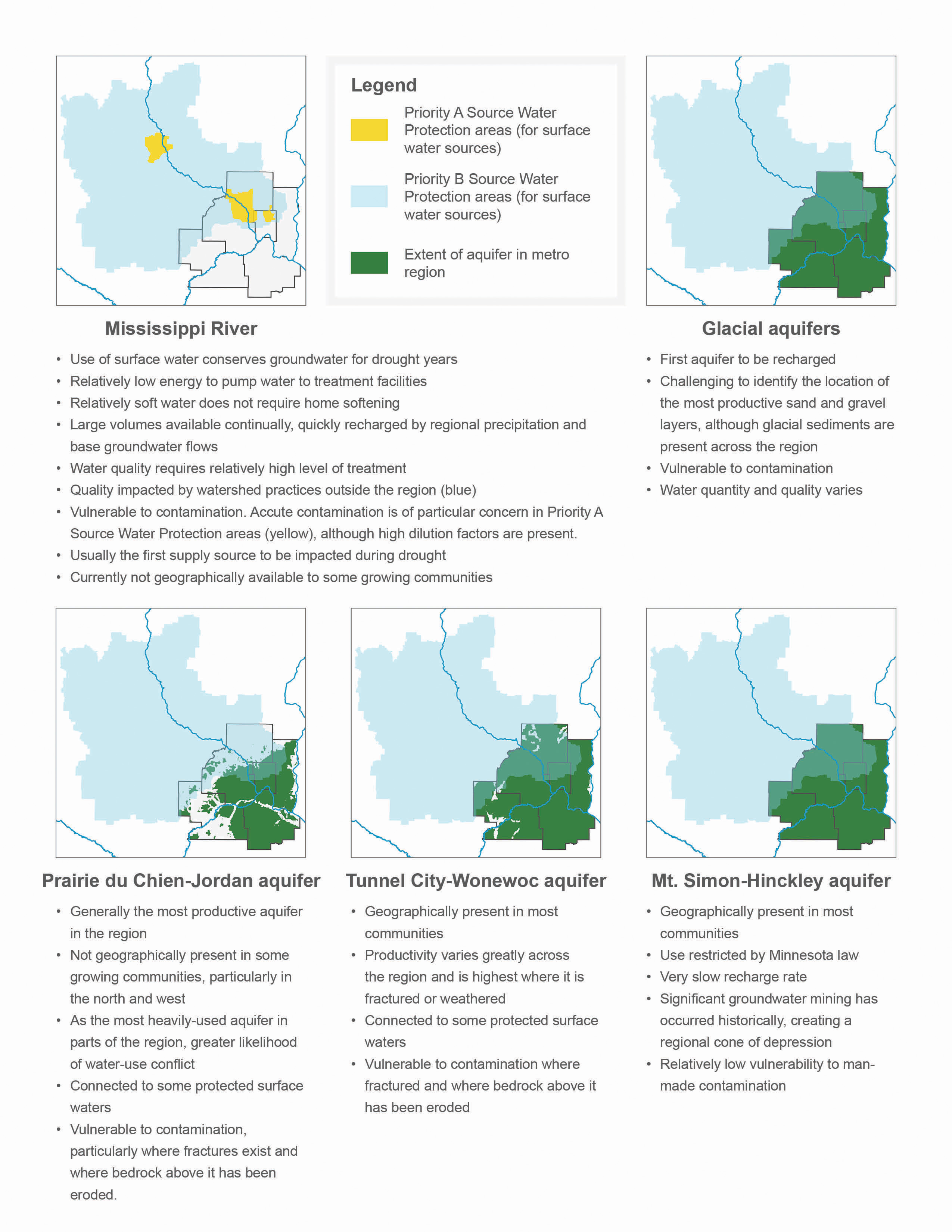

While the Twin Cities metro region is relatively water rich, not all sources of water are equally available, and each comes with its own management considerations. Figure 3.1 below illustrates the geographic extent of the region’s primary water supply sources and summarizes some of the benefits and challenges of each source.

Figure 3.1 Twin Cities region’s nonpower water sources. The region generally relies on the Mississippi River and four primary aquifers for non-power purposes, and each source has different management considerations.

Every community in the Twin Cities region gets at least part of its water supply from groundwater sources, through municipal and/or privately owned wells. However, a large portion of the region – almost a million people – also relies on surface water. Currently, the priority protection areas for municipal public water supply intakes on the Mississippi River (shown in yellow in Figure 3.1) are located partially or wholly within the communities of: Andover, Anoka, Arden Hills, Blaine, Brooklyn Center, Brooklyn Park, Centerville, Champlin, Columbia Heights, Coon Rapids, Crystal, Dayton, Fridley, Gem Lake, Ham Lake, Hilltop, Lino Lakes, Little Canada, Maple Grove, Minneapolis, Mounds View, New Brighton, New Hope, North Oaks, Osseo, Plymouth, Ramsey, Robbinsdale, Rogers, St. Anthony, Shoreview, Spring Lake Park, Vadnais Heights, White Bear Lake, and White Bear Township.

For the most up-to-date information about source water protection area delineations for groundwater and surface water sources, emergency response areas, and spill management areas, contact the Minnesota Department of Health.

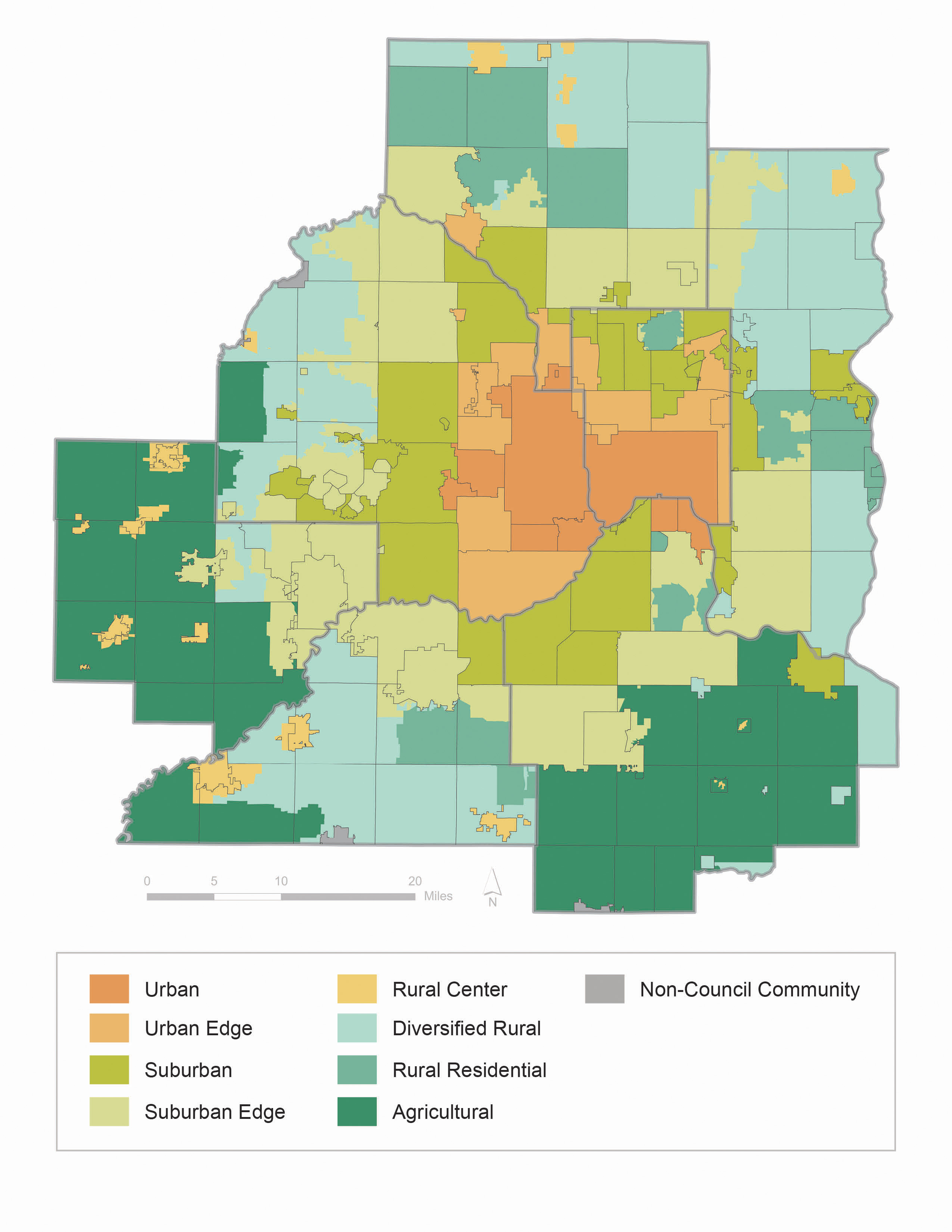

Water use patterns differ by community development type

A range of community types – with different land use characteristics, density expectations, and water supply needs – exist in the Twin Cities region. Some communities are highly urbanized, while others are agricultural and rural. Regional land use policies and supporting strategies, including those that connect to water supply priorities, are framed around these community designations (Figure 3.2).

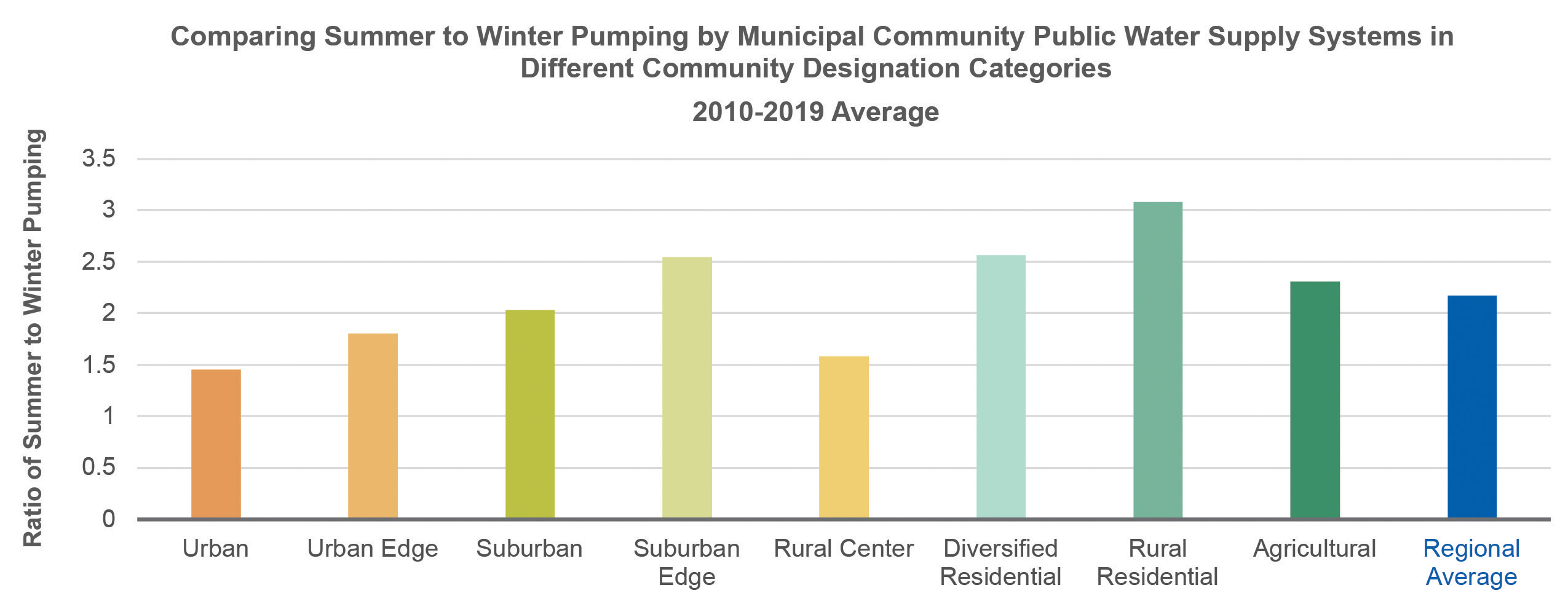

While community designations show similarities in land use, water-use patterns also vary among the different community designation types. Just one example of this is illustrated in Figure 3.3 – how summer versus winter water use varies by community designation. Local water supply-related plan updates should consider the community’s water use patterns as local controls are developed or updated to support water efficiency, emergency response, source-water protection, and other activities.

Figure 3.2: Imagine 2050 community designations

Data source: Met Council

Figure 3.3: Summer versus winter pumping from municipal community public water systems

Note: This graph does not include pumping by privately owned wells. Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ water permitting and reporting system, MPARS.

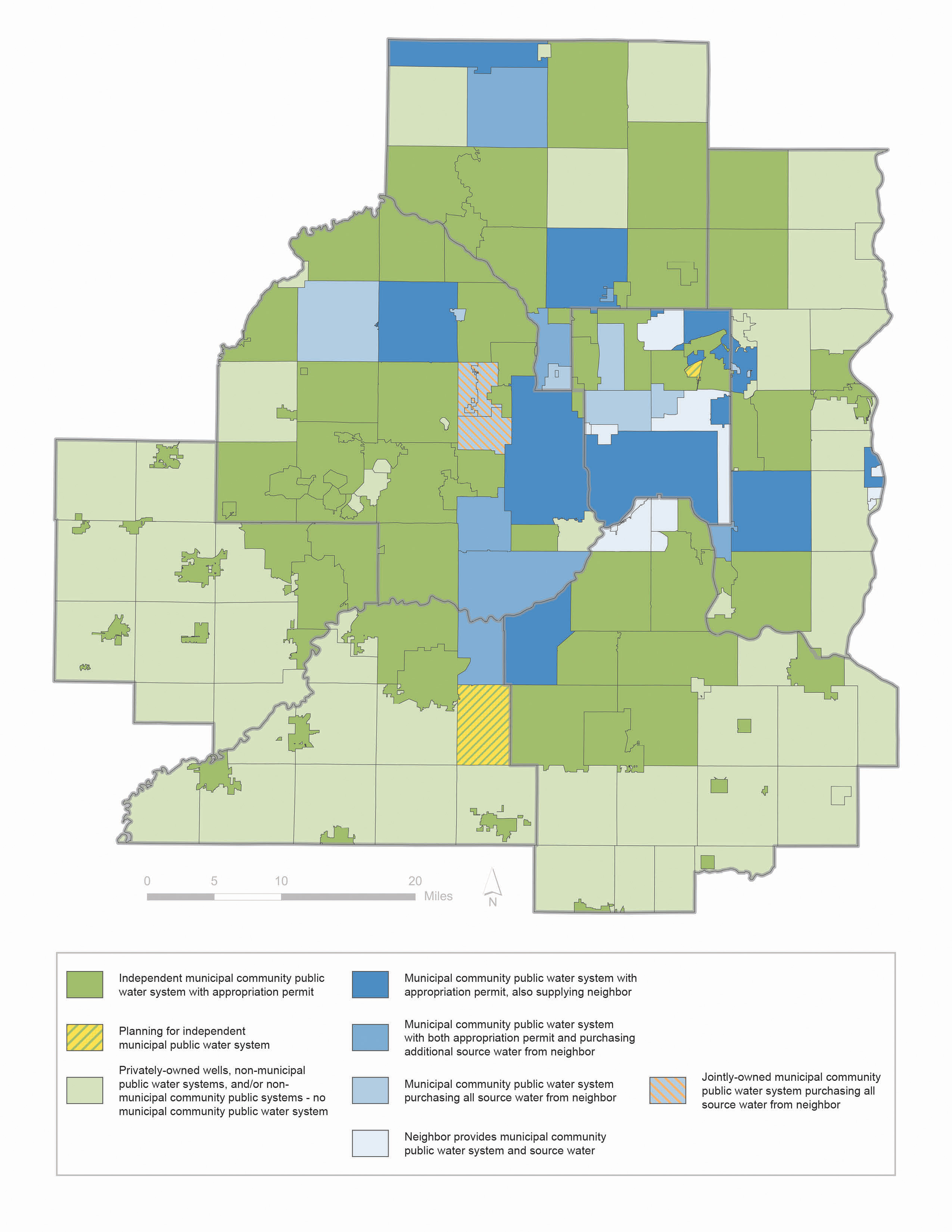

Type of water supply systems

Water supply conditions can still vary widely within community designation types (Figure 3.3). When planning for local water supply needs, it's important to understand the different water supply situations and planning requirements that communities in the metro region typically face.

For example, water supply planning requirements differ based on the type of water supply infrastructure serving the community. Some communities need to develop and implement local comprehensive plans, local water supply plans, and wellhead protection plans. Others develop local comprehensive plans and local water supply plans, but no wellhead protection plans. Still others only develop and implement local comprehensive plans. Table 3.1 summarizes some general categories of community water supply system types in the metro region, although each community has its own unique details. These categories are described in more detail below and in Figure 3.4. Appendix A provides more specific information about local water-supply-related plan requirements.

Table 3.1: Summary of community water supply system types in the Twin Cities metro region.

| Community water supply system type | Approximate number of communities | Approximate 2020 population | Approximate 2020-2050 population change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent municipal community public water system with appropriation permit | 84 | 1.5 million | +380,000 |

| Municipal community public water system with appropriation permit, also supplying neighbor(s) | 11 | 1 million | +190,000 |

| Municipal community public water system with both appropriation permit and purchasing additional source water from neighbor(s) | 7 | 200,000 | +40,000 |

| Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public systems - no municipal community public water system | 58 | 100,000 | +7,000 |

| Municipal community public water system purchasing all source water from neighbor(s) | 9 | 90,000 | +16,000 |

| Neighbor provides municipal community public water system and source | 12 | 90,000 | +9,000 |

| Jointly-owned municipal community public water supply system purchasing all source water from neighbor(s) | 3 | 70,000 | +7,000 |

| Planning for independent municipal community public water system | 2 | 6,000 | +600 |

Table includes the approximate number of communities in each category, approximate 2020 population, and approximate 2020-2050 population change.

- Independent municipal community public water system with appropriation permit (Example: Andover). People and businesses in these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems owned by their community. These communities have permits from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to pump water from local sources for their municipal community public supplies. Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems also provide water in these communities. All of these communities have land that has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area.

- Municipal community public water system with appropriation permit, also supplying neighbor(s) (Example: Minneapolis). People and businesses in these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems owned by their community. These communities have permits from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to pump water from local sources for their municipal community public supplies. Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems also provide water in these communities. In addition, these communities provide water to people and businesses in one or more neighboring communities. All of these communities have land that has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area.

- Municipal community public water system with both appropriation permit and purchasing additional source water from neighbor(s) (Example: Bloomington). People and businesses in these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems that are owned by their community. These communities have permits to pump water from local sources for their municipal community public supplies. The community also receives (buys) water from a neighboring water supply utility. In addition, privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems provide water in these communities. All of these communities have land that has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area.

- Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public systems - no municipal community public water system (Example: Afton): People and businesses in these communities can access water through privately owned wells or through nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems. Around 70% of these communities have land that has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area for one or more neighbors.

- Municipal community public water system purchasing all source water from neighbor(s) (Examples: Little Canada). People and businesses in these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems that are owned by their community. These communities receive (buy) water from a neighboring water supply utility for all of their municipal community public supply. Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems also provide water in these communities. All of these communities have land that has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area for one or more neighbors.

- Neighbor provides municipal community public water system and source water (Examples: Falcon Heights, North Oaks): People and businesses in parts or all of these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems that are owned by a neighboring public water supply system. These communities’ sources of water are the responsibility of neighboring water supply utilities, and customers receive a bill from that neighboring municipal community public water supply system. Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems also provide water in these communities. Most of these communities (85%) have land that's been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area for one or more neighbors.

- Jointly owned municipal community public water supply system purchasing all source water from neighbor(s) (Example: Crystal). People and businesses in parts or all of these communities can access water through municipal community public water supply systems that are jointly owned and operated by multiple communities. These communities receive (buy) water from a neighboring water supply utility for their shared public water supply system. These communities’ sources of water are the shared responsibility of the jointly owned water supply utility. Privately owned wells, nonmunicipal public water systems, and/or nonmunicipal community public water systems also provide water in these communities. All of these communities have land that’s been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area for one or more neighbors.

- Planning for independent municipal community public water system (Credit River, Gem Lake). People and businesses can access water through privately owned, noncommunity, and/or nonmunicipal wells alone, but the community is currently planning for a municipal community water supply system. Part of the community has been designated as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area for one or more neighbors.

Figure 3.4: Governance of water supply systems in the metro area varies from community to community

Data sources: MDH, DNR, and community local water supply plans and comprehensive plans

Given these eight different community designations, five different water sources, eight different water supply systems configurations, and the many other local differences, one size cannot fit all, and we benefit from taking a subregional approach. See the subregional chapters of this plan for more detail about those approaches.

Definition of success for water supply planning in the metro

Ensuring sustainable water supply for the region, now and in the future

This plan sets out to achieve a sustainable water supply for the entire region now and in the future.

Water supply is sustainable when its use does not harm ecosystems, degrade water quality and quantity, or compromise the ability of future generations to meet their water resource requirements.

The region’s water supply may be considered sustainable when:

- Water use does not exceed the estimated limits of available sources, taking into account:

- Impacts to aquifer levels (such as reducing water levels beyond the reach of public water supplies and privately owned wells),

- Impacts to surface waters and aquatic resources, including diversions of groundwater that affect flows and water levels, and

- Impacts to groundwater flow directions in areas where groundwater contamination has, or may, result in risks to public health.

- Planned land use and related water demand protects source waters and is consistent with long-term design capacity for water supply infrastructure, when that design capacity is based on sustainable sources.

- Individual water use supports sustainability, and appropriate mechanisms are in place to limit or forego nonessential water use during times of water shortage following natural disasters or other types of emergencies.

- Risk to infrastructure and public health is managed through ongoing assessment and investment.

This definition of water supply sustainability incorporates statutory descriptions of sustainability in Minnesota statutes, chapter 103G. Additionally, this definition goes beyond those statutory descriptions to more explicitly acknowledge infrastructure and land use, and is described in a way that can be translated into quantifiable terms that can be incorporated into technical analyses that support estimates of sustainable limits.

What success looks like

Stakeholders engaged in the update of this plan shared their hopes for the region’s water future – if we are successful, what does the region look like? This plan is grounded in those perspectives, shared through the Metro Area Water Supply Policy and Technical committees and through subregional water supply engagement in late 2023 and early 2024.

The following are descriptions of what success looks like, with related measures. As this plan is implemented, Met Council and partners will develop and track more specific targets.

- Water supply infrastructure. Public water suppliers can act quickly, be well informed about their decisions, and equitably address aging infrastructure, contamination, changing water availability, changing water demand, and financial challenges. Communities and their water supply are resilient to climate change and other impacts, because there is sufficient funding and other resources for water supply such as infrastructure, staff, new technology, etc. Measures of success may include:

-

- All communities have incorporated local controls to enhance water supply infrastructure resilience into local comprehensive planning and implementation.

- Water suppliers have identified and evaluated alternative sources as part of infrastructure resilience assessments.

- Public and privately owned water system owners collaborate more frequently with each other and agencies on asset management planning, emergency response, efficiency programs, source water protection, and other needs.

- Capital planning includes a minimum 10-year spending projections and factor in lifecycle estimates for major capital assets.

- Treatment and distribution infrastructure renewal is maintained with identified budgets and revenue sources.

-

- Water quality. Communities have the resources they need to provide clean, safe water for everyone. A shared process is developed that allows communities, water utilities, and regulators to understand and respond in a more coordinated and effective way to both contaminants of emerging concern and existing contamination. Measures of success may include:

-

- Water suppliers continue to meet water quality standards.

- Increased availability of funding for public water suppliers and privately owned well users to treat water to ensure high-quality water, including safe drinking water.

-

- Land use and water supply connections. Public water suppliers, land use planners, and developers have tools, funding and authority to work together – supported by aligned agency directions – so that growth is responsible and supported by reliable and adequate water supply. Development is done in ways that balance communities’ economic needs while protecting the quantity and quality of source waters that are vital to the region’s communities. A measure of success may include:

-

- Decision-makers consider water use as part of land use planning. For example, all communities have incorporated water efficiency and source water protection actions into their comprehensive plan updates and local implementation (development guidelines, etc.), so that water suppliers can support "more with less."

-

- Understand and manage groundwater and surface water interactions. Water resource managers, community planners, and leaders understand how groundwater and surface water interact and how those interactions impact water supply sustainability. Measures of success may include:

-

- Communities in the region understand where water-supply-related challenges from groundwater-surface water interaction take place.

- Groundwater and surface water source interactions across the region are adequately monitored with the data managed, shared, and used to inform impact analyses.

- There is an increase in the number of local controls adopted by communities to mitigate water-supply-related challenges posed by groundwater and surface water interactions.

-

- Sustainable water quantity. Communities and water agencies have a common understanding of the sustainable limits of groundwater and surface water sources and work together to collectively make plans that sustain an adequate supply – for people, the economy, and the function of local ecosystems. Agency directions are aligned and support local plans to safely supply demand that exceeds sustainable withdrawal rates using the most feasible combination of alternative groundwater or surface water sources, conservation, reclaimed wastewater and stormwater reuse. Measures of success may include:

-

-

- As a region, the average indoor, outdoor, and residential water use per person declines.

- As a region, the total summer versus winter water-use ratio declines.

- There is an increase in the number of water reuse installations and water efficiency improvements across all land use types (existing and new), leading to a corresponding decrease in drinking water use for nonessential purposes.

- The percentage of acres of new and redevelopment that incorporate turf grass alternatives increases.

-

Actions to support successful water supply planning

This action plan was developed in partnership with the Metro Area Water Supply Advisory Committee, its Technical Advisory Committee, and participants of a subregional water supply stakeholder engagement process. It is possible and expected that actions not reflected here may emerge in subsequent years. If so, this plan will be amended following the process described in Appendix A.

To achieve success, stakeholders identified the following as necessary conditions:

- All the voices are heard as community plans are made and implemented – so that the full range of diverse water supply needs are met.

- Public trust and understanding are enhanced, and a culture shift around water use has occurred.

- Collaborative and proactive approaches for engagement, planning, and plan implementation are taken within and across communities.

- The policy framework is streamlined and improved.

- State and regional support and funding for planning and plan implementation is increased.

Key steps for action

A regional framework for action (Figure 3.5) organizes work in a way to help achieve the desired outcomes for the region’s water supply. Some actions are most effective regionwide. However, some actions are more suited to certain parts of the region and are therefore described in more detail in the subregional chapters of the plan.

Figure 3.5: Metro region water supply framework for action

This figure illustrates the framework necessary to achieve Metro Area Water Supply Advisory Committee goals.

High-level schedule for different phases of work

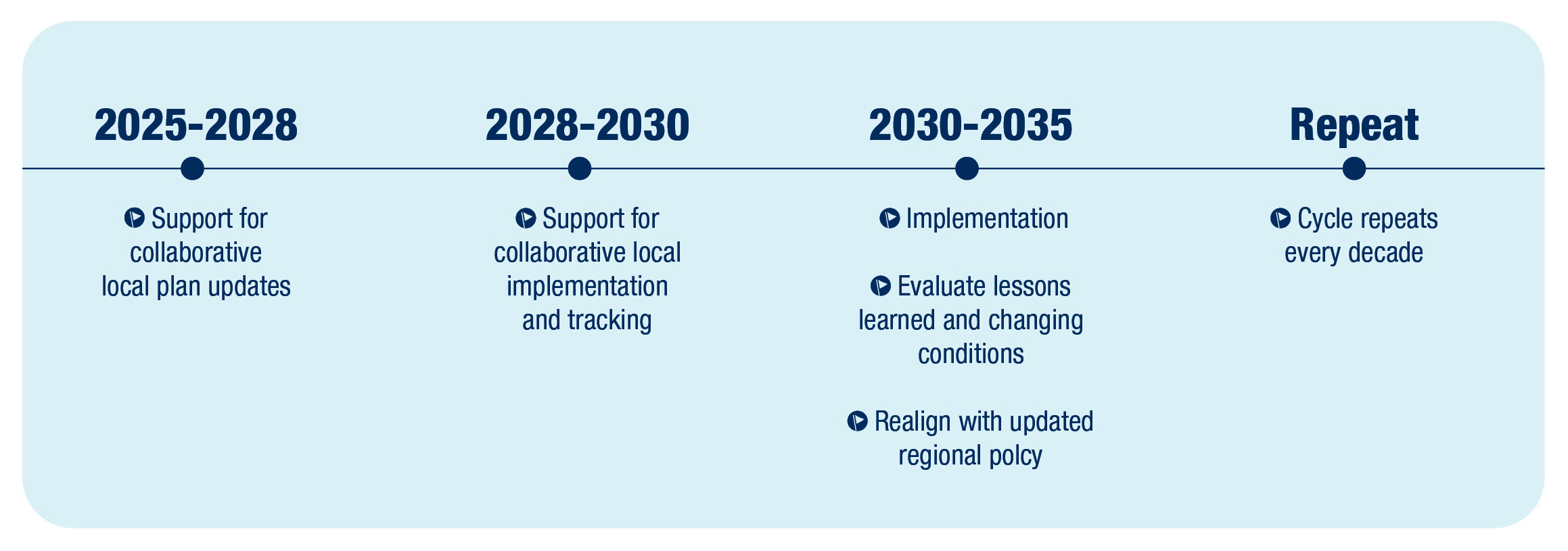

The following actions are expected to be ongoing, although the outputs are expected to shift through the region’s decennial planning process. For example, activities in 2025-2028 will focus more heavily on supporting local plan updates; activities in 2028-2030 will be more focused on supporting for local plan implementation; and work in 2030-2035 is expected to shift to program evaluation to inform regional policy and plan updates (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6: High-level schedule for different phases of water supply planning work

Table 3.2: Met Council commitments to regional water supply

| Regional water supply planning actions | Regional policy supporting this action |

|---|---|

| Collaboration and capacity building | |

|

Integrated water |

|

Integrated water |

|

Integrated water, reuse |

|

Integrated water, workforce |

|

Integrated water, reuse |

|

Integrated water, workforce, reuse, pollution prevention |

| 7. Met Council will seek resources and industry partners such as American Water Works Association and American Public Works Association, etc., to work with trades and workforce development organizations to create water sector career skill development opportunities and strengthen the water sector workforce talent pipeline, including water supply workforce. | Workforce |

| System assessment | |

|

8. Met Council will work with state and local partners to seek resources to include water supply risks in its monitoring, data, and assessment work. Priorities include:

|

Monitoring, data, and assessment; climate |

|

9. Met Council will work with partners to seek resources to describe, document, and diagram the region’s water supply system at a multi-community scale and in a way that acknowledges and respects water utility security needs. Priorities include:

|

Monitoring, data and assessment, |

| Mitigation measure evaluation | |

|

10. Met Council will work with partners to conduct technical studies to identify and evaluate existing and potential mitigation measures for priority water supply risks. Priorities include:

|

Monitoring, data and assessment, conservation |

| Planning and implementation | |

|

11. Met Council will center water supply planning as a key element as it convenes and supports ongoing subregional water planning. Priorities include:

|

Integrated water, conservation and sustainability |

|

12. Met Council will develop and provide technical assistance (guidance and incentives) to local partners to advance progress on implementation that supports municipal and nonmunicipal users and aligns with regional water supply priorities. Priorities include:

|

Integrated water, reuse, conservation and sustainability |

|

13. Met Council will collaborate with the state departments of natural resources and health to support local planning and implementation for municipal and nonmunicipal users that addresses high-priority water supply risks within each community and provides neighboring communities information to accurately assess and plan for their own risks. Priorities include:

|

Integrated water, conservation and sustainability |

|

14. Met Council will work with partners to advocate for increased state and federal funding to address impacts of water quality and quantity concerns on water supply infrastructure. Priorities include:

|

Conservation and sustainability |

|

15. Met Council will collaborate with state and local partners to develop, update, and implement emergency response planning linked to increased funding. Priorities include:

|

Conservation and sustainability, climate |

| 16. Met Council will develop, track, and report on regional and subregional indicators, targets, and performance measures. This information will be used to evaluate mitigation measures and continuously improve water supply planning, guided by the Metro Area Water Supply Advisory Committee, its Technical Advisory Committee, and subregional water supply groups. This may be regularly reported as a ‘State of the Region’s Water Supply’ summary or factsheet, which would support public review and update of this Metro Water Supply Plan more frequently than every 10 years and would support required updates to the Legislature and Met Council. | Monitoring, data and assessment |

Regional indicators and performance measures

Setting and tracking regional and subregional indicators and performance measures helps focus attention and resources on planned work and adapt to improve outcomes.

Regional indicators

Regional indicators are region-level measures that help provide context and build our shared understanding of past and current conditions.

Climate

Impacts from and community responses to climate-related water supply hazards such as flooding, drought, extreme heat, warming winters, and longer growing seasons.

Landscape (source areas)

Current and future land use and associated potential contaminants and water demand, particularly in Drinking Water Supply Management Areas.

Water supply sources

Source water quality, groundwater levels, river flow, ecosystems and water sensitive to changing groundwater levels, designation of areas as special well and boring construction areas; a summary of well interference/conflict reports, and trends in estimated volume of water being reused.

Water supply infrastructure

Metro-focused summaries of annual Minnesota Department of Health’s drinking water report results, Public Facility Authority’s estimated funding needs, American Society of Civil Engineers’ water supply infrastructure report card, and the number of privately owned wells drilled and sealed.

Water users/customers

Estimates of current and projected metro population (served and unserved); current and projected water use by category, season, indoor vs. outdoor, and source; and trends in per person water use. Note: If the region used an average of 80 gallons per person per day, 2050 growth could be supplied with the amount of water used regionally by municipal community public water supply systems in 2007 (the highest historic water use).

Wastewater and water resource recovery infrastructure

Impacts from development and redevelopment on indoor water use and related wastewater generation, wastewater flow trends, and water quality impacts of community use of water softeners.

Discharge to environment

Quality and quantity of waters receiving reclaimed wastewater.

Performance measures

Performance measures are information about Met Council operations, services, investments, programs, and policy objectives. These measures relate to what Met Council has more control over and help provide evidence of whether objectives’ targets are being reached.

- Subregional work group activity that includes collaboration on topics identified in regional and subregional action plans (examples: asset management planning, emergency response, efficiency programs, source water protection, and other needs)

- Established task forces with local stakeholders for the purpose of plan implementation

- Outreach and engagement materials available and used consistently across the region to increase awareness of sustainable water use, especially as the compounding effects of climate change contribute to fluctuating water availability. This is done in collaboration with organizations such as the Clean Water Council, Minnesota Ground Water Association, American Water Works – Minnesota Section, and others.

- Technical assistance provided to local planners (examples: number of wellhead protection plan and local water supply plan updates supported)

- Local plan updates that include:

- Adoption of local controls to enhance water supply infrastructure resilience.

- Alternative short- and long-term water sources in case of disruptions or limitations.

- Capital planning that includes a minimum 10-year spending projections and factor in lifecycle estimates for major capital assets.

- Financial resources for local partners (examples: grant funding, state appropriations)

- Impacts of water supply plan implementation projects and programs (example: gallons of water saved through efficiency grants)

Subregional water supply action plans

During and after the development of the 2015 Master Water Supply Plan, Met Council heard from stakeholders that “one size does not fit all,” and that future regional plans need to more fully reflect the differences across communities. In 2022, responding to that feedback, MAWSAC recommended that Met Council approach planning for the Metro Area Water Supply Plan from a subregional perspective. Met Council committed to supporting a robust subregional engagement approach for the 2025 Metro Area Water Supply Plan update.

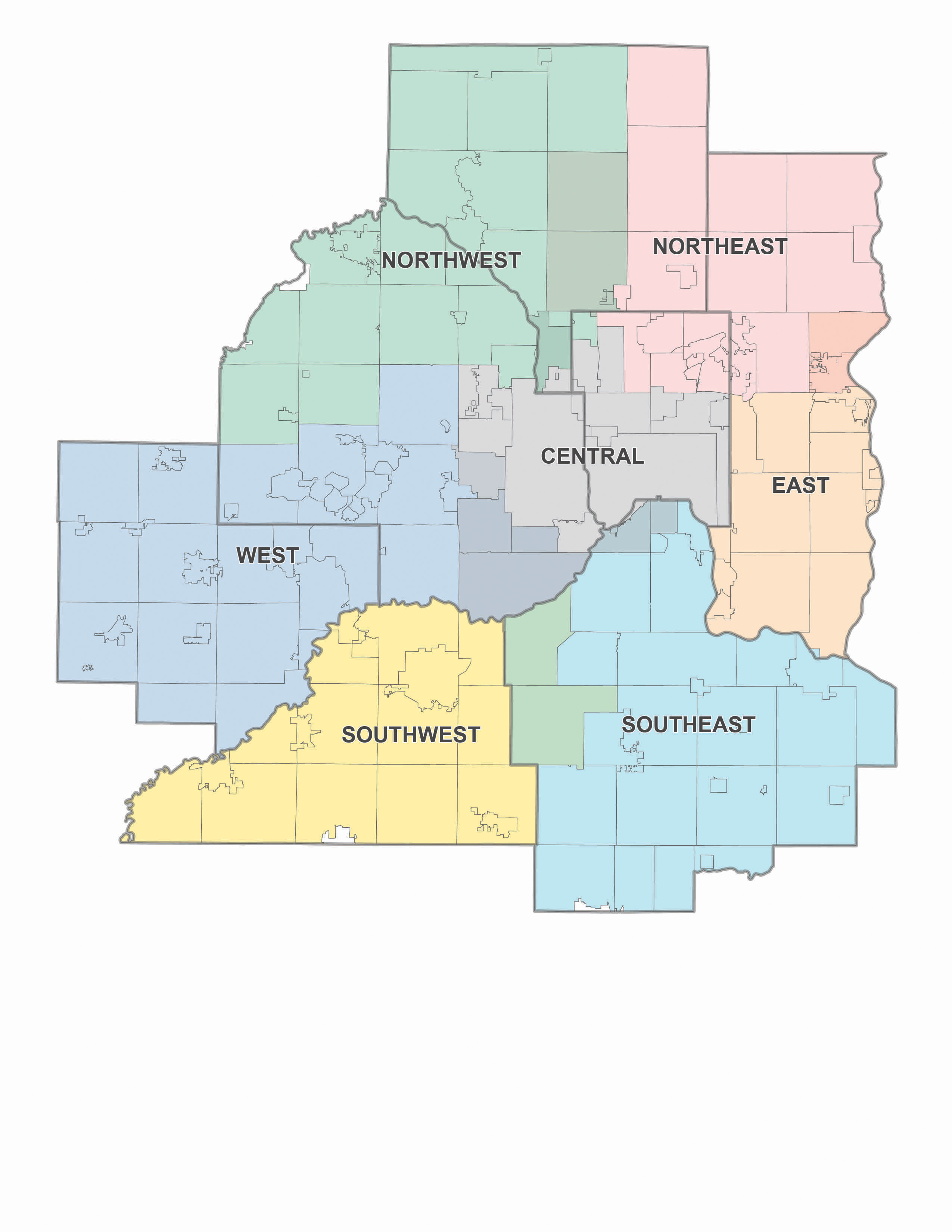

We took a subregional approach, reflected in the subregions identified in the Metropolitan Region Water Supply Planning Atlas as delineated in 2023. The subregions are neighboring communities connected by a combination of shared water challenges, hydrogeologic landscapes, and organically developed community water supply planning groups from previous planning cycles. As new information becomes available and community needs and relationship evolve, subregional boundaries may shift.

Figure 3.7: Subregional water supply planning areas

Data source: Water Supply Planning Atlas by the Met Council

Process to develop subregional action plan content

From March 2023 through February 2024, Met Council staff embarked on a highly participatory engagement campaign to approach planning from a subregional perspective. We used the subregional boundaries established through the development of the Water Supply Planning Atlas (Figure 3.7). The intent of this engagement was to:

- Integrate water supply, watershed, and land use planning perspectives.

- Build a shared vision for water supply in the subregion.

- Prioritize issues and opportunities.

- Develop an action plan to guide implementation.

- Enhance relationships within the subregion and with the Met Council.

We engaged with core teams of local leaders in each subregion in the summer of 2023 to collaboratively design how to engage their peers. Starting in the fall of 2023 and continuing through the winter of 2024, we hosted two to three workshops in each subregion to draft content in line with the intent described above.

Around 150 individuals participated in the seven-month process, representing 76 cities and townships and 44 nonmunicipal organizations. Perspectives included utility directors, watershed staff, community development planners, agency staff, nonprofits, large-volume water users, and more.

Participants expressed appreciation for the engagement work done to develop these chapters and requested that subregional engagement continue as a way to support focused implementation. The Met Council is committed to this continued engagement, as reflected in the regional commitments in the Metro Area Water Supply Plan and the rest of the 2050 Water Policy Plan.

Purpose and use of subregional action plans

The subregional water supply planning areas are primarily for the purpose of supporting collaboration, relationship building, and resource sharing across jurisdictional boundaries. They are not intended to add another layer of planning or to restrict local land use planning authority; rather, they are intended to support outreach and collaboration around existing planning efforts.

The Met Council respects and supports the responsibility and authority of local water suppliers in managing water resources while recognizing the importance of a cohesive regional perspective, as local water supply decisions impact neighboring communities. The Met Council’s role is to support regional water planning by delivering essential technical resources to guide sound decision-making and by offering planning assistance to local entities. As neither a water utility nor regulator, the Met Council’s water supply planning follows the Metro Area Water Supply Plan, cooperative framework that strengthens local control and accountability, developed in partnership with local, regional, and state stakeholders.

The outcomes from subregional engagement workgroups—often in their own words—are included in the subregional action plans in this section. These subregional action plans reflect the input given at the time of the engagement, with some minor revision during the process to adopt the Metro Area Water Supply Plan with the 2050 Water Policy Plan. While the plans as they stand will guide the Met Council’s water supply planning work in each of these subregions, many of the actions will be ones that subregional work groups take on themselves. These actions are expected to evolve over time as new issues and opportunities emerge.

Water supply planning context and current conditions

Everything that happens on land impacts water, and water is all connected.

The Central Metro subregion group (Figure 3.8) includes the cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, the communities served by those municipal community public water supply systems, and other surrounding communities. These communities are in the urban center of the region. This is the most highly developed part of the metro and the most densely populated.

The Central Metro subregion is unique among the seven subregions in that the Mississippi River is the primary drinking water source for most communities. Some communities, such as Bloomington, use a combination of groundwater and surface water to provide water, while others, such as New Brighton, rely primarily on groundwater, but may utilize a connection to the Minneapolis or the Saint Paul system during an emergency or as needs dictate. Some communities use groundwater as their only source of drinking water.

Few residents in this part of the metro receive their drinking water from privately owned domestic wells. However, there’s a greater concentration of wells for industrial or commercial purposes here than in other parts of the region. Additionally, 26 of the 27 communities in the Central Metro subregion overlap with or are adjacent to land that has been identified as a Drinking Water Supply Management Area.

With the region as a whole expected to grow by more than 650,000 people between 2020 and 2050, the Central metro subregion will continue to see growth. Current estimates suggest that approximately 200,000 more people will be added to the area by 2050 compared to 2020.

Over the past two decades, communities have continued to grow, but overall water use has generally declined since the late 1980s when water use peaked. However, density is likely to increase to accommodate estimated growth through development and redevelopment. To deliver service to more homes and businesses, communities may need new infrastructure to increase water supply, treatment, and storage capacities, and to expand water distribution systems.

Expansion of water supply systems comes at a cost and is not without financial, social, or environmental risk. To be sustainable, communities and the region must maximize current infrastructure investments and consider how growth, land use changes, climate impacts, inequity, and other challenges stress water resources and supply systems.

Beyond quantity, several quality-related items are also of concern in the Central Metro subregion:

- Increased impervious cover

- Source water protection (which requires collaboration with communities well beyond the seven-county metro planning region for surface-water-sourced communities)

- Legacy contamination

- Emerging contaminants such as PFAS and chloride

- Continued pursuit of water reuse

While management of water supply is ultimately a local responsibility, we know there is value in working together on water supply projects. Current partnerships are a testament to that. Water is all connected, and it does not follow jurisdictional boundaries—the work must acknowledge that as well.

Our water is facing threats from familiar and new contaminants including PFAS, nutrients, and chloride. We will support technical work/research to produce good information about water supplies so that our decision makers and the public can make timely, informed choices about actions that impact our shared water supplies.

The Central Metro chapter of the Water Supply Planning Atlas contains more details in the description of current challenges.

Stakeholder-defined vision of success for water supply planning in the Central Metro subregion

Water supply planning for the Central Metro subregion is successful if the following outcomes are produced or conditions are met in the long term:

- Regional collaboration supports information sharing, public education, and shared access to data such as source water quality and consumption.

- Strategies are implemented to optimize efficiency in operations.

- Regional growth planning considers sustainable source water availability.

- Reliability of infrastructure for anticipated growth is maximized through the implementation of asset management practices.

- Source water is protected through collaboration and enforcement efforts, and the region uses a diversity of source water.

- Adequate funding is available for water infrastructure.

- Public engagement is improved.

- Public health is a focus.

- Health guidance is provided for new contaminants.

- Lead is eliminated in homes, including water service lines, private home plumbing, and lead paint.

- The subregional plan is useful to communities with public water systems and privately owned wells for planning purposes.

- A culture shift occurs around nonessential water use, such as lawn irrigation, that changes behaviors.

- Water rates are affordable for customers.

- People understand that our drinking water is safe.

Issues and opportunities

Stakeholder engagement we conducted in the Central Metro subregion in 2023-2024 identified several issues and opportunities related to water supply planning. They are listed here in alphabetical order.

Agency coordination

Communication, data sharing, transparency, coordination, efficiency, and general partnership between and with agencies should be enhanced.

Asset management and investment

There is an overall lack of funding for water supply, including to maintain, grow, and expand infrastructure. Funding for water supply and asset management can be better coordinated and secured through many efforts including:

- Adoption of improved asset management strategies.

- Work to secure long-term funding for compliance issues.

- Leverage of existing funding sources.

- Have grants from different levels of government to support this work.

- Work with agencies to allow asset replacement related projects score higher on grant applications.

- A focus on infrastructure investment and sustainability.

- Engagement with and educate local elected officials on the importance of this work, and lobbying to secure funding.

Communication

Communication needs to be proactive, targeted, and tailored to specific audiences, and across platforms. At the same time, it needs to be coordinated and consistent.

Communication of scientific information needs to be relatable, and contain the “why,” “what,” and “how” to inspire both understanding and action at household and policy-making levels.

Increase the extent to which water supply is valued and prioritized by the public through intentional cultivation and strategic communications.

Data and technology

There is an overall lack of meaningful data for water suppliers, and the data that exists can be hard to find and access. A subregion-wide database for cities to share well and aquifer pumping data should be developed. Additionally, new technology is being developed, such as artificial intelligence, but is currently underutilized. The Central Metro subregion should utilize and explore how to incorporate new technology and tools in their work.

Education and engagement

Education and engagement are key to achieving success in all water supply work. Education and engagement efforts need to interact with diverse audiences including schools, politicians, the public, and public and private partners. Education and engagement should focus on:

- The importance of source water protection.

- Water quality and quantity.

- The cultural value of water.

- Water conservation and efficiency.

- Prevention is cheaper than remediation.

- Building trust in the safety of drinking water throughout the Central Metro subregion that is currently lacking due to cultural barriers and lack of trust in the government.

Planning

Water management strategies (stormwater, groundwater, surface water, land use, etc.) should be aligned to achieve effective planning and to help align goals and policies with their resources. Currently, stakeholders feel there are multiple competing priorities and poor prioritization. Additionally, the Central Metro subregion is the densest of the seven subregions and is expected to see an increase in population in the next 10 years. Growth affects water supply and sewer capacity, and questions on how best to handle this remain. Better planning in the Central Metro subregion could look like:

- Locals have more control and say in regional planning.

- A comprehensive plan is representative of the group needs.

- Regional growth is aligned to be more sustainable and water wise.

- Intercity wellhead protection plans and water supply plans are developed—common problems often have common solutions.

Water conservation and efficiency

Conservation and efficient water use support sustainable water supplies. Minnesota is projected to experience more drought events, and water suppliers must consider the ability of their water source(s) to meet higher water demands during such events. Education on conservation has been identified as a priority for the Central Metro subregion, specifically changing public ideas around lawns and irrigation and changing from traditional turfgrass to pollinator-friendly lawns and less water-intensive, more drought-tolerant turfgrass.

Additionally, conservation efforts need to be able to keep pace with increasing population, and an accepted balance of ground and surface water sources for the region should be considered. Plans and policies should encourage and incentivize redevelopment in the urban core, protecting important recharge areas outside the core.

Water quality

Existing contaminants need to be addressed before they enter groundwaters and surface waters. The region needs to prepare to respond to contaminants of emerging concern while working to reduce confusion and conflict between statutes and regulations. Currently, Central Metro subregion stakeholders feel that statutory regulations are evolving as the list of contaminants continues to expand. Additionally, they note experiencing the following constraints:

- As detection limits get lower and regulations get stricter, there needs to be an increase in funding to address them.

- It is difficult to stay abreast of evolving water quality regulations and standards due to increasing understanding of the risk of contaminants of concern.

- PFAS treatment and disposal costs need to be considered.

- As our knowledge of PFAS increases with evolving science, our understanding of its long-term health impacts is changing, which can lead to confusion among the public.

Workforce

Workforce concerns need to be addressed, including staffing shortages, lack of necessary funding for staff, turnover, and ability to attract and retain staff, and conversely, onboarding staff without enough mentors or supervisors.

Other focus areas for consideration

Finally, these focus areas were not heard during the Central Metro subregion’s first workshop but were heard across several other subregions and included for discussion at the Central Metro subregion’s second workshop.

- Reuse: Support use of reuse to reduce water demand.

- Chloride: Pursue limited liability legislation and support best practices to reduce chloride contamination from road salt and water softeners.

- Source water protection: Enhance source water and wellhead protection efforts for both known and emerging contaminants.

- Climate change: Climate change needs to be factored into future planning for water use as well as resilience to extremes and climate impacts.

Prioritized focus areas and action plan

As part of the engagement process, stakeholders identified the following priorities for the Central Metro subregion. Stakeholder-identified statements for what success looks like in 10 years are also included for each.

Affordability

- There will be equitable access to safe, affordable water for all.

- Terms like affordability will be defined.

- We will understand how to balance affordability with rates and act to do so.

- The general public understands the value of water.

Asset management and investment

- Assets will be in place to reliably service the needs of each community.

- Government will invest in additional assets to address changing standards.

- Assets will be planned for and replaced before end of life.

Data and technology

- There will be a central database for water system information, including water quality testing results, that is accessible to the public, regulatory agencies, and public water systems.

Education and engagement

- Communication will be coordinated in terms of content and actions between communities.

- There will be consistent messaging regarding source water protection, water quality, conservation water reuse (irrigation), cultural value of water, cultural barriers, lack of trust, and that contamination prevention is less costly than removal.

- Young people will speak intelligently about water, water use, water resources, etc., with continued levels of complexity so that they can shape future commentary. This should drive workforce as a secondary effect.

- Additionally, to help shape and influence belief in public water, community engagement needs to target lower-income areas and non-native Minnesotans that have moved to the state.

Planning

- Water availability, quality, and sustainability will be the first step to inform land use, development, population growth, transportation, etc.

- Built-out communities need to evaluate for capacity and growth and the ability to provide water to such growth with infrastructure expansion and redundancy.

- There will be more consistent guidance for contaminants of emerging concern so that the region can better plan for expanded future treatment.

Water conservation and efficiency

- We will move away from Kentucky bluegrass lawns.

- We will be maintaining current water consumption levels or minimizing rate of increase (per person).

- Rules that facilitate and promote water conservation and efficiency will be adjusted/implemented.

- Research to implement conservation and efficiency will be advanced – household level, community level, commercial, and industrial.

Water quality

- Water supplies will meet current and future health guidance standards.

- We will know how to prevent contaminants of emerging concern from entering water supply.

- There will be chemical reviews prior to use regarding disposal to water or soil discharge.

Workforce

- Utilities will be fully staffed.

- There will be skilled applicant pools.

- Workforce will be more representative of the communities served.

It should be noted that, as a part of the discussion, communication and agency coordination were identified as “implementation considerations” in that they would be needed (either as a strategy or something to manage for) to support success for any of the other focus areas. As such, these were requested to be incorporated into action plans to address priority focus areas.

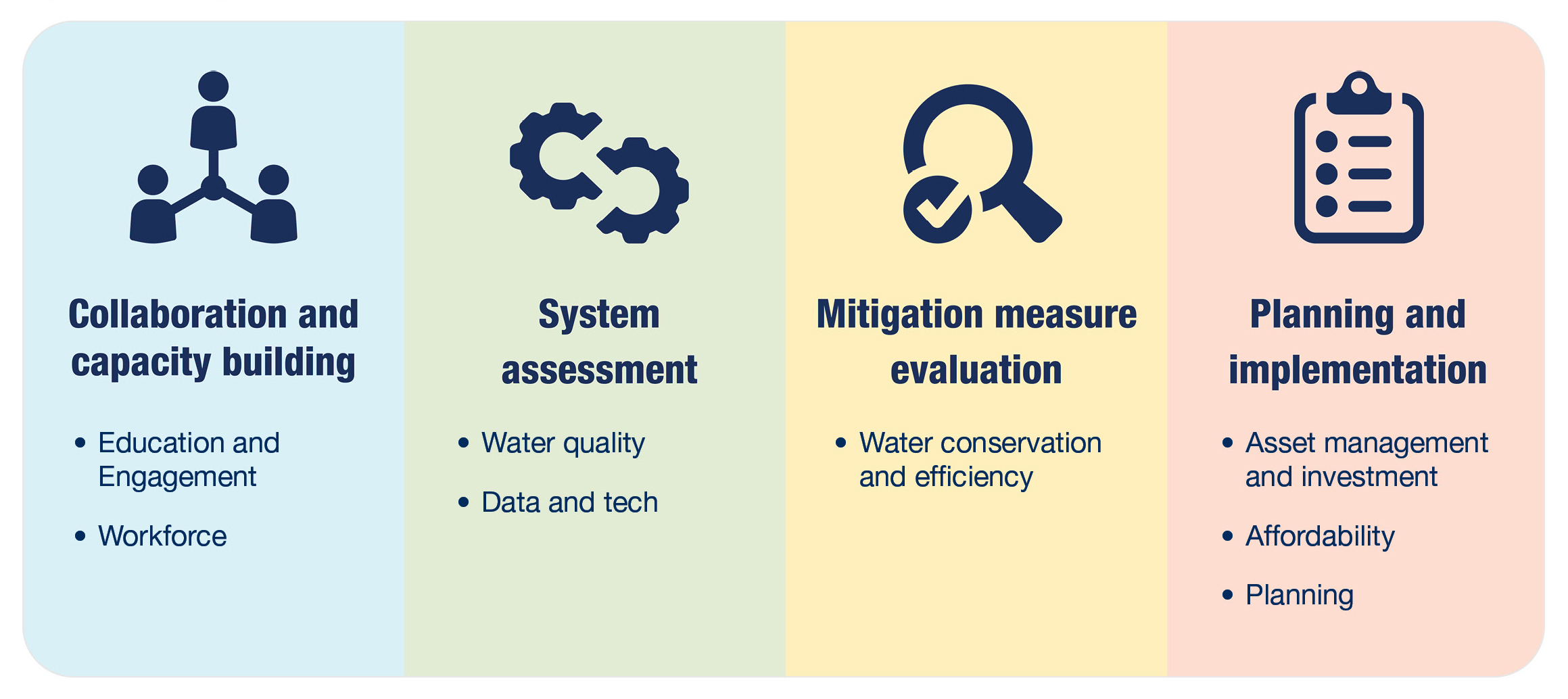

Table 3.3 reflects an action plan drafted by participants in a subregional water supply planning workshop series. We expect that actions not reflected here may emerge as important steps needed to be taken in subsequent years. This list, therefore, is a reflection of what was being considered in late 2023. The list has been organized according to the Metro Area Water Supply Advisory Committee’s 2022 proposed framework to achieve progress on regional goals (Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.9: Regional framework for action, with subregional detail

Actions to support success

In late 2023 and early 2024, Central Metro subregional stakeholders identified several potential actions to address each of their focus areas. Table 3.3 below includes proposed actions, in the words of the subregional stakeholders who drafted them. While the focus is on work needed over the next 10 years, some actions are expected to be ongoing over the next 25 years or more.

This action plan is intended as a high-level, long-term, collaborative planning tool. A refined work plan is expected to develop as collaboration gets underway and depending on resource availability. It is possible and expected that new actions may emerge as important steps that need to be taken in subsequent years.

Many different people and organizations are expected to be involved in the Central Metro subregional water supply work. Table 3.3 identifies a few examples that were identified by stakeholders in 2023 and 2024, but this list is incomplete.

The Met Council is committed to convene and support work planning and implementation for the Central Metro subregional water supply group (see the regional action plan in Table 3.2). Early work is expected to include revising and prioritizing actions and defining roles in more detail.

Table 3.3: Proposed Central Metro subregional water supply actions

| Proposed Action | Subregional Focus Area | Water Policy Plan Policy | 2025-2030 | 2030-2035 | 2035-2040 | 2040-2045 | 2045-2050 | Example Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLLABORATION AND CAPACITY BUILDING | ||||||||

| 1. Convene a communications committee with utility representatives that will explore different ways to connect and engage, including with diverse audiences and children. | Education & Engagement | Conservation & Sustainability, Integrated Water | X | X | Met Council and local governments | |||

| 2. Perform outreach and engagement with the public through community groups, attending festivals, etc. | Education & Engagement | Conservation & Sustainability, Integrated Water | Met Council, local governments, state agencies, counties, community organizations | |||||

| 3. Education campaign to shift public perception that MN has unlimited supply of water. | Education, Planning | Conservation & Sustainability | X | Regional agencies | ||||

| 4. Education campaign on what affordability is and how to overcome barriers. | Education, Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | |||||

| 5. Create and implement education and engagement for diverse audiences around actions they can take to conserve water and why. | Education, Water Conservation & Efficiency | Conservation & Sustainability | X | K-12 schools, colleges, and state agencies | ||||

| 6. Grow partnerships with technical schools and Tribal colleges to increase education-based programs like WETT and WUTT (Water Utility Treatment and Technology program, from the American Public Works Association in relationship with Saint Paul College). | Education, Workforce | Water Sector Workforce | ||||||

| 7. Increase outreach to high schools, and the public about jobs in the field through outreach at job fairs, tech schools, and encouraging schools to offer trade classes. | Education, Workforce | Water Sector Workforce | X | Utilities and Met Council, Engineering associations, state agencies, and cities | ||||

| 8. Offer site visits to water treatment plants for community college students. | Education, Workforce | Water Sector Workforce | Cities and agencies with facilities | |||||

| 9. Utilize internships and similar programs to jumpstart careers in the industry at a younger age. | Workforce | Water Sector Workforce | Utilities | |||||

| SYSTEM ASSESSMENT | ||||||||

| 10. The state agencies convene a team to create a database clearinghouse that houses water quality data, provides management and analysis, and the ability to transfer data for stakeholder analysis. | Data & Technology | Monitoring/Data/ Assessment | X | MDH, MPCA, DNR, MNIT | ||||

| 11. Continue to convene subregion to work with state agencies on creation of data clearinghouse and the prioritization of tech improvements. | Data & Technology | Monitoring/Data/ Assessment | X | X | Public water supplies Agency commissioners |

|||

| 12. Research water treatment methods that have a high confidence to handle unknown, emerging contaminants, then identify and prioritize most-at-risk communities. | Water Quality, Planning | Pollution Prevention | X | MDH | ||||

| 13. Conduct proactive sampling and health studies for contaminants of emerging concern. | Water Quality | Pollution Prevention | X | MDH | ||||

| 14. Create a program for surveillance and testing of new contaminants in drinking water and wastewater. | Water Quality | Pollution Prevention | X | |||||

| 15. Increase upstream water quality monitoring for surface water intakes. | Water Quality | Pollution Prevention | X | MDH, MPCA, Watersheds, USGS | ||||

| 16. Creation of policies and leverage of funding to reduce nonpoint-source pollution and contamination. | Water Quality | Pollution Prevention | MPCA, MDA, and Met Council | |||||

| 17. Identify best available technologies and provide region-specific life cycle cost estimates for new treatment technologies to handle emerging contaminants. | Water Quality | Conservation & Sustainability, Pollution Prevention | X | MDH and suppliers | ||||

| 18. Perform a review of infiltration requirements and change if needed to provide better protection. |

Water Quality, Planning | Integrated Water Management | X | MPCA, MCES, DNR, and MDH | ||||

| MITIGATION MEASURE EVALUATION | ||||||||

| 19. Collect water supply data to inform our current state and to help inform what will be feasible in the next 10, 20 years, and beyond. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Monitoring/Data/ Assessment | X | Water utilities, water users, state agencies, and academia | ||||

| 20. Work with state agencies to advocate for reuse and to limit the barriers to implementation. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Reuse | X | |||||

| 21. Create different actions and priorities for irrigation and personal/household use. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Conservation & Sustainability | X | X | DNR MDH |

|||

| 22. Pass ordinances to mandate low-flow appliances in new developments. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Conservation & Sustainability | X | Cities and state agencies | ||||

| 23. Met Council to continue providing water efficiency grants. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Conservation & Sustainability | X | X | Met Council and MPCA | |||

| 24. Pass ordinances to require native and drought-tolerant landscaping on new and re-development. | Water Conservation & Efficiency | Conservation & Sustainability | X | Cities and state agencies | ||||

| PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION | ||||||||

| 25. Collaborate on the development and completion of a multi-community wellhead protection plan update and implementation process. | Planning | Planning | X | X | Cities, MDH, watersheds | |||

| 26. Work to leverage and make funds available to make necessary upgrades, improvements, and replacements. | Asset Management & Investment, Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | Cities | ||||

| 27. Create education tools to engage decisions makers and the community on asset management, | Asset Management & Investment, Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | City engineers/public works directors | ||||

| 28. Support asset replacement planning/CIPs to project expenditures and likely rate changes. | Asset Management & Investment, Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | City councils | ||||

| 29. Convene a team to standardize asset management platforms – identifying needs, deficiencies, and high-risk assets. | Asset Management & Investment, Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | MDH and MPCA | ||||

| 30. Work with Met Council to create growth and land use policy that is supported by infrastructure, water supply, and wastewater treatment capacity. | Planning | Integrated Water | X | X | Met Council, local governments, and DNR |

|||

| 31. Work with the legislature to take pressure off of the metro area to grow by encouraging growth in regional centers: Mankato, Moorhead, Duluth, Rochester, Worthington, etc. This may include sharing information about the limitations of the metro region’s water supplies with the State of Minnesota’s economic development groups, to support strategic planning decisions. | Planning | State – Legislature planning | ||||||

| 32. Met Council integrate water resource planning into local planning assistance decision-making. | Planning | Integrated Water | X | Met Council and DNR | ||||

| 33. Convene the subregion and define what affordability means, identify barriers to achieving affordability and how to overcome them. | Affordability | Conservation & Sustainability | X | X | Met Council | |||

| 34. Work to identify and leverage a source of funding to help water producers negotiate the changing regulations. | Affordability, Water Quality | Conservation & Sustainability, Pollution Prevention | X | State agencies/EPA/Met Council | ||||

| 35. Incorporate review of groundwater impacts into stormwater management design and develop guidance for how stormwater practices impact groundwater. | Water Quality, Planning | Integrated Water | X | MPCA, Met Council, MDH, and watersheds | ||||

| 36. Work with state and locals to strengthen protections for surface source water. | Water Quality, Planning | Pollution Prevention | X | MPCA and Met Council | ||||

| 37. Prioritize water treatment systems that need new or modified systems for funding. | Water Quality, Affordability, Asset Management | Pollution Prevention | X | MDH | ||||